I’m nursing my usual mug of eye‑opener in Cal’s Coffee Shop when astronomer Cathleen and chemist Susan chatter in. “Morning, ladies. Cathleen, prepare to be even more smug.”

“Ooo, what should I be smug about?”

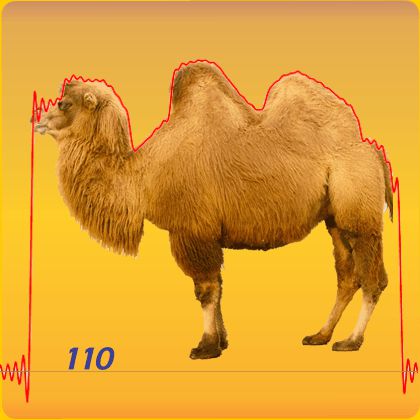

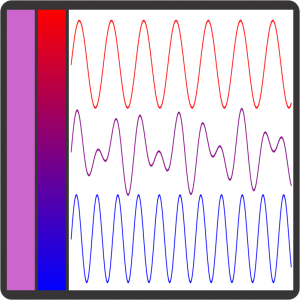

“Your Jupiter suggestion. Grab some coffee and a couple of chairs.” <screen‑tapping on Old Reliable> “Ready? First step — purple and violet. You’ll never see violet or purple light coming from a standard video screen.”

“He’s going spectrum‑y on us, right, Cathleen?”

“More like anti‑spectrum‑y, Susan. Purple light doesn’t exist in the spectrum. We only perceive that color when we see red mixed with blue like that second band on Sy’s display. Violet light is a thing in nature, we can see it in flowers and dyes and rainbows beyond blue. Standard screens can’t show violet because their LEDs just emit red, blue and green wavelengths. Old Reliable uses mixtures of those three to fake all its colors. Where are you going with this, Sy?””

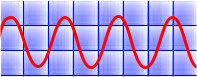

“Deeper into Physics. Cast your eyes upon the squiggles to the right. The one in the middle represents the lightwave coming from purple‑in‑the‑middle. The waveform’s jaggedy, but if you compare peaks and troughs you can see its shape is the sum of the red and blue shapes. I scaled the graphs up from 700 nanometers for red and 450 for blue.”

“Straightforward spectroscopy, Sy, Fourier analysis of a complicated linear waveform. Some astronomers make their living using that principle. So do audio engineers and lots of other people.”

“Patience, Cathleen, I’m going beyond linear. Fourier’s work applies to variation along a line. Legendre and Poisson extended the analysis to—”

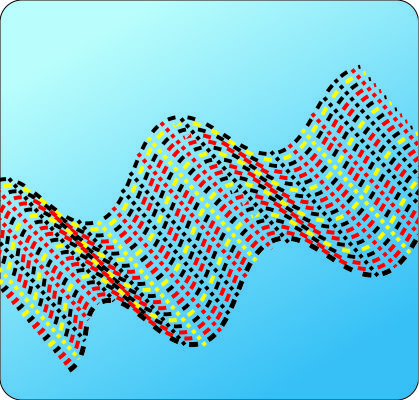

“Aah, spherical harmonics! I remember them from Physical Chemistry class. They’re what gives shapes to atoms. They’ve got electron shells arranged around the nucleus. Electron charge stays as close to the nucleus as quantum will let it. Atoms absorb light energy by moving charge away from there. If the atom’s in a magnetic field or near other atoms that gives it a z-axis direction then the shells split into wavey lumps going to the poles and different directions and that’s your p-, d– and f-orbitals. Bigger shells have more room and they make weird forms but only the transition metals care about that.”

Credit: Inigo.quilez, under CCA SA 3.0 license

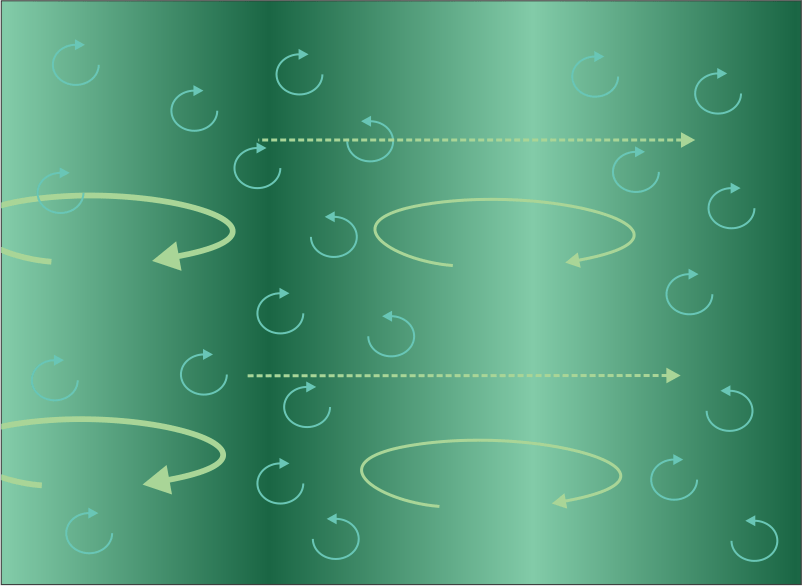

“Considering you left out all the math, Susan, that’s a reasonable summary. I prefer to think of spherical harmonics as combinations of wave shapes at right angles. Imagine a spherical blob of water floating in space. If you tap it on top, waves ripple down to the bottom and back up again and maybe back down again. Those are zonal waves. A zonal harmonic averages over all E‑W longitudes at each N‑S latitude. Or you could stroke the blob on the side and set up a sectorial wave pattern that averages latitudes.”

“How about center‑out radial waves?”

“Susan’s shells do that job. My point was going to be that what sine waves do for characterizing linear things like sound and light, spherical harmonics do for central‑force systems. We describe charge in atoms, yes, but also sound coming from an explosion, heat circulating in a star, gravity shaping a planet. Specifically, Jupiter. Kaspi’s paper you gave me, Cathleen, I read it all the way to the Results table at the tail end. That was the rabbit‑hole.”

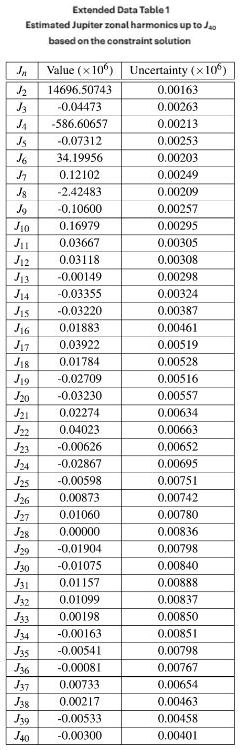

“Oh? What’s in the table?”

“Jupiter’s zonal harmonics — J‑names in the first column, J‑intensities in the second. Jn‘s shape resembles a sine wave and has n zeroes. Jupiter’s never‑zero central field is J0. Jn increases or decreases J0‘s strength wherever it’s non‑zero. For Jupiter that’s mostly by parts per million. What’s cool is the pattern you see when you total the dominating Jeven contributions.”

Cathleen’s squinting in thought. “Hmm… green zone A would be excess gravity from Jupiter’s equatorial bulge. B‘s excess is right where Kaspi proposed the heavy downflow. Ah‑HAH! C‘s pink deficit zone’s right on top of the Great Red Spot’s buoyant updraft. Perfect! Okay, I’m smug.”

~ Rich Olcott