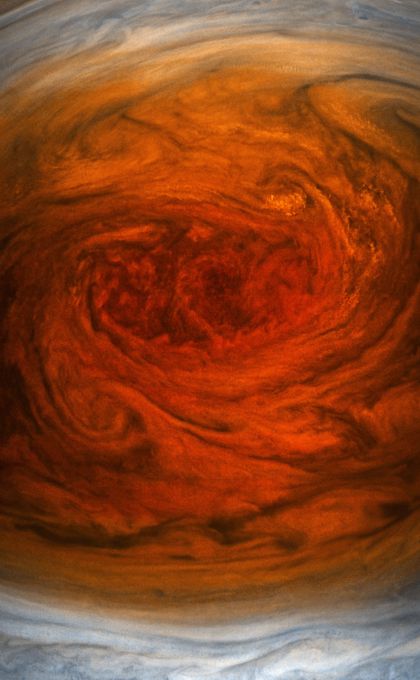

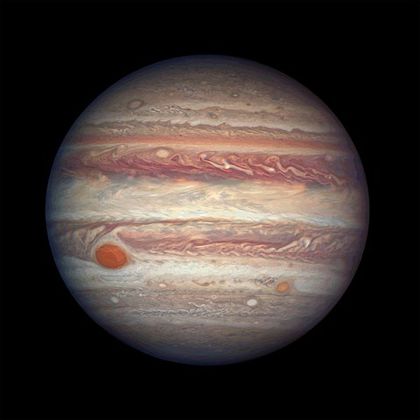

Cal (formerly known as Al) comes over to our table in his coffee shop. “Lessee if I got this right. Cathleen is smug twice. First time because the new results from Juno‘s data say her hunch is right that Jupiter’s atmosphere moves like cylinders inside each other. Nearly cylinders, anyhow. Second smug because Sy used the Juno data to draw a math picture he says shows the Great Red Spot but I’m lookin’ at it and I don’t see how your wiggle‑waggles show a Spot. That’s a weird map, so why’re you smug about it, Cathleen?”

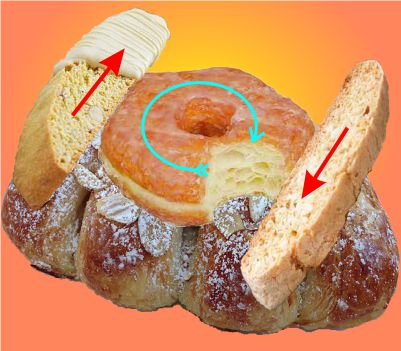

“The map’s weird because it’s abstract and way different from the maps you’re used to. It’s also weird because of how the data was collected. Sy, you tell him about the arcs.”

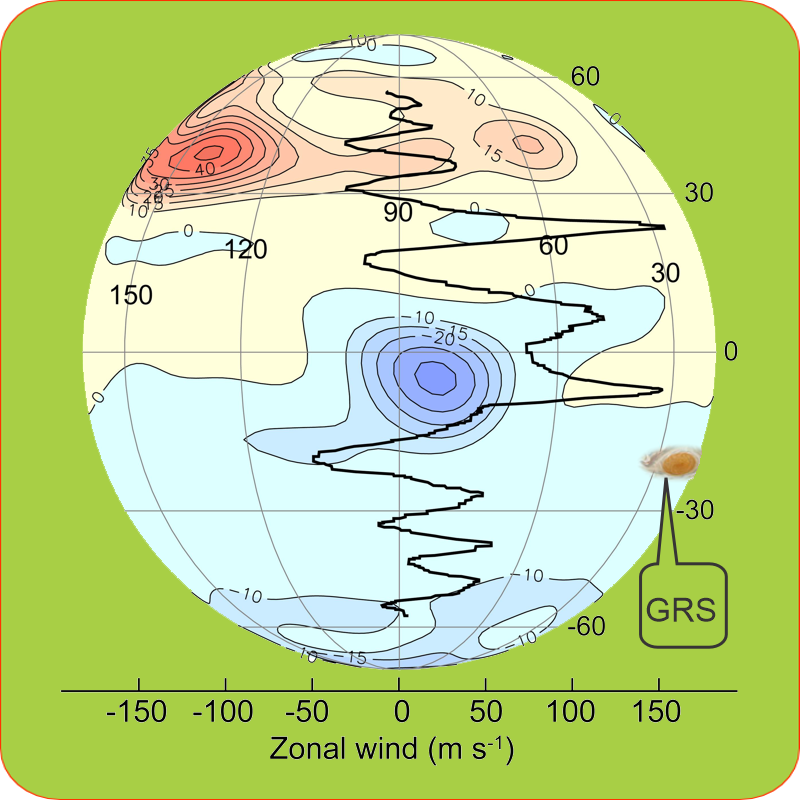

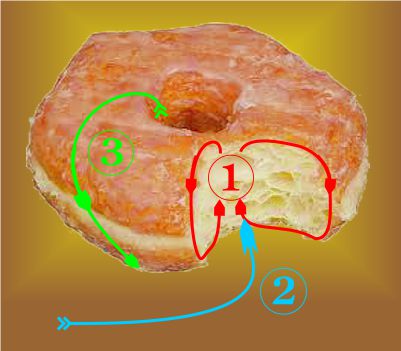

“Okay. Umm… Cal, the maps you’re familiar with are two‑dimensional. City maps show you north‑south and east‑west, that’s one dimension for each direction pair. Maps for bigger‑scale territories use latitude for north‑south and longitude for east‑west but the principle’s the same. The Kaspi group’s calculations from Juno‘s orbit data give us a recipe for only a one‑dimensional map. They show how Jupiter’s gravity varies by latitude, nothing about longitude. We could plot that as a rectangle, latitude along the x‑axis, relative strength along the y‑axis. I thought I’d learn more by wrapping the x‑axis around the planet so we could look for correlations with Jupiter’s geography. I found something and that’s why Cathleen’s smug. Me, too.”

