“What’re the odds?”

“Odds on what, Vinnie?”

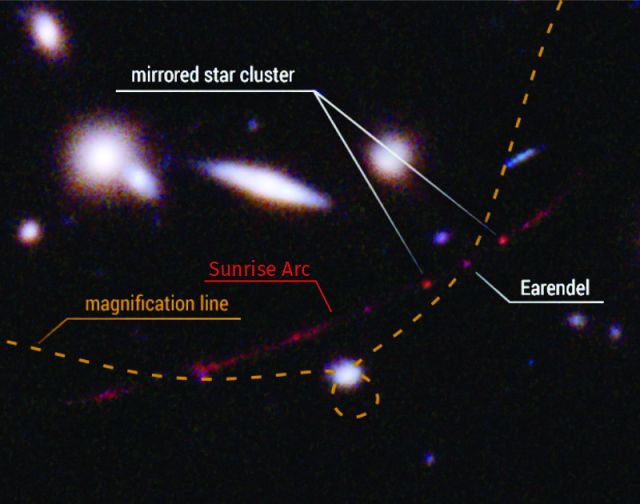

“A gazillion galaxies out there, only 41 lensing galaxy clusters, but one of them shows us a singleton star. I mean, what’s special about that star? What are the odds?”

I can’t help it. “Astronomical, Vinnie.”

