“‘That’s where the argument started‘? That’s right up there with ‘Then the murders began.’ Cathleen Cliff‑hanger strikes again.”

<giggling> “Gotcha, Sy, just like always. Sorry, Kareem, we’ve had this thing since we were kids.”

“Don’t mind me, but do tell him what’s awry with the top of your galactic distance ladder.”

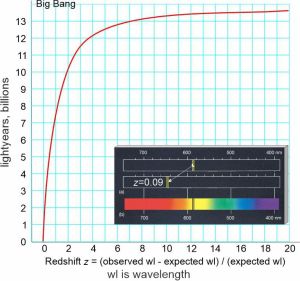

“I need to fill you in first about the ladder’s framework. We know the distances to special ‘standard candles’ scattered across the Universe, but there’s oodles of other objects that aren’t special that way. We can’t know their distances unless we can tie them to the candles somehow. Distance was Edwin Hubble’s big thing. Twenty years after Henrietta Swan Leavitt identified one kind of candle, Hubble studied the light from them. The farthest spectra were stretched more than the closest ones. Better yet, there was a strict relationship between the amount of stretch, we call it the z factor, and the candle’s distance. Turns out that everything at the intergalactic scale is getting farther from everything else. He didn’t call that expansion the Hubble Flow but we do. It comes to about 7% per billion lightyears distance. z connects candle spectrum, object spectrum and object distance. That lets us calibrate successive overlapping steps on the distance ladder, one candle type to the next one.”

“A constant growth rate — that’s exponential, by definition. Like compound interest. The higher it gets, it gets even higher faster.”

“Right, Kareem, except that in the past quarter-century we’ve realized that Hubble was an optimist. The latest data suggests the expansion he discovered is accelerating. We don’t know why but dark energy might have something to do with it. But that’s another story.”

“Cathleen, you said the distance ladder’s top rung had something to do with surface brightness. Surface of what?”

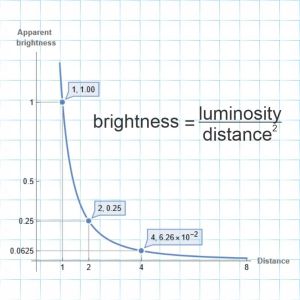

“Galaxies. Stars come at all levels of brightness. You can confirm that visually, at least if you’re in a good dark‑sky area. But a galaxy has billions of stars. When we assess brightness for a galaxy as a whole, the brightest stars make up for the dimmest ones. On the average it’ll look like a bunch of average stars. The idea is that the apparent brightness of some galaxy tells you roughly how many average stars it holds. In turn, that gives you a rough estimate of the galaxy’s mass — our final step up the mass ladder. Well, except for gravitational lensing, but that’s another story.”

“So what’s wrong with that candle?”

“We didn’t think anything was wrong until recently. Do you remember that spate of popular science news stories a year ago about giant galaxies near the beginning of time when they had no business to exist yet?”

“Yeah, there was a lot of noise about we’ll have to revise our theories about how the Universe evolved from the Big Bang, but the articles I saw didn’t have much detail. From what you’ve said so far, let me guess. These were new galaxy sightings, so probably from James Webb Space Telescope data. JWST is good at infra‑red so they must have been looking at severely stretched starlight—”

“z-factor near 8″

“— so near 13 billion lightyears old, but the ‘surface brightness’ standard candle led the researchers to claim their galaxies held some ridiculous number of stars for that era, at least according to current theory. How’d I do?”

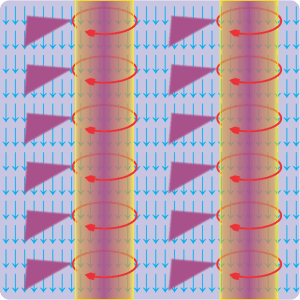

“Good guess, Sy. That’s where things stood for almost a year until scientists did what scientists do. A different research group looking at even more data as part of a larger project came up with a simpler explanation. Using additional data from JWST and several other sources, the group concentrated on the most massive galaxies, starting with low‑z recent ones and working back to z=9. Along the way they found some EROs — Extremely Red Objects where a blast of infra‑red boosts their normal starlight brightness. The researchers attribute the blast to hot dust associated with a super‑massive black hole at each ERO’s center. The blast makes an ERO appear more massive than it really is. Guess what? The first report’s ‘ridiculously massive’ early galaxies were EROs. Can’t have them in that top rung.”

“Kareem, how about the rungs on your ladder?”

~~ Rich Olcott