“Why latitude but nothing about longitude?”

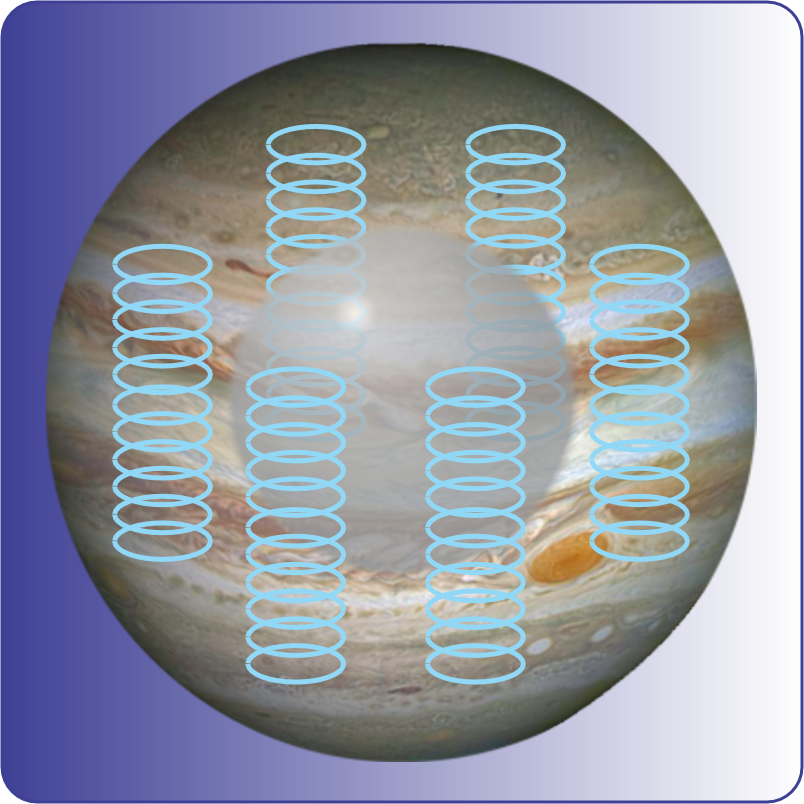

“Because of the way Juno‘s orbit works. The spacecraft’s not hovering over the planet or even circling it like the ISS circles Earth. NASA wanted to minimize Juno‘s exposure to Jupiter’s intense magnetic and radiation fields. The craft spends most of its 53‑day orbit at extreme distance, up to millions of kilometers out. When it approaches, it screams in at about 41 kilometers per second, that’s 91 700 mph, on a mostly north‑to‑south vector so it sees all latitudes from a few thousand kilometers above the cloud‑tops. Close approach lasts only about three hours, for the whole planet, and then the thing is on its way out again. During that three hours, the planet rotates about 120° underneath Juno so we don’t have a straight vertical N‑S pass down the planet’s face. Gathering useful longitude data’s going to take a lot more orbits.”

“So you’re sayin’ Juno felt gravity glitches at all different angles going pole to pole, but only some of the angles going round and round.”

“Exactly.”

“So now explain the wiggle‑waggles.”

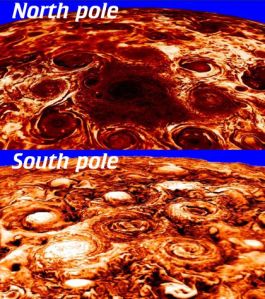

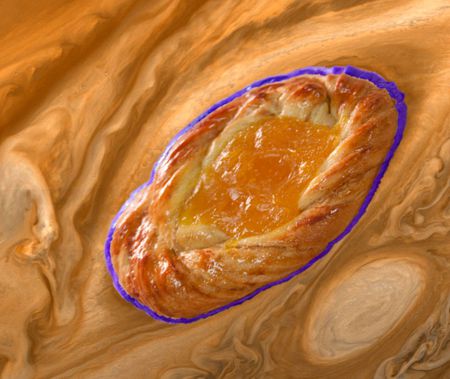

“They represent parts‑per‑million variations in the field pulling Juno towards Jupiter at each latitude. Where the craft is over a more massive region it’s pulled a bit inwards and Sy’s map shows that as a green bump. Over a lighter region Juno‘s free to move outward a little and the map shows a pink dip. Kaspi and company interpret the heaviness just north of the equator to be a dense inward flow of gas all around the planet. Maybe it is. Sy and I think the pink droplet south of the equator could reflect the Great Red Spot lowering the average mass at its latitude. Maybe it is. As always, we need more data, okay? Now I’ve got questions for you, Sy.”

“Shoot.”

“You built your map by multiplying each Jn‑shape by its Kaspi gravitational intensity then adding the multiplied shapes together. But you only used Jn‑shapes with integer names. Is there a J½?”

“Some mathematicians play with fractional J‑thingies but I’ve not followed that topic.”

“Understandable. Next question — the J‘s look so much like sine waves. Why not just use sine‑shapes?”

“I used Jn‑shapes because that’s how Kaspi’s group stated their results. They had no choice in the matter. Jn‑shapes naturally appear in spherical system math. The nice thing about Jn‑shapes is that n provides a sort of wavelength scale. For instance, J35 divides Jupiter’s pole‑to‑pole arc into 36 segments each as wide as Earth’s diameter. Here’s a plot of intensity against n.”

“Left to right, red light to blue.”

“Exactly.”

~ Rich Olcott