Things were simpler in the pre-Enlightenment days when we only five planets to keep track of. But Haley realized that comets could have orbits, Herschel discovered Uranus, and Galle (with Le Verrier’s guidance) found Neptune. Then a host of other astronomers detected Ceres and a host of other asteroids, and Tombaugh observed Pluto in 1930.

Astronomers relished the proliferation — every new-found object up there was a new test case for challenging one or another competing theory.

Here’s the currently accepted narrative… Long ago but quite close-by, there was a cloud of dust in the Milky Way galaxy. Random motion within it produced a swirl that grew into a vortex dozens of lightyears long.

Consider one dust particle (we’ll call it Isaac) afloat in a slice perpendicular to the vortex. Assume for the moment that the vortex is perfectly straight, the dust is evenly spread across it, and all particles have the same mass. Isaac is subject to two influences — gravitational and rotational.

out of balance and giving rise

to a solar system.

Gravity pulls Isaac towards towards every other particle in the slice. Except for very near the slice’s center there are generally more particles (and thus more mass) toward and beyond the center than back toward the edge behind him. Furthermore, there will generally be as many particles to Isaac’s left as to his right. Gravity’s net effect is to pull Isaac toward the vortex center.

But the vortex spins. Isaac and his cohorts have angular momentum, which is like straight-line momentum except you’re rotating about a center. Both of them are conserved quantities — you can only get rid of either kind of momentum by passing it along to something else. Angular momentum keeps Isaac rotating within the plane of his slice.

An object’s angular momentum is its linear momentum multiplied by its distance from the center. If Isaac drifts towards the slice’s center (radial distance decreases), either he speeds up to compensate or he transfers angular momentum to other particles by colliding with them.

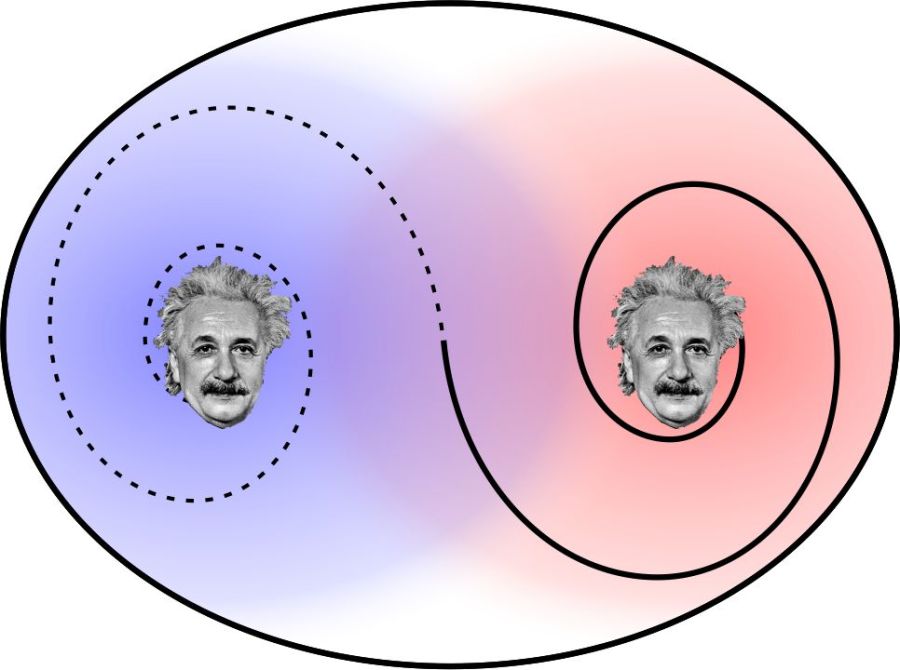

But vortices are rarely perfectly straight. Moreover, the galactic-cloud kind are generally lumpy and composed of different-sized particles. Suppose our vortex gets kinked by passing a star or a magnetic field or even another vortex. Between-slice gravity near the kink shifts mass kinkward and unbalances the slices to form a lump (see the diagram). The lump’s concentrated mass in turn attracts particles from adjacent slices in a viscous cycle (pun intended).

