“Bless you, Al, for your air conditioning and your iced coffee.”

“Hiya, Susan. Yeah, you guys do look a little warm. What’ll you have, Sy and Mr Feder?”

“Just my usual mug of mud, Al, and a strawberry scone. Put Susan’s and my orders on Mr Feder’s tab, he’s been asking us questions.”

“Oh? Well, I suppose, but in that case I get another question. Cold brew for me, Al, with ice and put a shot of vanilla in there.”

“So what’s your question?”

“Is sea level rising or not? I got this cousin he keeps sending me proofs it ain’t but I’m reading how NYC’s talking big bucks to build sea walls around Manhattan and everything. Sounds like a big boondoggle.” <pulling a crumpled piece of paper from his pocket and smoothing it out a little> “Here’s something he’s sent me a couple times.”

“That’s bogus, Mr Feder. They don’t tell us moon phase or time of day for either photo. We can’t evaluate the claim without that information. The 28‑day lunar tidal cycle and the 24‑hour solar cycle can reinforce or cancel each other. Either picture could be a spring tide or a neap tide or anything in‑between. That’s a difference of two meters or more.”

“Sy. the meme’s own pictures belie its claim. Look close at the base of the tower. The water in the new picture covers that sloping part of the base that was completely above the surface in the old photo. A zero centimeter rise, my left foot.”

“Good point, Susan. Mind if I join the conversation from a geologist’s perspective? And yes, we have lots of independent data sources that show sea levels are rising in general.”

“Dive right in, Kareem, but I thought you were an old‑rocks guy.”

“I am, but I study old rocks to learn about the rise and fall of land masses. Sea level variation is an important part of that story. It’s way more complicated than what that photo pretends to deny.”

“Okay, I get that tides go up and down so you average ’em out over a day, right? What’s so hard?”

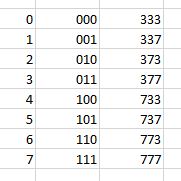

“Your average will be invalid two weeks later, Mr Feder, like Sy said. To suppress the the Sun’s and Moon’s cyclic variations you’d have to take data for a full year, at least, although a decade would be better.”

“I thought they went like clockwork.”

“They do, mostly, but the Earth doesn’t. There’s several kinds of wobbles, a few of which may recently have changed because Eurasia weighs less.”

“Huh?”

”Huh?”

”Huh?”

“Mm-hm, its continental interior is drying out, water fleeing the soil and going everywhere else. That’s 10% of the planet’s surface area, all in the Northern hemisphere. Redistributing so much water to the Southern hemisphere’s oceans changes the balance. The world will spin different. Besides, the sea’s not all that level.”

“Sea level’s not level?”

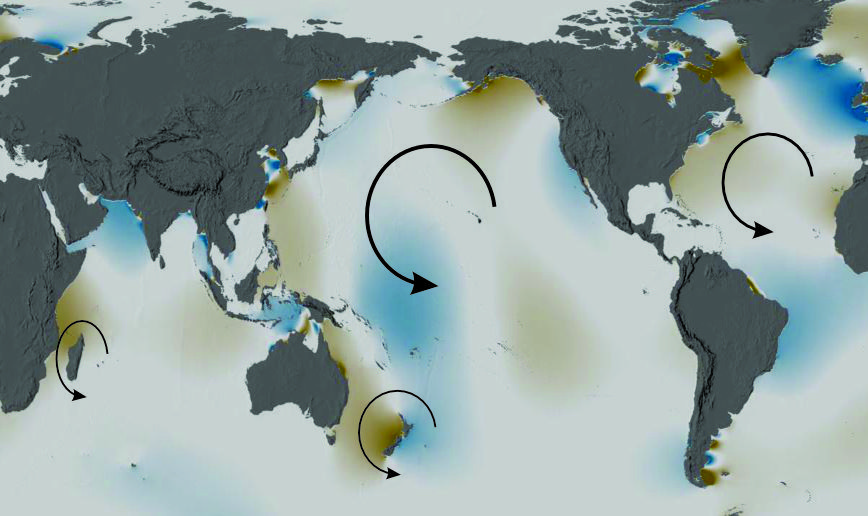

“Nope. Surely you’ve sloshed water in a sink or bathtub. The sea sloshes, too, counterclockwise. Galileo thought sloshing completely accounted for tides, but that was before Newton showed that the Moon’s gravity drives them. NASA used satellite data to build a fascinating video of sea height all over the world. The sea on one side of New Zealand is always about 2 meters higher than on the opposite side but the peak tide rotates. Then there’s storm surges, tsunamis, seiche resonances from coastal and seafloor terrain, gravitational irregularities, lots of local effects.”

Susan, a chemist trained to consider conservation of mass, perks up. “Wait. Greenland and Antarctica are both melting, too. That water plus Eurasia’s has to raise sea level.”

“Not so much. Yes, the melting frees up water mass that had been locked up as land-bound ice. But on the other hand, it also counteracts sea rise’s major driver.”

“Which is?”

“Expansion of hot water. I did a quick calculation. The Mediterranean Sea averages 1500 meters deep and about 15°C in the wintertime. Suppose it all warms up to 35°C. Its sea level would rise by about 3.3 meters, that’s 10 feet! Unfortunately, not much of Greenland’s chilly outflow will get past the Straits of Gibraltar.”

~~ Rich Olcott