A crisp Fall day, perfect for a brisk walk around the park. I see why the geese are huddled at the center of the lake — Mr Feder, not their best friend, is on patrol again. Then he spots me. “Hey, Moire, I gotta question!”

“Of course you do, Mr Feder. What is it?”

“Some guy on TV said Einstein proved gravity goes at the speed of light and if the Sun suddenly went away it’d take eight minutes before we went flying off into space. Did Einstein really say that? Why’d he say that? Was the TV guy right? And what would us flying across space feel like?”

“I’ll say this, Mr Feder, you’re true to form. Let’s see… Einstein didn’t quite prove it, the TV fellow was right, and we’d notice being cold and in the dark well before we’d notice we’d left orbit. As to why, that’s a longer story. Walk along with me.”

“Okay, but not too fast. What’s not quite about Einstein’s proving?”

“Physicists like proofs that use dependable mathematical methods to get from experimentally-tested principles, like conservation of energy, to some result they can trust. We’ve been that way since Galileo used experiments to overturn Aristotle’s pure‑thought methodology. When Einstein linked gravity to light the linkage was more like poetry. Beautiful poetry, though.”

“What’s so beautiful about something like that?”

“All the rhymes, Mr Feder, all the rhymes. Both gravity and light get less intense with the square of the distance. Gravity and light have the same kinds of symmetries—”

“What the heck does that mean?”

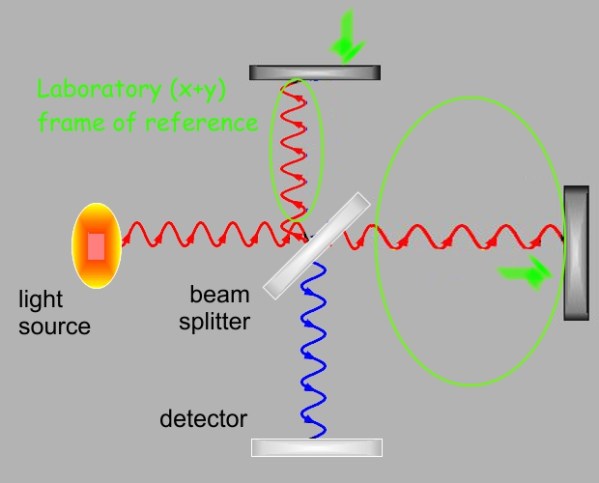

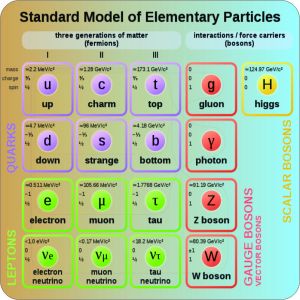

“If an object or system has symmetry, you can execute certain operations on it yet make no apparent difference. Rotate a square by 90° and it looks just the same. Gravity and light both have spherical symmetry. At a given distance from a source, the field intensity’s the same no matter what direction you are from the source. Because of other symmetries they both obey conservation of momentum and conservation of energy. In the late 1890s researchers found Lorentz symmetry in Maxwell’s equations governing light’s behavior.”

“You’re gonna have to explain that Lorentz thing.”

“Lorentz symmetry has to do with phenomena an observer sees near an object when their speed relative to the object approaches some threshold. Einstein’s Special Relativity theory predicted that gravity would also have Lorentz symmetry. Observations showed he was right.”

“So they both do Lorentz stuff. That makes them the same?”

“Oh, no, completely different physics but they share the same underlying structure. Maxwell’s equations say that light’s threshold is lightspeed.”

“Gravity does lightspeed, too, I suppose.”

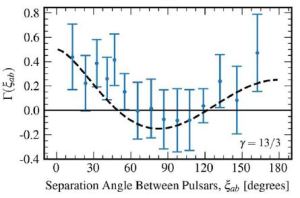

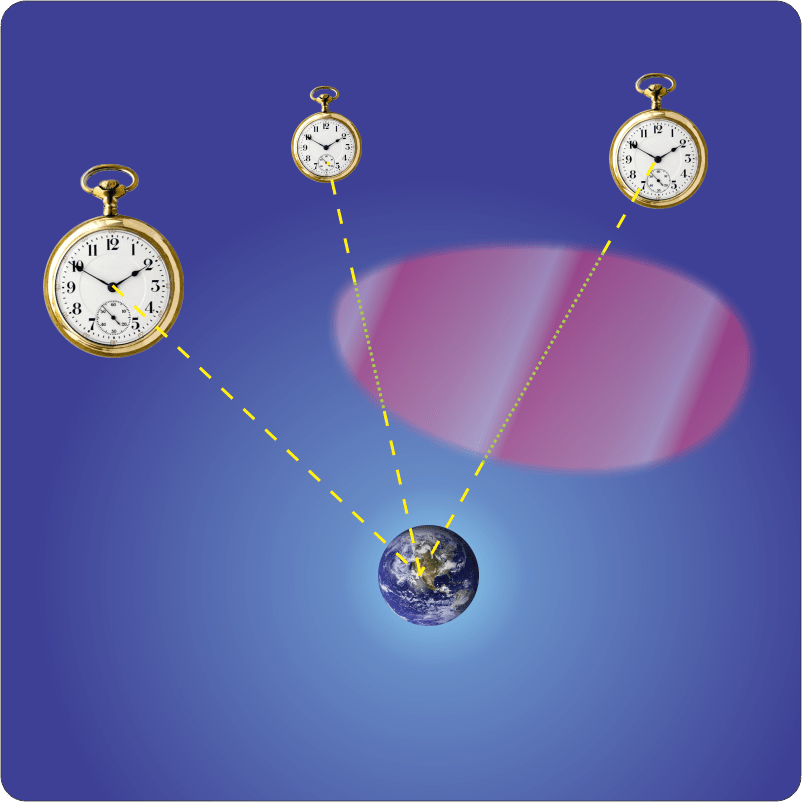

“There were arguments about that. Einstein said beauty demands that both use the same threshold. Other people said, ‘Prove it.’ The strongest argument in his favor at the time was rough, indirect, complicated, and had to do with fine details of Earth’s orbit around the Sun. Half a century later pulsar timing data gave us an improved measurement, still indirect and complicated. This one showed gravity’s threshold to be with 0.2% of lightspeed.”

