“Uh, Mr Moire? Would you mind if we used Old Reliable to do the calculations on this problem about the galaxy cluster’s Virial?”

“Mm, only if you direct the computation, Jeremy. I want to be able to face Professor Hanneken with a clear conscience if your name ever comes up in the conversation. Where do we start?”

“With the data he printed here on the other side of the problem sheet. Old Reliable can scan it in, right?”

“Certainly. What are the columns?”

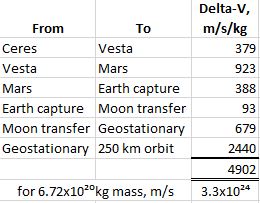

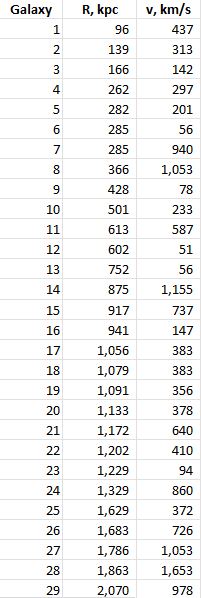

“The first one’s clear. The second column is the distance between the galaxy and the center of the cluster. Professor Hanneken said the published data was in degrees but he converted that to kiloparsecs to get past a complication of some sort. The third column is, umm, ‘the relative line‑of‑sight velocity.’ I understand the line‑of‑sight part, but the numbers don’t look relativistic.”

“You’re right, they’re much smaller than lightspeed’s 300,000 km/s. I’m sure the author was referring to each galaxy’s motion relative to the other ones. That’s what the Virial’s about, after all. I’ll bet John also subtracted the cluster’s average velocity from each of the measured values because we don’t care about how the galaxies move relative to us. Okay, we’ve scanned your data. What do we do next?”

“Chart it, please, in a scatter plot. That’s always the first thing I do.”

“Wise choice. Here you go. What do we learn from this?”

“On the whole it looks pretty flat. Both fast and slow speeds are spread across the whole cluster. If the whole cluster’s rotating we’d see faster galaxies near the center but we don’t. They’re all moving randomly so the Virial idea should apply, right?”

“Mm-hm. Does it bother you that we’re only looking at motion towards or away from us?”

“Uhh, I hadn’t thought about that. You’re right, galaxy movements across the sky would be way too slow for us to detect. I guess the slowest ones here could actually be moving as fast as the others but they’re going crosswise. How do we correct for that?”

“Won’t need much adjustment. The measured numbers probably skew low but the average should be correct within a factor of 2. What’s next?”

“Let’s do the kinetic energy piece T. That’d be the average of galaxy mass m times v²/2 for each galaxy. But we don’t know the masses. For that matter, the potential energy piece, V=G·M·m/R, also needs galaxy mass.”

“If you divide each piece by m you get specific energy, joules/kilogram of galaxy. That’s the same as (km/s)². Does that help?”

“Cool. So have Old Reliable calculate v²/2 for each galaxy, then take the average.”

“We get 208,448 J/kg, which is too many significant figures but never mind. Now what?”

“Twice T would be 416,896 which the Virial Theorem says equals the specific potential energy. That’d be Newton’s G times the cluster mass M divided by the average distance R. Wait, we don’t know M but we do know everything else so we can find M. And dividing that by the galaxy count would be average mass per galaxy. So take the average of all the R distances, times the 416,896 number, and divide that by G.”

“What units do you want G in?”

“Mmm… To cancel the units right we need J/kg times parsecs over … can we do solar masses? That’d be easier to think about than kilograms.”

“Old Reliable says G = 4.3×10-3 (J/kg)·pc/Mʘ. Also, the average R is … 890,751 parsecs. Calculating M=v²·R/G … says M is about 90 trillion solar masses. With 29 galaxies the average is around 3 trillion solar masses give or take a couple of factors of 2 or so.”

“But that’s a crazy number, Mr Moire. The Milky Way only has 100 billion stars.”

“Sometimes when the numbers are crazy, we’ve done something wrong. Sometimes the numbers tell us something. These numbers mutter ‘dark matter‘ but in the 1930s only Fritz Zwicky was listening.”

~~ Rich Olcott

- Thanks again to Dr KaChun Yu for pointing out Sinclair Smith’s 1936 paper. Naturally, any errors in this post are my own.