It was a classic May day, perfect for some time by the lake in the park. I was watching the geese when a squadron of runners stampeded by. One of them broke stride, dashed my way and plopped down on the bench beside me. “Hi, Mr Moire. <pant, pant>”

“Afternoon, Jeremy. How are things?”

“Moving along, sir. I’ve signed up for track, I think it’ll help my base-running, I’ve met a new girl, she’s British, and that virtual particle stuff is cool but I’m having trouble fitting it into my black hole paper.”

“Here’s one angle. Nobelist Gerard ‘t Hooft said, ‘A particle is fundamental when it’s useful to think of it as fundamental.‘ In that sense, a black hole is a fundamental particle. Even more elementary than atoms, come to think of it.”

“Huh?”

“It has to do with the how few numbers you need to completely specify the particle. You’d need a gazillion terabytes for just the temperatures in the interior and oceans and atmosphere of Earth. But if you’re making a complete description of an isolated atom you just need about two dozen numbers — three for position, three for linear momentum, one for atomic number (to identify which element it represents), one for its atomic weight (which isotope), one for its net charge if it’s been ionized, four more for nuclear and electronic spin states, maybe three or four each for the energy levels of its nuclear and electronic configuration. So an atom is simpler than the Earth”

“And for a black hole?”

“Even simpler. A black hole’s event horizon is smooth, so smooth that you can’t distinguish one point from another. Therefore, no geography numbers. Furthermore, the physics we know about says whatever’s inside that horizon is completely sealed off from the rest of the universe. We can’t have knowledge of the contents, so we can’t use any numbers to describe it. It’s been proven (well, almost proven) that a black hole can be completely specified with only eleven numbers — one for its total mass-energy, one for its electric charge, and three each for position, linear momentum and angular momentum. Leave out the location and orientation information and you’ve got three numbers — mass, charge, and spin. That’s it.”

“How about its size or it temperature?”

“Depends how you measure size. Event horizons are spherical or nearly so, but the equations say the distance from an event horizon to where you’d think its center should be is literally infinite. You can’t quantify a horizon’s radius, but its diameter and surface area are both well-defined. You can calculate both of them from the mass. That goes for the temperature, too.”

“How about if it came from antimatter instead of matter?”

“Makes no difference because the gravitational stresses just tear atoms apart.”

“Wait, you said, ‘almost proven.’ What’s that about?”

“Believe it or not, the proof is called The No-hair Theorem. The ‘almost’ has to do with the proof’s starting assumptions. In the simplest case, zero change and zero spin and nothing else in the Universe, you’ve got a Schwarzchild object. The theorem’s been rigorously proven for that case — the event horizon must be perfectly spherical with no irregularities — ‘no hair’ as one balding physicist put it.”

“How about if the object spins and gets charged up, or how about if a planet or star or something falls into it?”

“Adding non-zero spin and charge makes it a Kerr-Newman object. The theorem’s been rigorously proven for those, too. Even an individual infalling mass has only a temporary effect. The black hole might experience transient wrinkling but we’re guaranteed that the energy will either be radiated away as a gravitational pulse or else simply absorbed to make the object a little bigger. Either way the event horizon goes smooth and hairless.”

“So where’s the ‘almost’ come in?”

“Reality. The region near a real black hole is cluttered with other stuff. You’ve seen artwork showing an accretion disk looking like Saturn’s rings around a black hole. The material in the disk distorts what would otherwise be a spherical gravitational field. That gnarly field’s too hairy for rigorous proofs, so far. And then Hawking pointed out the particle fuzz…”

~~ Rich Olcott

“OK,

“OK,

This video, from an Orbits Table display at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, shows a different Plutonian weirdness. We’re circling the Solar System at about 50 times Earth’s distance from the Sun (50 AU). Reading inward, the white lines represent the orbits of Neptune, Uranus, Saturn and Jupiter. The Asteroid Belt is the small greenish ring close to the Sun. The four terrestrial planets are even further in. The Kuiper Belt is the greenish ring that encloses the lot.

This video, from an Orbits Table display at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, shows a different Plutonian weirdness. We’re circling the Solar System at about 50 times Earth’s distance from the Sun (50 AU). Reading inward, the white lines represent the orbits of Neptune, Uranus, Saturn and Jupiter. The Asteroid Belt is the small greenish ring close to the Sun. The four terrestrial planets are even further in. The Kuiper Belt is the greenish ring that encloses the lot.

