<further along our story arc…> “Want a refill?”

“No, I’ve had enough. But I could go for some dessert.”

“Nothing here in the office, care for some gelato?”

We take the elevator down to Eddie’s on 2. Things are slow. Jeremy’s doing homework behind the gelato display. Eddie’s at the checkout counter, rolling some dice. He gives the eye to her white satin. “You’ll fit right in when the theater crowd gets here, Miss. Don’t know about you, Sy.”

“Fitting in’s not my thing, Eddie. This is my client, Anne. What’s with the bones?”

“Weirdest thing, Sy. I’m getting set up for the game after closing (don’t tell nobody, OK?) but these dice gotta be bad somehow. I roll just one, I get every number, but when I roll the two together I get nothin’ but snake-eyes and boxcars.”

I shoot Anne a look. She shrugs. I sing out, “Hey, Jeremy, my usual chocolate-hazelnut combo. For the lady … I’d say vanilla and mint.”

She shoots me a look. “How’d you know?”

I shrug. “Lucky guess. It’s a good evening for the elephant.”

“Hey, no livestock in here, Sy, the Health Department would throw a fit!”

“It’s an abstract elephant, Eddie. Anne and I’ve been discussing entropy. Which is an elephant because it’s got so many aspects no-one can agree on what it is.”

“So it’s got to do with luck?”

“With counting possibilities. Suppose you know something happened, but there’s lots of ways it could have happened. You don’t know which one it was. Entropy is a way to measure what’s left to know.”

“Like what?”

“Those dice are an easy example. You throw the pair, they land in any of 36 different ways, but you don’t know which until you look, right?”

“Yeah, sure. So?”

“So your uncertainty number is 36. Suppose they show 7. There’s still half-a-dozen ways that can happen — first die shows 6, second shows 1, or maybe the first die has the 1 and the second has the 6, and so on. You don’t know which way it happened. Your uncertainty number’s gone down from 36 to 6.”

“Wait, but I do know something going in. It’s a lot more likely they’ll show a 7 than snake-eyes.”

“Good point, but you’re talking probability, the ratio of uncertainty numbers. Half-a-dozen ways to show a 7, divided by 36 ways total, means that 7 comes up seventeen throws out of a hundred. Three times out of a hundred you’ll get snake-eyes. Same odds for boxcars.”

“C’mon, Sy, in my neighborhood little babies know those odds.”

“But do the babies know how odds combine? If you care about one event OR another you add the odds, like 6 times out of a hundred you get snake-eyes OR boxcars. But if you’re looking at one event AND another one the odds multiply. How often did you roll those dice just now?”

“Couple of dozen, I guess.”

“Let’s start with three. Suppose you got snake-eyes AND you got snake-eyes AND you got snake-eyes. Odds on that would be 3×3×3 out of 100×100×100 or 27 out of a million triple-throws. Getting snake-eyes or boxcars 24 times in a row, that’s … ummm … less than one chance in a million trillion trillion sets of 24-throws. Not likely.”

“Don’t know about the numbers, Sy, but there’s something goofy with these dice.”

Anne cuts in. “Maybe not, Eddie. Unusual things do happen. Let me try.” She gets half-a-dozen 7s in a row, each time a different way. “Now you try,” and gives him back the dice. Now he rolls an 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 in order. “They’re not loaded. You’re just living in a low-probability world.”

“Aw, geez.”

“Anyway, Eddie, entropy is a measure of residual possibilities — alternate conditions (like those ways to 7) that give identical results. Suppose a physicist is working on a system with a defined number of possible states. If there’s some way to calculate their probabilities, they can be plugged into a well-known formula for calculating the system’s entropy. The remarkable thing, Anne, is that what you calculate from the formula matches up with the heat capacity entropy.”

“Here’s your gelato, Mr Moire. Sorry for the delay, but Jennie dropped by and we got to talking.”

Anne and I trade looks. “That’s OK, Jeremy, I know how that works.”

~~ Rich Olcott

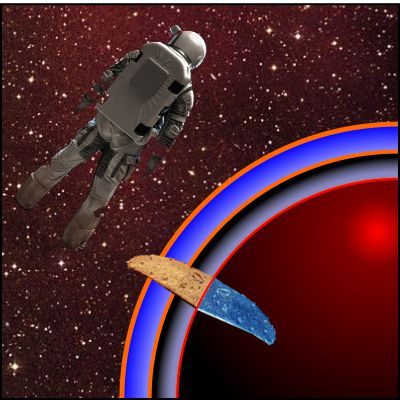

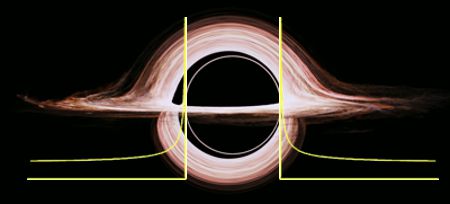

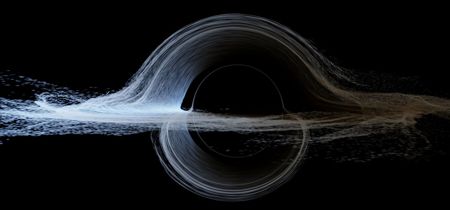

, where D is the object’s diameter and d is your distance from it. Suppose the Sun suddenly collapsed without losing any mass to become a Schwarzchild object. The object’s diameter would be a bit less than 4 miles. Earth is 93 million miles from the Sun so the compression factor here would be [poking numbers into my smartphone] 1.000_000_04. Nothing you’d notice. It’d be 1.000_000_10 at Mercury. You wouldn’t see even 1% compression until you got as close as 378 miles, 10% only inside of 43 miles. Fifty percent of the effect shows up in the last 13 miles. The edge of a black hole is sharper than this pizza knife.”

, where D is the object’s diameter and d is your distance from it. Suppose the Sun suddenly collapsed without losing any mass to become a Schwarzchild object. The object’s diameter would be a bit less than 4 miles. Earth is 93 million miles from the Sun so the compression factor here would be [poking numbers into my smartphone] 1.000_000_04. Nothing you’d notice. It’d be 1.000_000_10 at Mercury. You wouldn’t see even 1% compression until you got as close as 378 miles, 10% only inside of 43 miles. Fifty percent of the effect shows up in the last 13 miles. The edge of a black hole is sharper than this pizza knife.”

. A is proportional to spin. When A is small (not much spin) or the distance is large those A/d² terms essentially vanish relative to the others and the scaling looks just like the simple almost-a-point Schwarzchild case. When A is large or the distance is small the A/d² terms dominate top and bottom, the factor equals 1 and there’s dragging but no compression. In the middle, things get interesting and that’s where Dr Thorne played.”

. A is proportional to spin. When A is small (not much spin) or the distance is large those A/d² terms essentially vanish relative to the others and the scaling looks just like the simple almost-a-point Schwarzchild case. When A is large or the distance is small the A/d² terms dominate top and bottom, the factor equals 1 and there’s dragging but no compression. In the middle, things get interesting and that’s where Dr Thorne played.”

“A few. The most important for this discussion is energy and time.”

“A few. The most important for this discussion is energy and time.”