“By the way, Cathleen, is there any rhyme or reason to that three-object object‘s funky name? I’ve still got it on Old Reliable here.”

PSR J0337+1715

“It’s nothing like funky, Sy, it’s perfectly reasonable and in fact it’s far more informative than a name like ‘Barnard’s Star.’ The ‘PSR‘ part says that the active object, the reason anyone even looked in that system’s direction, is a pulsar.”

“And the numbers?”

“Its location in two parts. Imagine a 24-hour clockface in the Solar Plane. The zero hour points to where the Sun is at the Spring equinox. One o’clock is fifteen degrees east of that, two o’clock is another fifteen degrees eastward and so on until 24 o’clock is back pointing at the Springtime Sun. Got that?”

“Mm, … yeah. It’d be like longitudes around the Earth, except the Earth goes around in a day and this clock looks like it measures a year.”

“Careful there, it has nothing to do with time. It’s just a measure of angle around the celestial equator. It’s called right ascension.”

“How about intermediate angles, like between two and three o’clock?”

“Sixty arc-minutes between hours, sixty arc-seconds between arc-minutes, just like with time. If you need to you can even go to tenths or hundredths of an arc-second, which divide the circle into … 8,640,000 segments.”

“OK, so if that’s like longitudes, I suppose there’s something like latitudes to go with it?”

“Mm-hm, it’s called declination. It runs perpendicular to ascension, from plus-90° up top down to 0° at the clockface to minus-90° at the bottom. Vivian, show Sy Figure 3 from your paper.” “Wait, right ascension in hours-minute-seconds but declination in degrees?”

“Wait, right ascension in hours-minute-seconds but declination in degrees?”

“Mm-hm. Blame history. People have been studying the stars and writing down their locations for a long time. Some conventions were convenient back in the day and we’re not going to give them up. So anyway, an object’s J designation with 4-digit numbers tells you which of 13 million directions to look to find it. Roughly.”

“Roughly?”

“That’s what the ‘J‘ is about. If the Earth’s rotation were absolutely steady and if the Sun weren’t careening about a moving galaxy, future astronomers could just look at an object’s angular designation and know exactly where to look to find it again. But it’s not and it does and they won’t. The Earth’s axis of rotation wobbles in at least three different ways, the Sun’s orbit around the galaxy is anything but regular and so on. Specialists in astrometry, who measure things to fractions of an arc-second, keep track of time in more ways than you can imagine so we can calculate future positions. The J-names at least refer back to a specific point in time. Mostly. You want your mind bent, look up epoch some day.”

“Plane and ship navigators care, too, right?”

“Not so much. Earth’s major wobble, for instance, shifts our polar positions only about 40 parts per million per year. A course you plotted last week from here to Easter Island will get you there next month no problem.”

Old Reliable judders in my hand. Old Reliable isn’t supposed to have a vibration function, either. Ask her about interstellar navigation. “Um, how about interstellar navigation?”

“Oh, that’d be a challenge. Once you get away from the Solar System you can’t use the Big Dipper to find the North Star, any of that stuff, because the constellations look different from a different angle. Get a couple dozen lightyears out, you’ve got a whole different sky.”

“So what do you use instead?”

“I suppose you could use pulsars. Each one pings at a unique repetition interval and duty cycle so you could recognize it from any angle. The set of known pulsars would be like landmarks in the galaxy. If you sent out survey ships, like the old-time navigators who mapped the New World, they could add new pulsars to the database. When you go someplace, you just triangulate against the pulsars you see and you know where you are.”

If they happen to point towards you! You only ever see 20% of them. Starquakes and glitches and relativistic distortions mess up the timings. Poor Xian-sheng goes nuts each time we drop out of warp.

~~ Rich Olcott

Cathleen saves me from answering. “Not quite. The study Sy’s chasing is actually a cute variation on red-shift measurements. That ‘PSR‘ designation means the neutron star is a pulsar. Those things emit electromagnetic radiation pulses with astounding precision, generally regular within a few dozen nanoseconds. If we receive slowed-down pulses then the object’s going away; sped-up and it’s approaching, just like with red-shifting. The researchers derived orbital parameters for all three bodies from the between-pulse durations. The heavy dwarf is 200 times further out than the light one, for instance. Not an easy experiment, but it yielded an important result.”

Cathleen saves me from answering. “Not quite. The study Sy’s chasing is actually a cute variation on red-shift measurements. That ‘PSR‘ designation means the neutron star is a pulsar. Those things emit electromagnetic radiation pulses with astounding precision, generally regular within a few dozen nanoseconds. If we receive slowed-down pulses then the object’s going away; sped-up and it’s approaching, just like with red-shifting. The researchers derived orbital parameters for all three bodies from the between-pulse durations. The heavy dwarf is 200 times further out than the light one, for instance. Not an easy experiment, but it yielded an important result.”

“Not much. We can’t see it, and they say there is much more of it than the matter we can see. If we can’t see it, how did she find it? That’s a thing I don’t understand, what I came to your office to ask.”