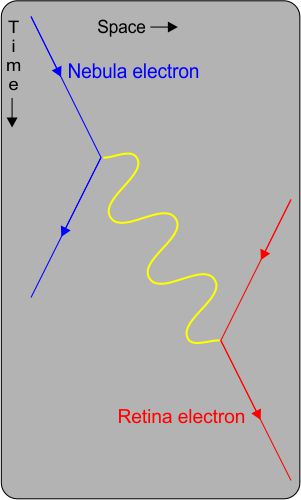

Here we have a Feynman diagram, named for the Nobel-winning (1965) physicist who invented it and much else. The diagram plots out the transaction we just discussed. Not a conventional x-y plot, it shows Space, Time and particles. To the left, that far-away electron emits a photon signified by the yellow wiggly line. The photon has momentum so the electron must recoil away from it.

Here we have a Feynman diagram, named for the Nobel-winning (1965) physicist who invented it and much else. The diagram plots out the transaction we just discussed. Not a conventional x-y plot, it shows Space, Time and particles. To the left, that far-away electron emits a photon signified by the yellow wiggly line. The photon has momentum so the electron must recoil away from it.

It would have been awesome to watch Dragon Princes in battle (from a safe hiding place), but I’d almost rather have witnessed “The Tussles in Brussels,” the two most prominent confrontations between Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr.

It would have been awesome to watch Dragon Princes in battle (from a safe hiding place), but I’d almost rather have witnessed “The Tussles in Brussels,” the two most prominent confrontations between Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr. Like Newton, Einstein was a particle guy. He based his famous thought experiments on what his intuition told him about how particles would behave in a given situation. That intuition and that orientation led him to paradoxes such as entanglement, the

Like Newton, Einstein was a particle guy. He based his famous thought experiments on what his intuition told him about how particles would behave in a given situation. That intuition and that orientation led him to paradoxes such as entanglement, the  Bohr was six years younger than Einstein. Both Bohr and Einstein had attained Directorship of an Institute at age 35, but Bohr’s has his name on it. He started out as a particle guy — his first splash was a trio of papers that treated the hydrogen atom like a one-planet solar system. But that model ran into serious difficulties for many-electron atoms so Bohr switched his allegiance from particles to Schrödinger’s wave theory. Solve a Schrödinger equation and you can calculate statistics like

Bohr was six years younger than Einstein. Both Bohr and Einstein had attained Directorship of an Institute at age 35, but Bohr’s has his name on it. He started out as a particle guy — his first splash was a trio of papers that treated the hydrogen atom like a one-planet solar system. But that model ran into serious difficulties for many-electron atoms so Bohr switched his allegiance from particles to Schrödinger’s wave theory. Solve a Schrödinger equation and you can calculate statistics like  Here’s where Ludwig Wittgenstein may have come into the picture. Wittgenstein is famous for his telegraphically opaque writing style and for the fact that he spent much of his later life disagreeing with his earlier writings. His 1921 book, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (in German despite the Latin title) was a primary impetus to the Logical Positivist school of philosophy. I’m stripping out much detail here, but the book’s long-lasting impact on QM may have come from its Proposition 7: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.“

Here’s where Ludwig Wittgenstein may have come into the picture. Wittgenstein is famous for his telegraphically opaque writing style and for the fact that he spent much of his later life disagreeing with his earlier writings. His 1921 book, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (in German despite the Latin title) was a primary impetus to the Logical Positivist school of philosophy. I’m stripping out much detail here, but the book’s long-lasting impact on QM may have come from its Proposition 7: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.“

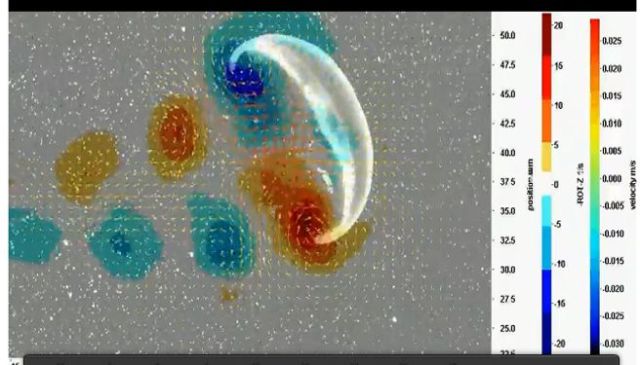

Grammie always grimaced when Grampie lit up one of his cigars inside the house. We kids grinned though because he’d soon be blowing smoke rings for us. Great fun to try poking a finger into the center, but we quickly learned that the ring itself vanished if we touched it.

