Vinnie takes a long thoughtful look at the image that had dashed his beautiful six‑universe idea. “Wait, Sy. I don’t like this picture”

“Because it messes up your invention?”

“No, because how can they know what that halo looks like? I mean, the whole thing with dark matter is that we can’t see it.”

“You’re right about that. Dark matter’s so transparent that even with five times more mass than normal matter, it doesn’t block CMB photons coming from 13.8 billion lightyears away. That still boggles my brain every once in a while. But dark matter’s gravitational effects — those we can see.”

“Yeah, I remember a long time ago we talked about Fritz Zwicky and Vera Rubin and how they told people about galaxies held together by too much gravity but nobody believed them.”

“Well, they did, after a while—”

“A long while, like a long while since those talks. Remind me what ‘too much gravity’ was about.”

“It was about conflicts between their observations and the prevailing theoretical models. Everyone thought that galaxies and galaxy clusters should operate pretty much like planetary orbits — your speed increases the closer you are to the center, up to Einstein’s speed limit. Newton’s Laws of Motion predict how fast you should move if you’re at a certain distance from a body with a certain mass. If you’re moving faster than that, you fly away.”

“Yeah, escape velocity. So the galaxies in Zwicky’s cluster didn’t follow Newton’s Laws?”

“They didn’t seem to. Galaxies that should have escaped were still in there. The only way he could explain the stability was to suppose the galaxies are only a small fraction of the cluster’s mass. Extra gravity from the extra mass must bind things together. Forty years later Rubin’s improved technology revealed that stars within galaxies had the same anomalous motion.”

“I’m guessing the ‘faster near the center’ rule didn’t hold, or else you wouldn’t be telling this story. Spun like a wheel, I bet.”

“When a wheel spins, every part of it rotates at the same angular speed, the same number of degrees per second, right?”

“Ahh, the bigger my circle the higher my airspeed so the rule would be ‘faster farther out’.”

“That’s the wheel rule, right, but Rubin’s data showed that stars within galaxies don’t obey that one either. She measured lots of stars in Andromeda and other galaxies. Their linear speeds, kilometers per second, are nearly identical from near the center all the way out. Even dust and gas clouds beyond the galactic starry edges also fit the ‘same linear speed everywhere’ rule. You’d lose the bet.”

“That just doesn’t feel right. How can just gravity make that happen?”

