Mid-afternoon, time for a coffee break. As I enter Cal’s shop, I see Cathleen and Kareem chuckling together behind a jumble of Cal’s distinctive graph‑lined paper napkins. “What’s the topic of conversation, guys?”

“Hi, Sy. Kareem and I are comparing ladders.”

I look around, don’t see anything that looks like construction equipment.

“Not that kind, Sy. What’s your definition of a ladder?”

“Getting down to definitions, eh, Kareem? Okay, it’s a framework with steps you can climb up towards something you can’t reach.”

“Well, there you go.”

“Not much help, Cathleen. What are you really bantering about?”

“Each of our fields of study has a framework with steps that let us measure something that’d be way out of reach without it.”

“You’ll appreciate this, Sy — our ladders even use different math. The steps on Cathleen’s ladder are mostly linear, mine are mostly exponential.”

“And they’re both finicky — you have to be really careful when using them.”

“And they’ve both recently had adjustments at the top end.”

“I can see the fun, I think. How about some specifics?”

They exchange a look, Kareem gestures ‘after you‘ and Cathleen opens. “Mine’s in astrometry, Sy, the precise recording of relative positions. Tycho Brahe’s numbers were good to a few dozen arcseconds—”

“Arcsecond?”

“1/60 of an arcminute which is 1/60 of a degree which is 1/360 of a full circle around the sky. Good enough in Newton’s day for him to explain planetary orbits, but we’ve come <ahem> a long way since then. The Gaia telescope mission can resolve certain objects down to a few microarcseconds but that’s only half the problem.”

“Let me guess — you have angles but you don’t have distances.”

“Bingo. Distance is astrometry’s biggest challenge.”

“Wait, Newton’s Law of Gravity includes r as the distance between objects. For that matter, Kepler’s Laws use r² and r³. Couldn’t you juggle them around to evaluate r?”

“Nope. Kepler did ratios, not absolute values. Newton’s Law has r² but you can rewrite it as F ² = GMm/r² = G(M/r)(m/r), G times the product of two mass‑to‑distance ratios. Newton’s G is our least‑accurate physical constant and we don’t have good handles on either of those numerators. Before space flight we just had mass ratios like M/m. We only discovered the Moon’s absolute mass when we orbited it with spacecraft of known mass. That’s the lowest rung on our mass ladder. Inside the Solar System we go step by step with orbit ratios. Outside the system everything’s measured relative to Solar mass.”

“I’m getting the ladder idea. So how do you distances?”

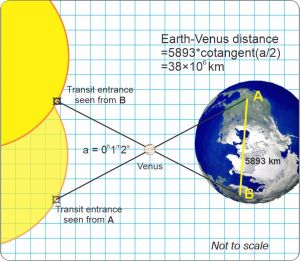

“Lowest rung is parallax, like binocular vision. You look at something from two different points a known distance apart. Measure the angle between the sight‑lines. Figure the triangles to get the something’s distance. The earliest example I know of was in the mid‑1700s when astrometers thousands of miles apart on Earth watched Venus cross the Sun’s disk. Each recorded the precise time they saw Venus touch the Sun’s disk. Given the time shift and the on‑Earth distance, some trigonometry gave them the Earth‑Venus distance. That put a scale to Newtonian orbital diagrams. Parallax across the width of Earth’s orbit yielded stellar distances out to thousands of lightyears with Hubble. We expect ten times better from Gaia.”

“That gets you maybe across the Milky Way. What about farther out?”

“Several ingenious variations on the parallax idea, but mostly standard candles.”

“Candles?”

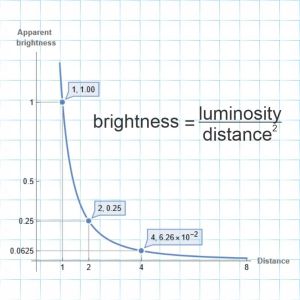

“Suppose you measure the brightness of a candle that’s a known distance away and there’s an equally luminous candle some unknown distance away. Measured brightness falls as the square of the distance, so if the second candle appears half as bright it’s four times the distance and so on. Climbing the cosmic distance ladder is going from one kind of uniformly‑luminous candle to another kind farther away.”

“Such as?”

“We know how brightness relates to bright‑dim‑bright cycle time for several types of variable stars. That gets us out to 30 million lightyears or so. Type I‑a supernovas act as useful candles out to a billion lightyears. Beyond that we can use galaxy surface brightness. That’s where the recent argument started.”

~ Rich Olcott

- Thanks to Ken Burke for mentioning tellurium‑128’s septillion‑year half‑life.

Those two electrons push their dust grains apart almost a quintillion times more strongly than gravity pulls them together. And the distance makes no difference — close together or far apart, push wins. You can’t use gravity to build a planet from charged particles.”

Those two electrons push their dust grains apart almost a quintillion times more strongly than gravity pulls them together. And the distance makes no difference — close together or far apart, push wins. You can’t use gravity to build a planet from charged particles.” “Good question. If protons were more positive than electrons, electrostatic repulsion would always be proportional to mass. We couldn’t separate that force from gravity. Physicists have separately measured electron and proton charge. They’re equal (except for sign) to 10 decimal places. Unfortunately, we’d need another 25 digits of accuracy before we could test your hypothesis.”

“Good question. If protons were more positive than electrons, electrostatic repulsion would always be proportional to mass. We couldn’t separate that force from gravity. Physicists have separately measured electron and proton charge. They’re equal (except for sign) to 10 decimal places. Unfortunately, we’d need another 25 digits of accuracy before we could test your hypothesis.”

Sure enough, that’s a straight line (see the chart). Reminds me of how Newton’s Law of Gravity is valid

Sure enough, that’s a straight line (see the chart). Reminds me of how Newton’s Law of Gravity is valid