Grammie always grimaced when Grampie lit up one of his cigars inside the house. We kids grinned though because he’d soon be blowing smoke rings for us. Great fun to try poking a finger into the center, but we quickly learned that the ring itself vanished if we touched it.

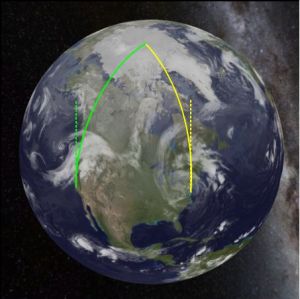

For instance, suppose Fred and Ethel collaborate on a narwhale research project. Fred is based in San Diego CA and Ethel works out of Norfolk VA. They fly to meet their research vessel at the North Pole. Fred’s plane follows the green track, Ethel’s plane follows the yellow one. At the start of the trip, they’re on parallel paths going straight north (the dotted lines). After a few hours, though, Ethel notices the two planes pulling closer together.

For instance, suppose Fred and Ethel collaborate on a narwhale research project. Fred is based in San Diego CA and Ethel works out of Norfolk VA. They fly to meet their research vessel at the North Pole. Fred’s plane follows the green track, Ethel’s plane follows the yellow one. At the start of the trip, they’re on parallel paths going straight north (the dotted lines). After a few hours, though, Ethel notices the two planes pulling closer together.

The line rotates as a unit — every skater completes a 360o rotation in the same time. Similarly, everywhere on Earth a day lasts for exactly 24 hours.

The line rotates as a unit — every skater completes a 360o rotation in the same time. Similarly, everywhere on Earth a day lasts for exactly 24 hours. Now suppose our speedy skater hits a slushy patch of ice. Her end of the line is slowed down, so what happens to the rest of the line? It deforms — there’s a new center of rotation that forces the entire line to curl around towards the slow spot. Similarly, that blob near the Equator in the split-Earth diagram curls in the direction of the slower-moving air to its north, which is counter-clockwise.

Now suppose our speedy skater hits a slushy patch of ice. Her end of the line is slowed down, so what happens to the rest of the line? It deforms — there’s a new center of rotation that forces the entire line to curl around towards the slow spot. Similarly, that blob near the Equator in the split-Earth diagram curls in the direction of the slower-moving air to its north, which is counter-clockwise.

It all started with Newton’s mechanics, his study of how objects affect the motion of other objects. His vocabulary list included words like force, momentum, velocity, acceleration, mass, …, all concepts that seem familiar to us but which Newton either originated or fundamentally re-defined. As time went on, other thinkers added more terms like power, energy and action.

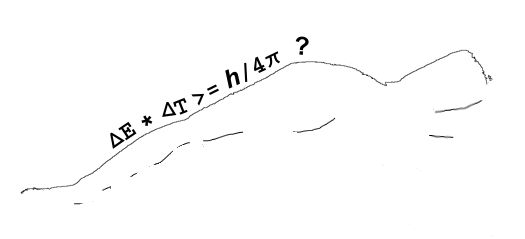

It all started with Newton’s mechanics, his study of how objects affect the motion of other objects. His vocabulary list included words like force, momentum, velocity, acceleration, mass, …, all concepts that seem familiar to us but which Newton either originated or fundamentally re-defined. As time went on, other thinkers added more terms like power, energy and action. There is another way to get the same dimension expression but things aren’t not as nice there as they look at first glance. Action is given by the amount of energy expended in a given time interval, times the length of that interval. If you take the product of energy and time the dimensions work out as (ML2/T2)*T = ML2/T, just like Heisenberg’s Area.

There is another way to get the same dimension expression but things aren’t not as nice there as they look at first glance. Action is given by the amount of energy expended in a given time interval, times the length of that interval. If you take the product of energy and time the dimensions work out as (ML2/T2)*T = ML2/T, just like Heisenberg’s Area.