“Hey, Cathleen, while we’re talking IceCube, could you ‘splain one other thing from that TV program?”

“Depends on the program, Al.”

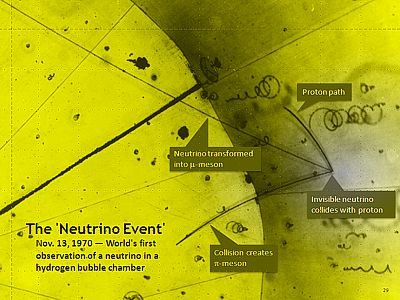

“Oh, yeah, you weren’t here when we started on this. So I was watching this program and they were talking about neutrinos and how there’s trillions of them going through like my thumbnail every second and then IceCube saw this one neutrino that they’re real excited about so what I’m wondering is, what’s so special about just that neutrino? How do they even tell it apart from all the others?”

“How about the direction it came from, Cathleen? We get lotsa neutrinos from the Sun and this one shot in from somewhere else?”

“An interesting question, Vinnie. The publicity did concern its direction, but the neutrino was already special. It registered 290 tera-electron-volts.”

“Ter-what?”

“Sorry, scientific shorthand — tera is ten-to-the-twelfth. A million electrons poised on a million-volt gap would constitute a Tera-eV of potential energy. Our Big Guy had 290 times that much kinetic energy all by himself.”

“How’s that stack up against other neutrinos?”

“Depends on where they came from. Neutrinos from a nuclear reactor’s uranium or plutonium fission carry only about 10 Mega-eV, wimpier by a factor of 30 million. The Sun’s primary fusion process generates neutrinos peaking out at 0.4 MeV, 25 times weaker still.”

“How about from super-accelerators like the LHC?”

“Mmm, the LHC makes TeV-range protons but it’s not designed for neutrino production. We’ve got others that have been pressed into service as neutrino-beamers. It’s a complicated process — you send protons crashing into a target. It spews a splatter of pions and K-ons. Those guys decay to produce neutrinos that mostly go in the direction you want. You lose a lot of energy. Last I looked the zippiest neutrinos we’ve gotten from accelerators are still a thousand times weaker than the Big Guy.”

I can see the question in Vinnie’s eyes so I fire up Old Reliable again. Here it comes… “What’s the most eV’s it can possibly be?” Good ol’ Vinnie, always goes for the extremes.

“You remember the equation for kinetic energy?”

“Sure, it’s E=½ m·v², learned that in high school.”

“And it stayed with you. OK, and what’s the highest possible speed?”

“Speed o’ light, 186,000 miles per second.”

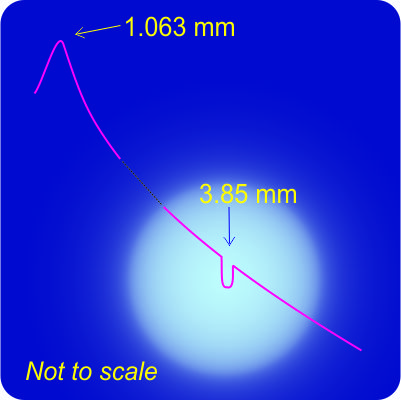

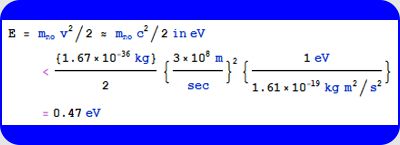

“Or 300 million meters per second, ’cause that’s Old Reliable’s default setting. Suppose we’ve got a neutrino that’s going a gnat’s whisker slower than light. Let’s apply that formula to the neutrino’s rest mass which is something less than 1.67×10-36 kilograms…” “Half an eV? That’s all? So how come the Big Guy’s got gazillions of eV’s?”

“Half an eV? That’s all? So how come the Big Guy’s got gazillions of eV’s?”

