“Welcome back, Jennie. Why would anyone want to steer an ice cube?”

“Thanks, Jeremy, it’s nice to be back.. And the subject’s not an ice cube, it’s IceCube, the big neutrino observatory in the Antarctic.”

“Then I’m with Al’s question. Observatories have this big dome that rotates and inside there’s a lens or mirror or whatever that goes up and down to sight on the night’s target. OK, the Hubble doesn’t have a dome and it uses gyros but even there you’ve got to point it. How does IceCube point?”

“It doesn’t. The targets point themselves.”

“Huh?”

“Ever relayed a Web-page?”

“Sure.”

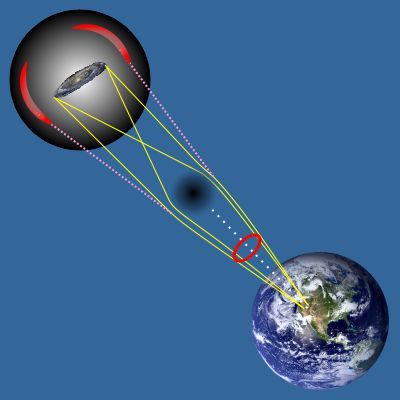

“Guess what? You don’t know where the page came from, you don’t know where it’s going to end up. But it could carry a tracking bug to tell someone at some call-home server when and where the page had been opened. IceCube works the same way, sort of. It has a huge 3D array of detectors to record particles coming in from any direction. A neutrino can come from above, below, any side, no problem — the detectors it touches will signal its path.”

“How huge?”

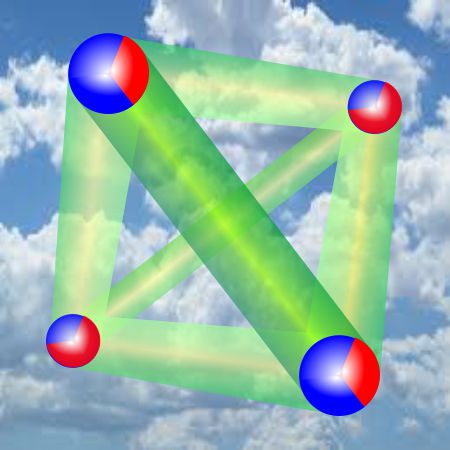

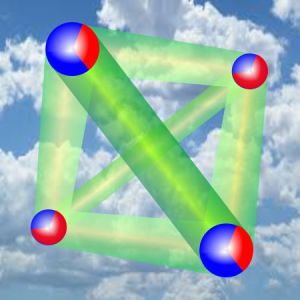

“Vastly huge. The instrument is basically a cubic kilometer of ultra-clear Antarctic ice that’s ages old. The equivalent of the tracking bugs is 5000 sensors in a honeycomb array more than a kilometer wide. Every hexagon vertex marks a vertical string of sensors going down 2½ kilometers into the ice. Each string has a couple of sensors near the surface but the rest of them are deeper than 1½ kilometers. The sensors are looking for flashes of light. Keep track of which sensor registered a flash when and you know the path a particle took through the array.”

“Why should there be flashes? I thought neutrinos didn’t interact with matter.”

“Why should there be flashes? I thought neutrinos didn’t interact with matter.”

“Make that, they rarely interact with matter. Even that depends on what particle the neutrino encounters and what flavor neutrino it happens to be at the moment.”

That gets both Al and me interested. His “Neutrinos come in flavors?” overlaps my “At the moment?”

“I thought that would get you into this, Sy. Early experiments detected only 1/3 of the neutrinos we expected to come from the Sun. Unwinding all that was worth four Nobel prizes and counting. The upshot’s that there are three different neutrino flavors and they mutate. The experiments caught only one.”

Vinnie’s standing behind us. “You’re going to tell us the flavors, right?”

“Hoy, Vinnie, Jeremy’s question was first, and it bears on the others. Jeremy, you know that blue glow you see around water-cooled nuclear fuel rods?”

“Yeah, looks spooky. That’s neutrinos?”

“No, that’s mostly electrons, but it could be other charged particles. It has to do with exceeding the speed of light in the medium.”