“Anything direct like I could understand it?”

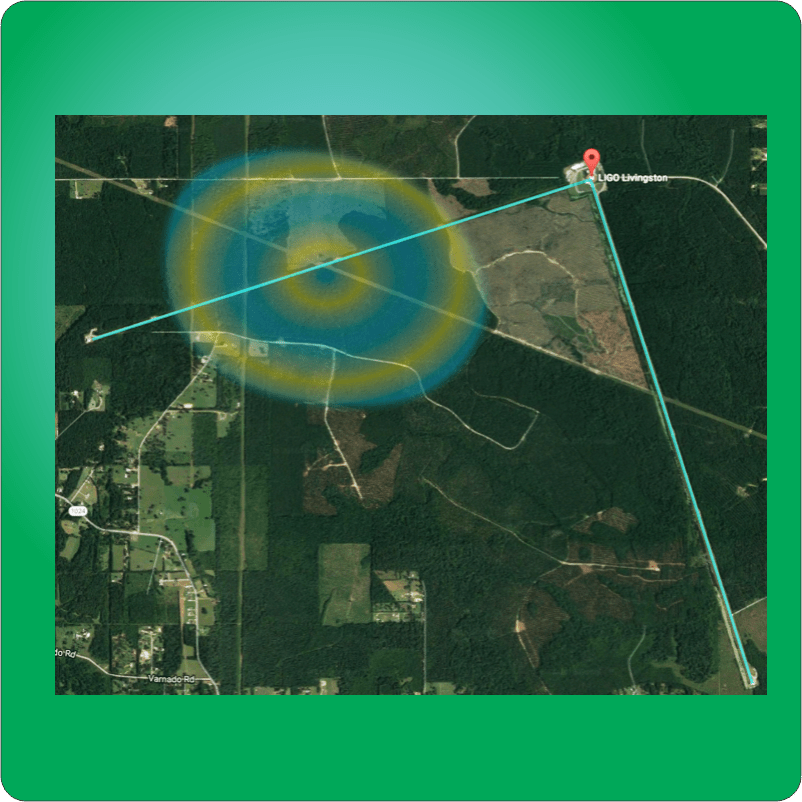

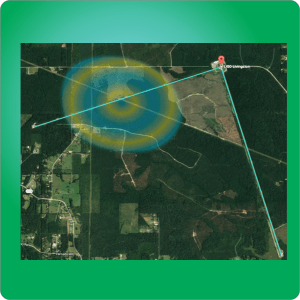

“How about a straight‑up horse race? In 2017, the LIGO facility picked up a gravitational signal that came in at the same time that optical and gamma ray observatories recorded pulses from the same source, a colliding pair of neutron stars in a galaxy 130 million lightyears away. A long track, right?”

“Waves, not horses, but how far apart were the signals?”

“Close enough that the measured speed of gravity is within 10–15 of the speed of light.”

“A photo-finish.”

“Nice pun, Mr Feder. We’re about 8½ light-minutes away from the Sun so we’re also 8½ gravity-minutes from the Sun. As the TV announcer said, if the Sun were to suddenly dematerialize then Earth would lose the Sun’s orbital attraction 8½ minutes later. We as individuals wouldn’t go floating off into space, though. Earth’s gravity would still hold us close as the whole darkened, cooling planet leaves orbit and heads outward.”

“I like it better staying close to home.”

~ Rich Olcott

“Gravitational waves are relativity effects and neutrinos are quantum mechanical. Physicists have been struggling for a century to bridge those two domains. Evidence from a three-messenger event could provide the final clues.”

“Gravitational waves are relativity effects and neutrinos are quantum mechanical. Physicists have been struggling for a century to bridge those two domains. Evidence from a three-messenger event could provide the final clues.”

“OK,

“OK,

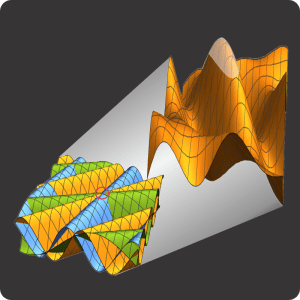

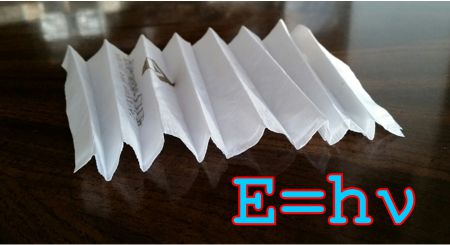

I smoothed out one of Vinnie’s crumpled napkins. As I folded it into pleats and scooted it along the table I said, “Doesn’t mess up the wave so much as change the way we think about it. We’re used to graphing out a spatial wave as an up-and-down pattern like this that moves through time, right?”

I smoothed out one of Vinnie’s crumpled napkins. As I folded it into pleats and scooted it along the table I said, “Doesn’t mess up the wave so much as change the way we think about it. We’re used to graphing out a spatial wave as an up-and-down pattern like this that moves through time, right?”