Stepping into Pizza Eddie’s I see Jeremy at his post behind the gelato stand, an impressively thick book in front of him. “Hi, Jeremy, one chocolate-hazelnut combo, please. What’re you reading there?”

“Hi, Mr Moire. It’s Moby Dick, for English class.”

“Ah, one of my favorites. Melville was a 19th-century techie, did for whaling what Tom Clancy did for submarines.”

“You’re here at just the right time, Mr Moire. I’m reading the part where something called ‘the corpusants’ are making lights glow around the Pequod. Sometimes he calls them lightning, but they don’t seem to come down from the sky like real lightning. Umm, here it is, he says. ‘All the yard-arms were tipped with pallid fire, and touched at each tri-pointed lightning-rod-end with three tapering white flames, each of the three tall masts was silently burning in that sulphurous air, like three gigantic wax tapers before an altar.’ What’s that about?”

“That glow is also called ‘St Elmo’s Fire‘ among other things. It’s often associated with a lightning storm but it’s a completely different phenomenon. Strictly speaking it’s a concentrated coronal discharge.”

“That doesn’t explain much, sir.”

“Take it one word at a time. If you pump a lot of electrons into a confined space, they repel each other and sooner or later they’ll find ways to leak away. That’s literally dis-charging.”

“How do you ‘pump electrons’?”

“Oh, lots of ways. The ancient Greeks did it by rubbing amber with fur, Volta did it chemically with metals and acid, Van de Graaff did it with a conveyor belt, Earth does it with winds that transport air between atmospheric layers. You do it every time you shuffle across a carpet and get shocked when you put your finger near a water pipe or a light switch.”

“That only happens in the wintertime.”

“Actually, carpet-shuffle electron-pumping happens all the time. In the summer you discharge as quickly as you gain charge because the air’s humidity gives the electrons an easy pathway away from you. In the winter you’re better insulated and retain the charge until it’s too late.”

“Hm. Next word.”

“Corona, like ‘halo.’ A coronal discharge is the glow you see around an object that gets charged-up past a certain threshold. In air the glow can be blue or purple, but you can get different colors from other gases. Basically, the electric field is so intense that it overwhelms the electronic structure of the surrounding atoms and molecules. The glow is electrons radiating as they return to their normal confined chaos after having been pulled into some stretched-out configuration.”

“But this picture of the corpusants has them just at the mast-heads and yard-arms, not all over the boat.”

“That’s where the ‘concentrated’ word come in. I puzzled over that, too, when I first looked into the phenomenon. Made no sense.”

“Yeah. If the electrons are repelling each other they ought to spread out as much as possible. So why do they seem pour out of the pointy parts?”

“That was a mystery until the 1880s when Heaviside cleaned up Maxwell’s original set of equations. The clarified math showed that the key is the electric field’s spread-out-ness, technically known as divergence.”

With my finger I draw in the frost on his gelato cabinet. “Imagine this is a brass ball, except I’ve pulled one side of it out to a cone. Someone’s loaded it up with extra electrons so it’s carrying a high negative charge.”

With my finger I draw in the frost on his gelato cabinet. “Imagine this is a brass ball, except I’ve pulled one side of it out to a cone. Someone’s loaded it up with extra electrons so it’s carrying a high negative charge.”

“The electrons have spread themselves evenly over the metal surface, right, including at the pointy part?”

“Yup, that’s why I’m doing my best to make all these electric field arrows the same distance apart at their base. They’re also supposed to be perpendicular to the surface. What part of that field will put the most rip-apart stress on the local air molecules?”

“Oh, at the tip, where the field spreads out most abruptly.”

“Bingo. What makes the glow isn’t the average field strength, it’s how drastically the field varies from one side of a molecule to the other. That’s what rips them apart. And you get the greatest divergence at the pointy parts like at the Pequod’s mast-head.”

“And Ahab’s harpoon.”

~~ Rich Olcott

Jennie’s turn — “Didn’t the chemists define away a whole lot of entropy when they said that pure elements have zero entropy at absolute zero temperature?”

Jennie’s turn — “Didn’t the chemists define away a whole lot of entropy when they said that pure elements have zero entropy at absolute zero temperature?”

“That’s not quite what I said, Jennie. Old Reliable’s software and and I worked up a hollow-shell model and to my surprise it’s consistent with one of Stephen Hawking’s results. That’s a long way from saying that’s what a black hole is.”

“That’s not quite what I said, Jennie. Old Reliable’s software and and I worked up a hollow-shell model and to my surprise it’s consistent with one of Stephen Hawking’s results. That’s a long way from saying that’s what a black hole is.” My notes say D is the black hole’s diameter and d is another object’s distance from its center. One second in the falling object’s frame would look like f seconds to us. But one mile would look like 1/f miles. The event horizon is where d equals the half-diameter and f goes infinite. The formula only works where the object stays outside the horizon.”

My notes say D is the black hole’s diameter and d is another object’s distance from its center. One second in the falling object’s frame would look like f seconds to us. But one mile would look like 1/f miles. The event horizon is where d equals the half-diameter and f goes infinite. The formula only works where the object stays outside the horizon.” “Wow, Old Reliable looks up stuff and takes care of unit conversions automatically?”

“Wow, Old Reliable looks up stuff and takes care of unit conversions automatically?”

“Wait, Mr Moire, we said that the event horizon’s just a mathematical construct,

“Wait, Mr Moire, we said that the event horizon’s just a mathematical construct,

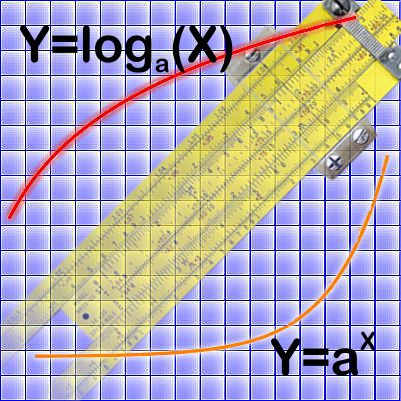

“Good. Now copy A1:A7 by value into C1:C7 and generate a scatter plot of B1:C7. This time apply the logarithmic scale to the y-axis. This’ll show us how often we’d need to compound to get the yield on the x-axis.”

“Good. Now copy A1:A7 by value into C1:C7 and generate a scatter plot of B1:C7. This time apply the logarithmic scale to the y-axis. This’ll show us how often we’d need to compound to get the yield on the x-axis.”

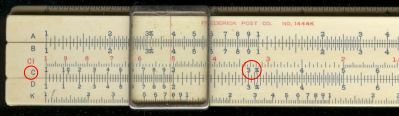

“Look for 3.16 on there. You read it like a ruler — the number before the decimal point shows as a digit, then you locate the fractional part with the high and low vertical lines.”

“Look for 3.16 on there. You read it like a ruler — the number before the decimal point shows as a digit, then you locate the fractional part with the high and low vertical lines.”