After a while the lumpward drift depletes the whole neighborhood near the kink. The vortex becomes host to a solar nebula, a concentrated disk of dust whirling about its center because even when you come in from a different slice, you’ve still got your angular momentum. When gravity smacks together Isaac and a few billion other particles, the whole ball of whacks inherits the angular momentum that each of its stuck-together components had. Any particle or planetoid that tries to make a break for it up- or down-vortex gets pulled back into the disk by gravity.

That theory does a pretty good job on the conventional Solar System — four rocky Inner Planets, four gas giant Outer Planets, plus that host of asteroids and such, all tightly held in the Plane of The Ecliptic.

How then to explain out-of-plane objects like Pluto and Eris, not to mention long-period comets with orbits at all angles?

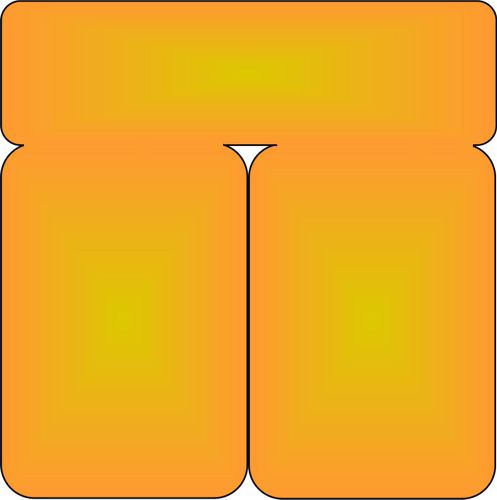

We now know that the Solar System holds more than we used to believe. Who’s in is still “objects whose motion is dominated by the Sun’s gravitational field,” but the Sun’s net spreads far further than we’d thought. Astronomers now hypothesize that after its creation in the vortex, the Sun accumulated an Oort cloud — a 100-billion-mile spherical shell containing a trillion objects, pebbles to planet-sized.

At the shell’s average distance from the Sun (see how tiny Neptune’s path is in the diagram) Solar gravity is a millionth of its strength at Earth’s orbit. The gravity of a passing star or even a conjunction of our own gas giants is enough to start an Oort-cloud object on an inward journey.

These trans-Neptunian objects are small and hard to see, but they’re revolutionizing planetary astronomy.

~~ Rich Olcott

This video, from an Orbits Table display at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, shows a different Plutonian weirdness. We’re circling the Solar System at about 50 times Earth’s distance from the Sun (50 AU). Reading inward, the white lines represent the orbits of Neptune, Uranus, Saturn and Jupiter. The Asteroid Belt is the small greenish ring close to the Sun. The four terrestrial planets are even further in. The Kuiper Belt is the greenish ring that encloses the lot.

This video, from an Orbits Table display at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, shows a different Plutonian weirdness. We’re circling the Solar System at about 50 times Earth’s distance from the Sun (50 AU). Reading inward, the white lines represent the orbits of Neptune, Uranus, Saturn and Jupiter. The Asteroid Belt is the small greenish ring close to the Sun. The four terrestrial planets are even further in. The Kuiper Belt is the greenish ring that encloses the lot.

One more step and we can answer Ken’s question. A moving object’s proper time is defined to be the time measured by a clock affixed to that object. The proper time interval between two events encountered by an object is exactly Minkowski’s spacetime interval. Lucy’s clock never moves from zero.

One more step and we can answer Ken’s question. A moving object’s proper time is defined to be the time measured by a clock affixed to that object. The proper time interval between two events encountered by an object is exactly Minkowski’s spacetime interval. Lucy’s clock never moves from zero.

It would have been awesome to watch Dragon Princes in battle (from a safe hiding place), but I’d almost rather have witnessed “The Tussles in Brussels,” the two most prominent confrontations between Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr.

