“Afternoon, Al. What’s the ruckus in the back room?”

“Afternoon, Sy. That’s the Astronomy crew and their weekly post-seminar coffee-and-critique session. This time, though, they brought their own beer. You know I don’t have a beer license, just coffee, right? Could you go over there and tell ’em to keep it covered so I don’t get busted?”

“Sure, Al. … Afternoon, folks. What’s all the happy?”

“Hey, Sy, welcome to the party. Trappist beer, straight from Belgium!”

“Don’t mind if I do, Cathleen, but Al sure would like for you to put that carton under the table. Makes him nervous.”

“Sure, no problem.”

“Thanks. I gather your seminar was about the new seven-planet system. How in the world do the Trappists connect to that story?”

“Patriotism. The find was announced by a team from Belgium’s University of Liege. They’ve built a pair of robotic telescopes tailored for seeking out rocks and comets local to our Solar System. Exoplanets, too. Astronomers love tying catchy acronyms to their projects. This group’s proudly Belgian so they called their robots TRAnsiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescopes, ergo TRAPPIST, to honor the country’s 14 monasteries. And their beer. Mainly the beer, I’ll bet.”

“So the planets are a Belgian discovery?”

“Well, the lead investigator, Michaël Gillon, is at Liege, and so are half-a-dozen of his collaborators. Their initial funding came from the Belgian government. But by the time the second paper came out, the one that claimed a full seven planets spanning a new flavor of Goldilocks Zone, they’d pulled in support and telescope time from over a dozen other countries — USA, India, UK, France, Morocco, Saudi Arabia… the list goes on. So it’s Belgian mostly but not only.”

“I love international science. Next question — I see the planets are listed as TRAPPIST-1b, TRAPPIST-1c, and so on up to TRAPPIST-1h. What happened to TRAPPIST-1a?”

“Rules of nomenclature, Sy. TRAPPIST-1a is the star itself. Actually, the star already had a formal name, which I just happen to have written down in my seminar notes somewhere … here it is, 2MASS J23062928 – 0502285. You can see why TRAPPIST-1 is more popular.”

“I’m not even going to ask how that other name unwinds. So what was the seminar topic this week?”

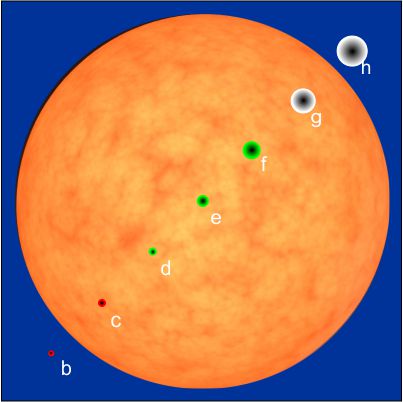

drawn to scale against their star. The

green ones are in the Goldilocks Zone.

“The low probability for us ever noticing those planets blocking the star’s light.”

“I’d think seeing a star winking on and off like it’s sending Morse code would attract attention.”

“That’s not close to what it was doing. It’s all about the scale. You know those cartoons that show planets together with their host sun?”

(showing her my smartphone) “Like this one?”

“Yeah. It’s a lie.”

“How is it lying?”

“It pretends they’re all right next to the star.  This image is a little better.” (showing me her phone) “This artist at least tried to build in some perspective. Even in this tiny solar system, about 1/500 the radius of ours, the star’s distance to each planet is hundreds to a thousand times the size of the planet. You just can’t show planets AND their orbits together in a linear diagram. Now, think about how small these planets are compared to their sun.”

This image is a little better.” (showing me her phone) “This artist at least tried to build in some perspective. Even in this tiny solar system, about 1/500 the radius of ours, the star’s distance to each planet is hundreds to a thousand times the size of the planet. You just can’t show planets AND their orbits together in a linear diagram. Now, think about how small these planets are compared to their sun.”

“Aaaa-hah! When there’s an eclipse, only a small fraction of the light is blocked.”

“That’s part of it. Each eclipse (we call them transits) dims the measured brightness by only a percent or so. But it’s worse than that.”

“How so?”

“How so?”

“All those orbits lie in a single plane. We can’t see the transits unless our position lines up with that plane. If we’re as little as 1½° out of the plane, we miss them. But it’s worse than that.”

“How so?”

“During a transit, each planet casts a conical shadow that defines a patch in TRAPPIST-1’s sky. You can tile TRAPPIST-1’s sky with about 150,000 patches that size. There’s one chance in 150,000 of being in the right patch to see that 1% dimming. In our sky there are over 6×1015 patches the size of TRAPPIST-1h’s orbit. The team had to inspect the just right patch to find it.”

“With odds like that, no wonder TRAPPIST uses robots.”

“Yep.”

~~ Rich Olcott

“OK,

“OK,

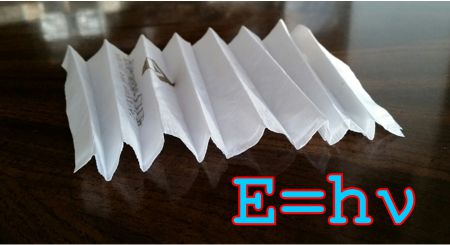

I smoothed out one of Vinnie’s crumpled napkins. As I folded it into pleats and scooted it along the table I said, “Doesn’t mess up the wave so much as change the way we think about it. We’re used to graphing out a spatial wave as an up-and-down pattern like this that moves through time, right?”

I smoothed out one of Vinnie’s crumpled napkins. As I folded it into pleats and scooted it along the table I said, “Doesn’t mess up the wave so much as change the way we think about it. We’re used to graphing out a spatial wave as an up-and-down pattern like this that moves through time, right?”