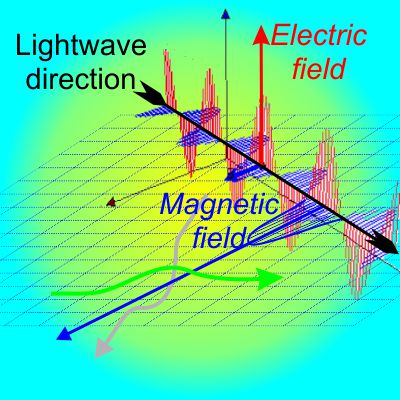

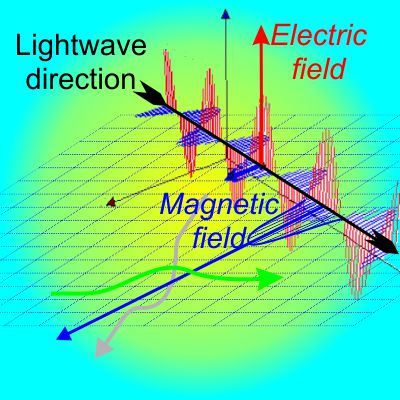

“Hey, me and Sy talked about that. A lightwave makes local electrons wiggle, and how fast the wiggles move forward can be different from how fast the wave group moves. Einstein’s speed-of-light thing was about the wave group’s speed, right, Sy?”

“That’s right, Vinnie.”

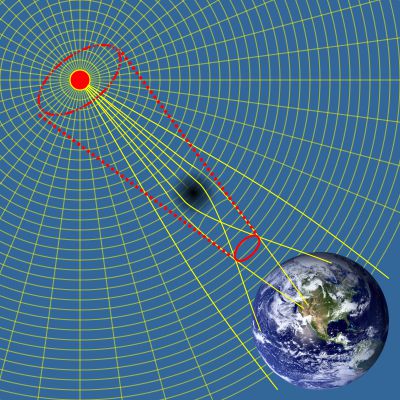

“So anyhow, Jeremy, a moving charged particle affects the local electromagnetic field. If the particle moves faster than the surrounding atoms can adjust, that generates light, a conical electromagnetic wave with a continuous spectrum. The light’s called Cherenkov radiation and it’s mostly in the ultra-violet, but enough leaks down to the visible range that we see it as blue.”

“But you said it takes a charged particle. Neutrinos aren’t charged. So how do the flashes happen in IceCube?”

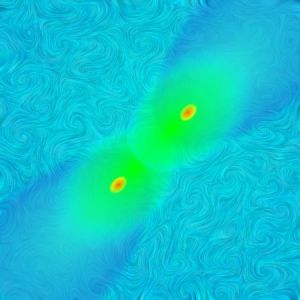

“Suppose an incoming high-energy neutrino transfers some of its momentum to a charged particle in the ice — flash! Even better, the flash pattern provides information for distinguishing between the neutrino flavors. Muon neutrinos generate a more sharp-edged Cherenkov cone than electron neutrinos do. Taus are so short-lived that IceCube doesn’t even see them.”

“I suppose muon and tau are flavors?”

“Indeed, Vinnie. Any subatomic reaction that releases an electron also emits an electron-flavored neutrino. If the reaction releases the electron’s heavier cousin, a muon, then you get a muon-flavored neutrino. Taus are even heavier and they’ve got their own associated neutrino.”

“And they mutate?”

“In a particularly weird way.”

~~ Rich Olcott

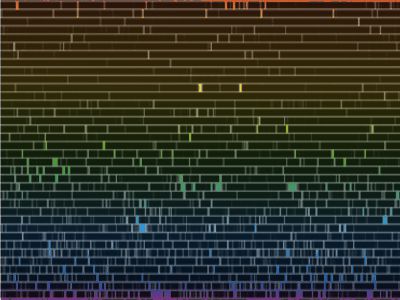

“You’re right, Sy. It’s not a particularly pretty picture, but it shows that nice strong sodium doublet in the yellow and the broad iron and hydrogen lines down in the green and blue. I’ll admit it, Vinnie, this is a faked image I made to show my students what the solar atmosphere would look like if you could turn off the photosphere’s continuous blast of light. The point is that the atoms emit exactly the same sets of colors that they absorb.”

“You’re right, Sy. It’s not a particularly pretty picture, but it shows that nice strong sodium doublet in the yellow and the broad iron and hydrogen lines down in the green and blue. I’ll admit it, Vinnie, this is a faked image I made to show my students what the solar atmosphere would look like if you could turn off the photosphere’s continuous blast of light. The point is that the atoms emit exactly the same sets of colors that they absorb.”

“Infinite?”

“Infinite?”