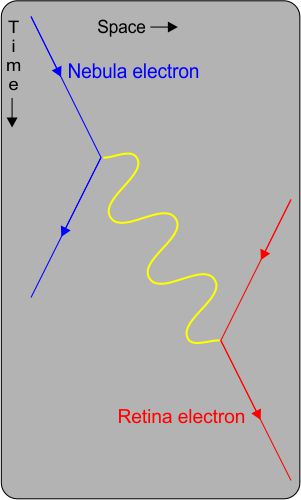

It would have been awesome to watch Dragon Princes in battle (from a safe hiding place), but I’d almost rather have witnessed “The Tussles in Brussels,” the two most prominent confrontations between Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr. Like Newton, Einstein was a particle guy. He based his famous thought experiments on what his intuition told him about how particles would behave in a given situation. That intuition and that orientation led him to paradoxes such as entanglement, the

Like Newton, Einstein was a particle guy. He based his famous thought experiments on what his intuition told him about how particles would behave in a given situation. That intuition and that orientation led him to paradoxes such as entanglement, the  Bohr was six years younger than Einstein. Both Bohr and Einstein had attained Directorship of an Institute at age 35, but Bohr’s has his name on it. He started out as a particle guy — his first splash was a trio of papers that treated the hydrogen atom like a one-planet solar system. But that model ran into serious difficulties for many-electron atoms so Bohr switched his allegiance from particles to Schrödinger’s wave theory. Solve a Schrödinger equation and you can calculate statistics like

Bohr was six years younger than Einstein. Both Bohr and Einstein had attained Directorship of an Institute at age 35, but Bohr’s has his name on it. He started out as a particle guy — his first splash was a trio of papers that treated the hydrogen atom like a one-planet solar system. But that model ran into serious difficulties for many-electron atoms so Bohr switched his allegiance from particles to Schrödinger’s wave theory. Solve a Schrödinger equation and you can calculate statistics like  Here’s where Ludwig Wittgenstein may have come into the picture. Wittgenstein is famous for his telegraphically opaque writing style and for the fact that he spent much of his later life disagreeing with his earlier writings. His 1921 book, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (in German despite the Latin title) was a primary impetus to the Logical Positivist school of philosophy. I’m stripping out much detail here, but the book’s long-lasting impact on QM may have come from its Proposition 7: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.“

Here’s where Ludwig Wittgenstein may have come into the picture. Wittgenstein is famous for his telegraphically opaque writing style and for the fact that he spent much of his later life disagreeing with his earlier writings. His 1921 book, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (in German despite the Latin title) was a primary impetus to the Logical Positivist school of philosophy. I’m stripping out much detail here, but the book’s long-lasting impact on QM may have come from its Proposition 7: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.“

Information transfer at infinite speed? Of course not, because neither hungry person knows what’s in either box until they open one or until they exchange information. Even Skype operates at light-speed (or slower).

Information transfer at infinite speed? Of course not, because neither hungry person knows what’s in either box until they open one or until they exchange information. Even Skype operates at light-speed (or slower).

Nonetheless, mathematicians and cryptographers have forged ahead, calculating π to more than a trillion digits. Here for your enjoyment are the 99 digits that come after digit million….