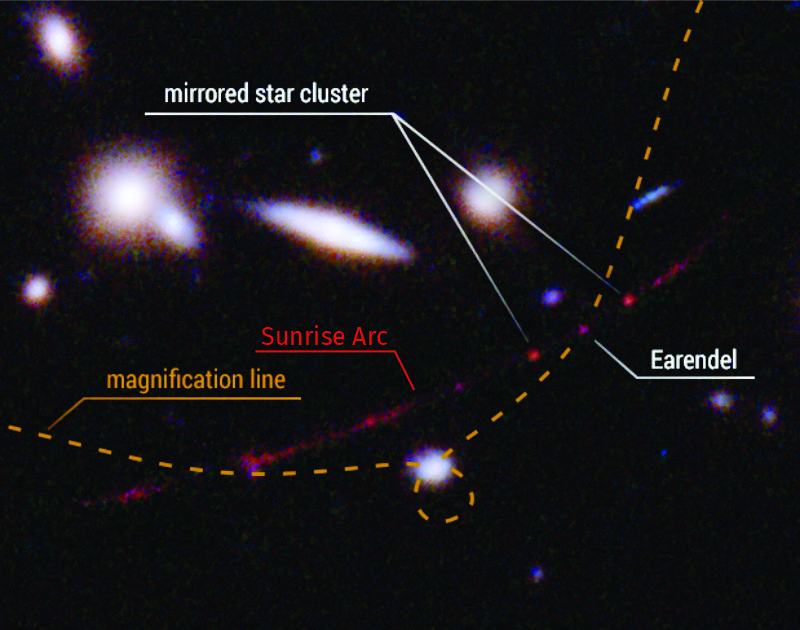

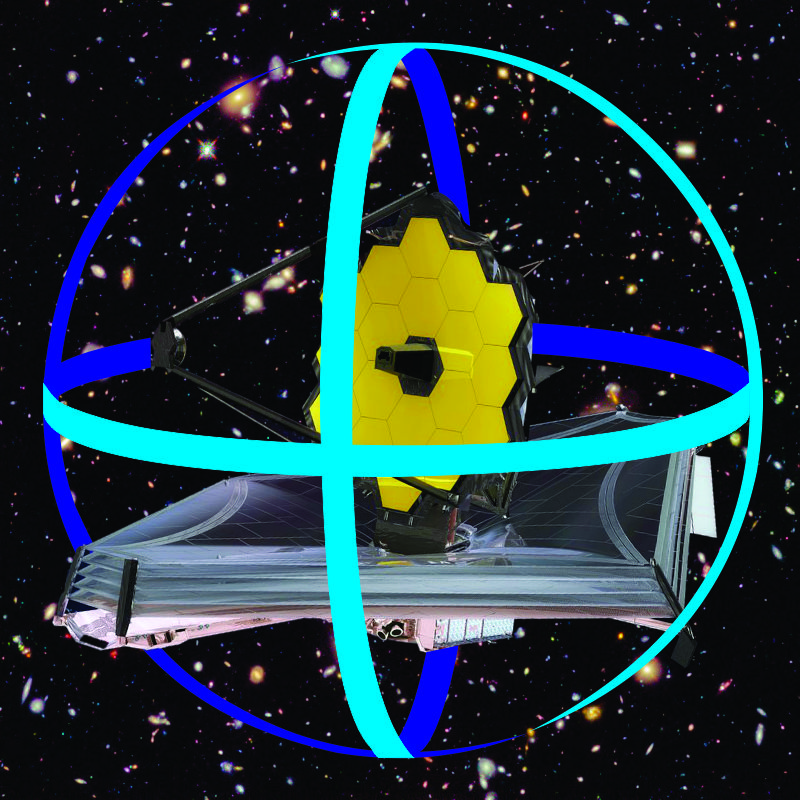

Cathleen punches my shoulder, hard. “Sy Moire, you be ashamed of yourself. That pun was ancient a century ago. Vinnie, the odds are better than they seem. We didn’t just stumble on Earendel and the Sunrise Arc, we found them in a highly targeted Big Data search for things just like that — objects whose light was extremely stretched and also gravitationally bent in our direction. The Arc’s lensing galaxy cluster has a spherical effect, more or less, so it also acts on light from other far-away objects and sends it in other directions. It even bends an image of our Milky Way towards Earendel’s galaxy.”

“I call weaseling — you used ‘more or less‘.”

“Guilty as charged, Vinnie. A nice, spherical black hole is the simplest case of gravitational lensing — just one mass at the center of its simple light‑bending gravity field. Same thing for a single star like our Sun. Clusters are messy. Tens or hundreds of billion‑star galaxies, scattered at random angles and random positions about their common center of mass. The combined gravity field is lumpy, to say the least. Half of that research paper is devoted to techniques for estimating the field and its effects on light in the region around the Arc.”

“I guess they had to get 3D positions for all the galaxies in the cluster. That’d be a lot of work.”

“It would, Al, but that’s beyond what current technology can do. Instead, they used computer models to do — get this, Sy — curve fitting.”

<chuckle> “Good one, Cathleen.”

“What’s so funny?”

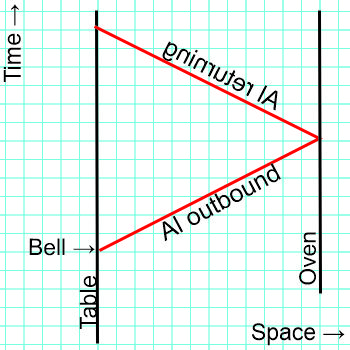

“There’s a well-established scientific technique called ‘curve fitting.’ You graph some data and try to find an equation that does a respectable job of running through or at least near your data points. Newton started it, of course. Putting it in modern terms, he’d plot out some artillery data and say, ‘Hmm, that looks like a parabola H=h+v·t+a·t2. I wonder what values of h, v and a make the H-t curve fit those measurements. Hey, a is always 32 feet per second per second. Cool.’ Or something like that. Anyhow, Cathleen’s joke was that the researchers used curve fitting to fit the Sunrise Arc’s curve, right?”

“They did that, Sy. The underlying physical model, something called ‘caustic optics,’ says that—”

“Caustic like caustic soda? I got burnt by that stuff once.”

under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license

“That’s the old name for sodium hydroxide, Vinnie. It’s a powerful chemical and yeah, it can give you trouble if you’re not careful. That name and caustic optics both come from the Greek word for burning. The optics term goes back to using a lens as a burning glass. See those focused patterns of light next to your water glass? Each pattern is a caustic. The Arc’s lensing cluster’s like any light‑bender, it’s enclosed in a caustic perimeter. Light passing near the perimeter gets split, the two parts going to either side of the perimeter. The Earendel team’s curve‑fitting project asked, ‘Where must the caustic perimeter be to produce these duplicate galaxy images neighboring the Arc?‘ The model even has that bulge from the gravity of a nearby foreground galaxy.”

“And the star?”

“Earendel seems to be smack on top of the perimeter. Any image touching that special line is intensified way beyond what it ought to be given the source’s distance from us. It’s a pretty bright star to begin with, though. Or maybe two stars.”

“Wait, you don’t know?”

“Not yet. This study pushed the boundaries of what Hubble can do for us. We’re going to need JWST‘s infrared instruments to nail things down.”

Al’s in awe. “Wow — that caustic’s sharp enough to pick one star out of a galaxy.”

“Beat the astronomical odds, huh?”

Credit: Science: NASA / ESA / Brian Welch (JHU) / Dan Coe (STScI); Image processing: NASA / ESA / Alyssa Pagan (STScI)

~~ Rich Olcott