“Not much. We can’t see it, and they say there is much more of it than the matter we can see. If we can’t see it, how did she find it? That’s a thing I don’t understand, what I came to your office to ask.”

“So you’re telling me, Cathleen, that you can tell how hot a star is by

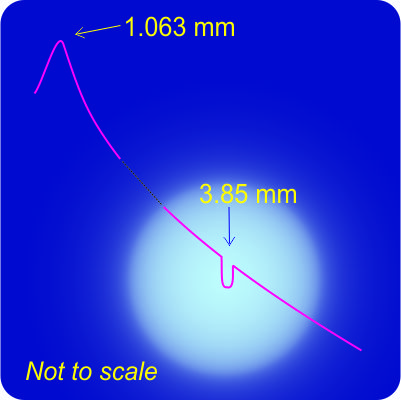

“So you’re telling me, Cathleen, that you can tell how hot a star is by  Cathleen turns to her laptop and starts tapping keys. “Let’s do an example. Suppose we’re looking at a star’s broadband spectrogram. The blackbody curve peaks at 720 picometers. There’s an absorption doublet with just the right relative intensity profile in the near infra-red at 1,060,190 and 1,061,265 picometers. They’re 1,075 picometers apart. In the lab, the sodium doublet’s split by 597 picometers. If the star’s absorption peaks are indeed the sodium doublet then the spectrum has been stretched by a factor of 1075/597=1.80. Working backward, in the star’s frame its blackbody peak must be at 720/1.80=400 picometers, which corresponds to a temperature of about 6,500 K.”

Cathleen turns to her laptop and starts tapping keys. “Let’s do an example. Suppose we’re looking at a star’s broadband spectrogram. The blackbody curve peaks at 720 picometers. There’s an absorption doublet with just the right relative intensity profile in the near infra-red at 1,060,190 and 1,061,265 picometers. They’re 1,075 picometers apart. In the lab, the sodium doublet’s split by 597 picometers. If the star’s absorption peaks are indeed the sodium doublet then the spectrum has been stretched by a factor of 1075/597=1.80. Working backward, in the star’s frame its blackbody peak must be at 720/1.80=400 picometers, which corresponds to a temperature of about 6,500 K.”

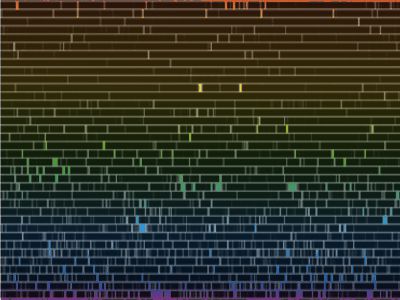

“You’re right, Sy. It’s not a particularly pretty picture, but it shows that nice strong sodium doublet in the yellow and the broad iron and hydrogen lines down in the green and blue. I’ll admit it, Vinnie, this is a faked image I made to show my students what the solar atmosphere would look like if you could turn off the photosphere’s continuous blast of light. The point is that the atoms emit exactly the same sets of colors that they absorb.”

“You’re right, Sy. It’s not a particularly pretty picture, but it shows that nice strong sodium doublet in the yellow and the broad iron and hydrogen lines down in the green and blue. I’ll admit it, Vinnie, this is a faked image I made to show my students what the solar atmosphere would look like if you could turn off the photosphere’s continuous blast of light. The point is that the atoms emit exactly the same sets of colors that they absorb.”

“Whoa, Sy. Do you read the final chapter of a mystery story before you begin the book?”

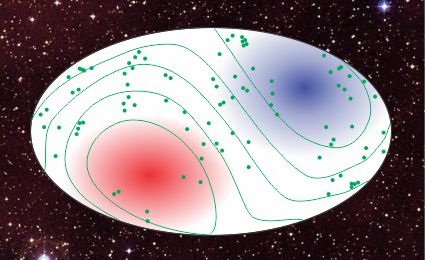

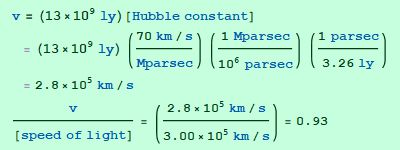

“Whoa, Sy. Do you read the final chapter of a mystery story before you begin the book?” “It is, Sy, and that’s one of the reasons why Hubble’s original number was so far off. He only looked at about 50 close-by galaxies, some of which are moving toward us and some away. You only get a view of the general movement when you look at large numbers of galaxies at long distances. It’s like looking through a window at a snowfall. If you concentrate on individual flakes you often see one flying upward, even though the fall as a whole is downward. Andromeda’s 250,000 mph march towards us is against the general expansion.”

“It is, Sy, and that’s one of the reasons why Hubble’s original number was so far off. He only looked at about 50 close-by galaxies, some of which are moving toward us and some away. You only get a view of the general movement when you look at large numbers of galaxies at long distances. It’s like looking through a window at a snowfall. If you concentrate on individual flakes you often see one flying upward, even though the fall as a whole is downward. Andromeda’s 250,000 mph march towards us is against the general expansion.”