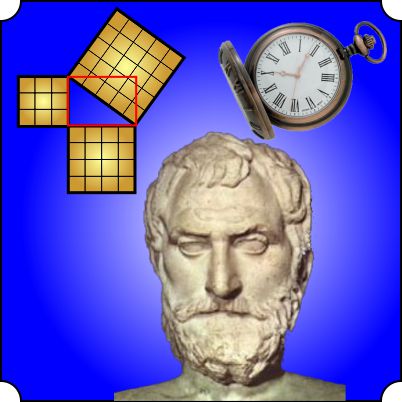

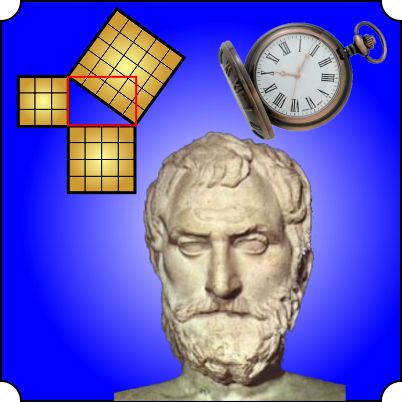

Nonetheless, mathematicians and cryptographers have forged ahead, calculating π to more than a trillion digits. Here for your enjoyment are the 99 digits that come after digit million…. Back to π. The Greeks knew that the circumference of a circle (c) divided by its diameter (d) is π. Furthermore they knew that a circle’s area divided by the square of its radius (r) is also π. Euclid was too smart to try calculating the area of the visible sky in his astronomical work. He had two reasons — he didn’t know the radius of the horizon, and he didn’t know the height of the sky. Later geometers worked out the area of such a spherical cap. I was pleased to learn that π is the ratio of the cap’s area to the square of its chord, s2=r2+h2.

Back to π. The Greeks knew that the circumference of a circle (c) divided by its diameter (d) is π. Furthermore they knew that a circle’s area divided by the square of its radius (r) is also π. Euclid was too smart to try calculating the area of the visible sky in his astronomical work. He had two reasons — he didn’t know the radius of the horizon, and he didn’t know the height of the sky. Later geometers worked out the area of such a spherical cap. I was pleased to learn that π is the ratio of the cap’s area to the square of its chord, s2=r2+h2. Astrophysicists and cosmologists look at much bigger figures, ones so large that curvature has to be figured in. There are three possibilities

Astrophysicists and cosmologists look at much bigger figures, ones so large that curvature has to be figured in. There are three possibilities

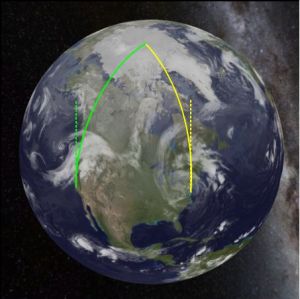

For instance, suppose Fred and Ethel collaborate on a narwhale research project. Fred is based in San Diego CA and Ethel works out of Norfolk VA. They fly to meet their research vessel at the North Pole. Fred’s plane follows the green track, Ethel’s plane follows the yellow one. At the start of the trip, they’re on parallel paths going straight north (the dotted lines). After a few hours, though, Ethel notices the two planes pulling closer together.

For instance, suppose Fred and Ethel collaborate on a narwhale research project. Fred is based in San Diego CA and Ethel works out of Norfolk VA. They fly to meet their research vessel at the North Pole. Fred’s plane follows the green track, Ethel’s plane follows the yellow one. At the start of the trip, they’re on parallel paths going straight north (the dotted lines). After a few hours, though, Ethel notices the two planes pulling closer together.

The line rotates as a unit — every skater completes a 360o rotation in the same time. Similarly, everywhere on Earth a day lasts for exactly 24 hours.

The line rotates as a unit — every skater completes a 360o rotation in the same time. Similarly, everywhere on Earth a day lasts for exactly 24 hours. Now suppose our speedy skater hits a slushy patch of ice. Her end of the line is slowed down, so what happens to the rest of the line? It deforms — there’s a new center of rotation that forces the entire line to curl around towards the slow spot. Similarly, that blob near the Equator in the split-Earth diagram curls in the direction of the slower-moving air to its north, which is counter-clockwise.

Now suppose our speedy skater hits a slushy patch of ice. Her end of the line is slowed down, so what happens to the rest of the line? It deforms — there’s a new center of rotation that forces the entire line to curl around towards the slow spot. Similarly, that blob near the Equator in the split-Earth diagram curls in the direction of the slower-moving air to its north, which is counter-clockwise.