The guy’s got class, I’ll give him that. Astronomer-in-training Jim and Physicist-in-training Newt met his challenges so Change-me Charlie amiably updates his sign.

But he’s not done. “If dark matter’s a thing, how’s it different from dark energy? Mass and energy are the same thing, right, so dark energy’s gotta be just another kind of dark matter. Maybe dark energy’s what happens when real matter that fell into a black hole gets squeezed so hard its energy turns inside out.”

Jim and Newt just look at each other. Even Cap’n Mike’s boggled. Someone has to start somewhere so I speak up. “You’re comparing apples, cabbages and fruitcake. Yeah, all three are food except maybe for fruitcake, but they’re grossly different. Same thing for black holes, dark matter and dark energy — we can’t see any of them directly but they’re grossly different.”

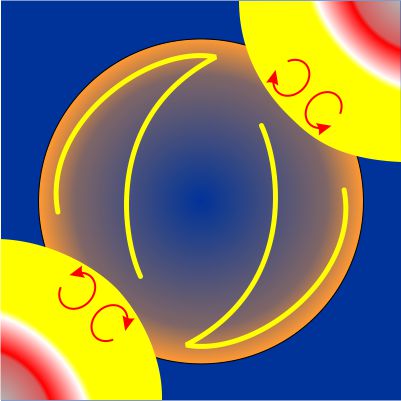

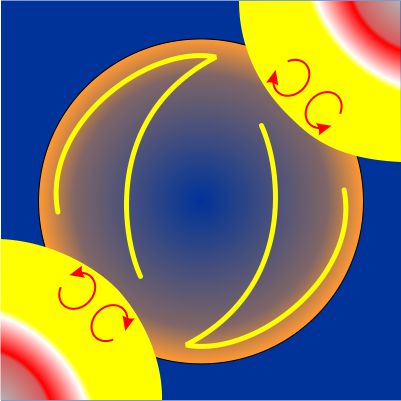

Vinnie’s been listening off to one side but black holes are one of his hobbies. “A black hole’s dark ’cause its singularity’s buried inside its event horizon. Whatever’s outside and somehow gets past the horizon is doomed to fall towards the singularity inside. The singularity itself might be burn-your-eyes bright but who knows, ’cause the photons’re trapped. The accretion disk is really the only lit-up thing showing in that new EHT picture. The black in the middle is the shadow of the horizon, not the hole.”

Jim picks up the tale. “Dark matter’s dark because it doesn’t care about electromagnetism and vice-versa. Light’s an electromagnetic wave — it starts when a charged particle wobbles and it finishes by wobbling another charged particle. Normal matter’s all charged particles — negative electrons and positive nuclei — so normal matter and light have a lot to say to each other. Dark matter, whatever it is, doesn’t have electrical charges so it doesn’t do light at all.”

“Couldn’t a black hole have dark matter in it?”

“From what little we know about dark matter or the inside of a black hole, I see no reason it couldn’t.”

“How about normal matter falls in and the squeezing cooks it, mashes the pluses and minuses together and that’s what makes dark matter?”

“Great idea with a few things wrong with it. The dark matter we’ve found mostly exists in enormous spherical shells surrounding normal-matter galaxies. Your compressed dark matter is in the wrong place. It can’t escape from the black hole’s gravity field, much less get all the way out to those shells. Even if it did escape, decompression would let it revert to normal matter. Besides, we know from element abundance data that there can’t ever have been enough normal matter in the Universe to account for all the dark matter.”

Newt’s been waiting for a chance to cut in. “Dark energy’s dark, too, but it works in the opposite direction from the other two. Gravity from normal matter, black holes or otherwise, pulls things together. So does gravity from dark matter which is how we even learned that it exists. Dark energy’s negative pressure pulls things apart.”

“Could dark energy pull apart a black hole or dark matter?”

Big Cap’n Mike barges in. “Depends on if dark matter’s particles. Particles are localized and if they’re small enough they do quantum stuff. If that’s what dark matter is, dark energy can move the particles apart. My theory is dark matter’s just ripples across large volumes of space so dark energy can change how dark matter’s spread around but it can’t break it into pieces.”

Vinnie stands up for his hobby. “Dark energy can move black holes around, heck it moves galaxies, but like Sy showed us with Old Reliable it’s way too weak to break up black holes. They’re here for the duration.”

Newt pops him one. “The duration of what?”

“Like, forever.”

“Sorry, Hawking showed that black holes evaporate. Really slowly and the big ones slower than the little ones and the temperature of the Universe has to cool down a bit more before that starts to get significant, but not even the black holes are forever.”

“How long we got?”

“Something like 10106 years.”

“That won’t be dark energy’s fault, though.”

~~ Rich Olcott

Cathleen saves me from answering. “Not quite. The study Sy’s chasing is actually a cute variation on red-shift measurements. That ‘PSR‘ designation means the neutron star is a pulsar. Those things emit electromagnetic radiation pulses with astounding precision, generally regular within a few dozen nanoseconds. If we receive slowed-down pulses then the object’s going away; sped-up and it’s approaching, just like with red-shifting. The researchers derived orbital parameters for all three bodies from the between-pulse durations. The heavy dwarf is 200 times further out than the light one, for instance. Not an easy experiment, but it yielded an important result.”

Cathleen saves me from answering. “Not quite. The study Sy’s chasing is actually a cute variation on red-shift measurements. That ‘PSR‘ designation means the neutron star is a pulsar. Those things emit electromagnetic radiation pulses with astounding precision, generally regular within a few dozen nanoseconds. If we receive slowed-down pulses then the object’s going away; sped-up and it’s approaching, just like with red-shifting. The researchers derived orbital parameters for all three bodies from the between-pulse durations. The heavy dwarf is 200 times further out than the light one, for instance. Not an easy experiment, but it yielded an important result.”

Jennie’s turn — “Didn’t the chemists define away a whole lot of entropy when they said that pure elements have zero entropy at absolute zero temperature?”

Jennie’s turn — “Didn’t the chemists define away a whole lot of entropy when they said that pure elements have zero entropy at absolute zero temperature?”