“But the Big Guy’s not resting. It’s going near lightspeed so we need to apply that relativistic correction to its mass… “That infinity sign at the bottom means ‘as big as you want.’ So to answer your first question, there isn’t a maximum neutrino energy. To make a more energetic neutrino, just goose it to go even closer to the speed of light.”

“That infinity sign at the bottom means ‘as big as you want.’ So to answer your first question, there isn’t a maximum neutrino energy. To make a more energetic neutrino, just goose it to go even closer to the speed of light.”

“Musta been one huge accelerator that spewed the Big Guy.”

“One of the biggest, Al.” Cathleen again. “That’s the exciting thing about what direction the particle came from.”

“Like the North Pole or something?”

“Much further away, much bigger and way more interesting. As soon as IceCube caught that neutrino signal, it automatically sent out a “Look in THIS direction!” alert to conventional observatories all over the world. And there it was — a blazar, 5.7 billion lightyears away!”

“Wait, Cathleen, what’s a blazar?”

“An incredibly brilliant but highly variable photon source, from radio frequencies all the way up to gamma rays and maybe cosmic rays. We think the thousands we’ve catalogued are just a fraction of the ones within range. We’re pretty sure that each of them depends on a super-massive black hole in the center of a galaxy. The current theory is that those photons come from an astronomy-sized accelerator, a massive swirling jet that shoots out from the central source. When the jet happens to point straight at us, flash-o!”

“Duck!”

“I wouldn’t worry about a neutrino flood. The good news is IceCube’s signal alerted astronomers to check TXS 0506+056, a known blazar, early in a new flare cycle.”

“An astrophysical fire alarm!”

~~ Rich Olcott

“Thanks, Sy. Look, we’ve got three intervals where everything syncs up. See the new satellite peaks half-way in between? There’s more hidden pattern where things look chaotic in the rest of the space.”

“Thanks, Sy. Look, we’ve got three intervals where everything syncs up. See the new satellite peaks half-way in between? There’s more hidden pattern where things look chaotic in the rest of the space.”

“Hello, Jennie. Haven’t seen you for a while.”

“Hello, Jennie. Haven’t seen you for a while.” Momentum is velocity times mass. These guys fly so close to lightspeed that for a long time scientists thought that neutrinos are massless like photons. They’re not, so I used several different v/c ratios to see what the relativistic correction does. Slow neutrinos are huge, by atom standards. Even the fastest ones are hundreds of times wider than a nucleus.”

Momentum is velocity times mass. These guys fly so close to lightspeed that for a long time scientists thought that neutrinos are massless like photons. They’re not, so I used several different v/c ratios to see what the relativistic correction does. Slow neutrinos are huge, by atom standards. Even the fastest ones are hundreds of times wider than a nucleus.” “Wait, right ascension in hours-minute-seconds but declination in degrees?”

“Wait, right ascension in hours-minute-seconds but declination in degrees?”

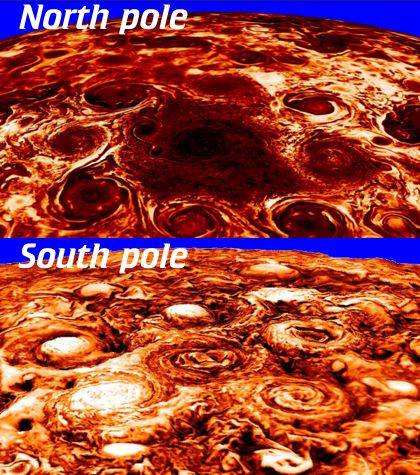

“They’re certainly eye-catching, but I thought Jupiter’s all baby-blue and salmon-colored.”

“They’re certainly eye-catching, but I thought Jupiter’s all baby-blue and salmon-colored.”

“Not much. We can’t see it, and they say there is much more of it than the matter we can see. If we can’t see it, how did she find it? That’s a thing I don’t understand, what I came to your office to ask.”

“Not much. We can’t see it, and they say there is much more of it than the matter we can see. If we can’t see it, how did she find it? That’s a thing I don’t understand, what I came to your office to ask.”