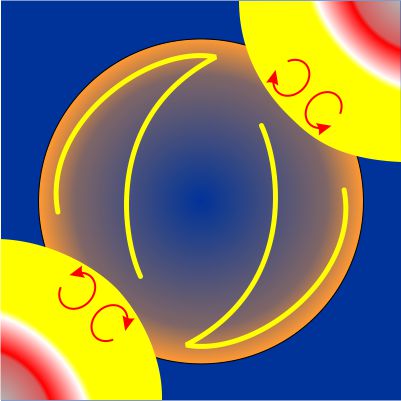

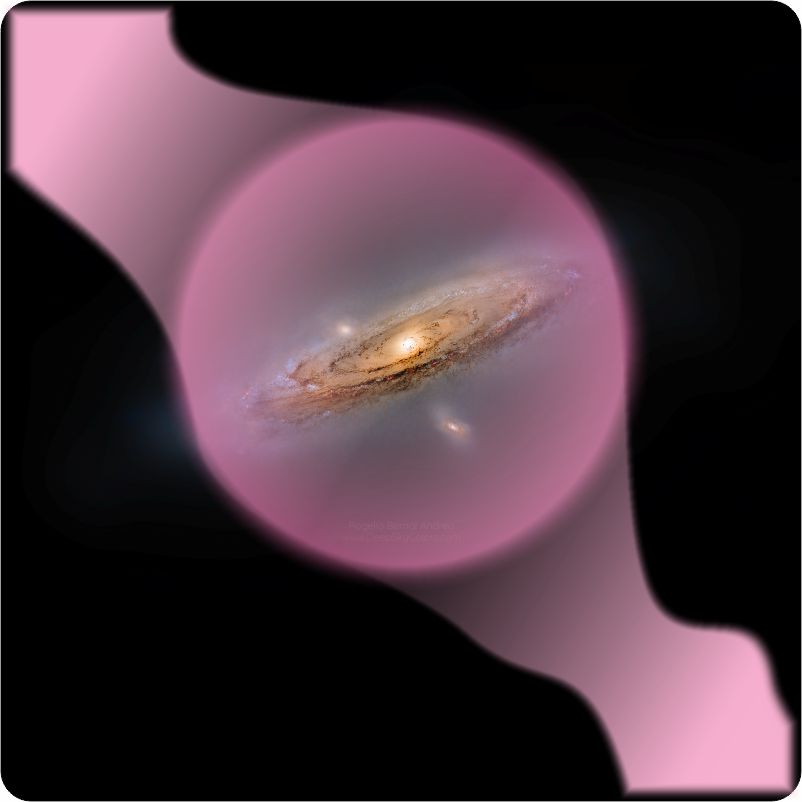

“It can if the right amount of dark matter’s distributed in the right‑shaped smeared‑out hollowed‑out spherical halo. The halo’s radial density profile looks about like this. Of course, profiles for different galaxies differ in spread‑outness and other details, but the models are pretty consistent.”

“Wait, if dark matter only does gravity like you said, why’s that hole in the middle? Why doesn’t everything just fall inward?”

“Dark matter has mass so it also has inertia, momentum and angular momentum, just as normal matter does. Suppose some of the dark matter has collected gravitationally into a blob and the blob is moving slower than escape velocity. If it’s flying straight at the center of gravity it’ll get there and stay there, more or less. But if the blob’s aimed in any other direction, it has angular momentum relative to the center. Momentum’s conserved for dark matter, too. The blob eventually goes into orbit and winds up as part of the shell.”

“Does Zwicky’s galaxy cluster have a halo, too?”

“Not in the same way. Each galaxy probably has its own halo but the galaxies are far apart relative to their size. The theoreticians have burned huge amounts of computer time simulating the chaos inside large ensembles of gravity‑driven blobs. I just read one paper about a 4‑billion‑particle calculation and mind you, a ‘particle’ in this study carried more than a million solar masses. Big halos host subhalos, with filaments of minihalos tying them together. What we can’t see is complicated, too.”

~ Rich Olcott

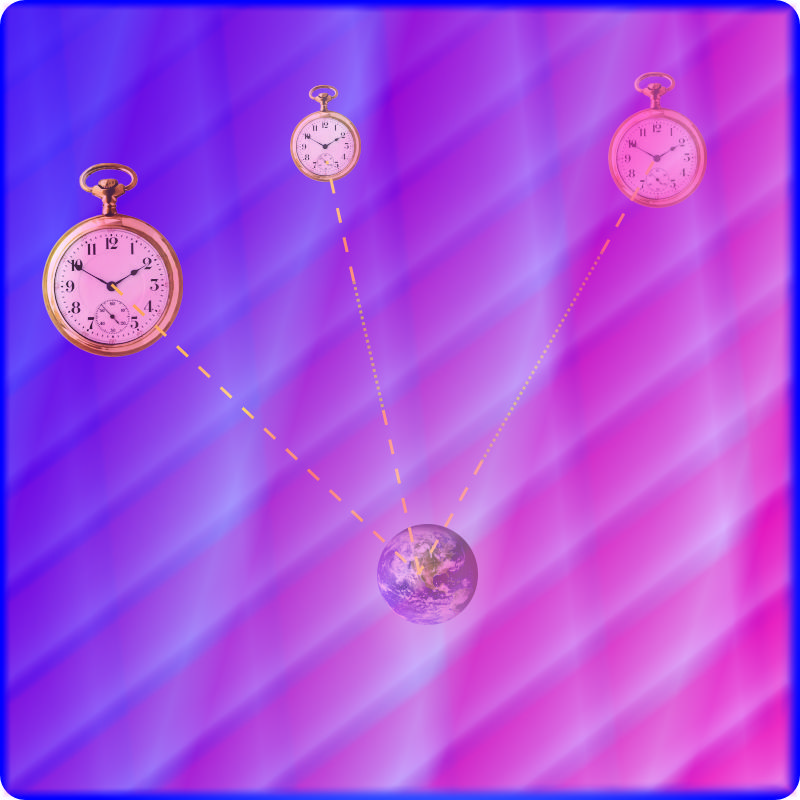

“Gravitational waves are relativity effects and neutrinos are quantum mechanical. Physicists have been struggling for a century to bridge those two domains. Evidence from a three-messenger event could provide the final clues.”

“Gravitational waves are relativity effects and neutrinos are quantum mechanical. Physicists have been struggling for a century to bridge those two domains. Evidence from a three-messenger event could provide the final clues.”

“Wait, Mr Moire, we said that the event horizon’s just a mathematical construct,

“Wait, Mr Moire, we said that the event horizon’s just a mathematical construct,