Vinnie’s never been a patient man. “We’re still waiting, Sy. What’s the time-cause-effect thing got to do with black holes and information?”

“You’ve got most of the pieces, Vinnie. Put ’em together yourself.”

“Geez, I gotta think? Lessee, what do I know about black holes? Way down inside there’s a huge mass in a teeny singularity space. Gravity’s so intense that relativity theory and quantum mechanics both give up. That can’t be it. Maybe the disk and jets? No, ’cause some holes don’t have them, I think. Gotta be the Event Horizon which is where stuff can’t get out from. How’m I doing, Sy?”

“You’re on the right track. Keep going.”

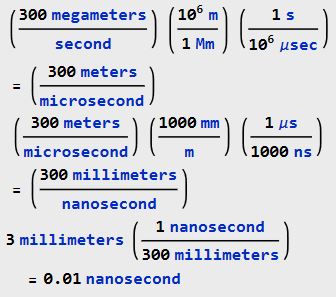

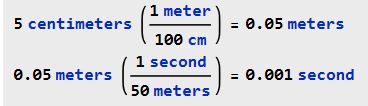

“Okay, so we just talked about how mass scrambles spacetime, tilts the time axis down to point towards where mass is so axes stop being perpendicular and if you’re near a mass then time moves you even closer to it unless you push away and that’s how gravity works. That’s part of it, right?”

“As rain. So mass and gravity affect time, then what?”

“Ah, Einstein said that cause‑and‑effect runs parallel with time ’cause you can’t have an effect before what caused it. You’re saying that if gravity tilts time, it’ll tilt cause‑and‑effect?”

“So far as we know.”

“That’s a little weasel-ish.”

“Can’t help it. The time‑directed flow of causality is a basic assumption looking for counter‑examples. No‑one’s come up with a good one, though there’s a huge literature of dubious testimonials. Something called a ‘closed timelike curve‘ shows up in some solutions to Einstein’s equations for extreme conditions like near or inside a black hole. Not a practical concern at our present stage of technology — black holes are out of reach and the solutions depend on weird things like matter with negative mass. So anyhow, what happens to causality where gravity tilts time?”

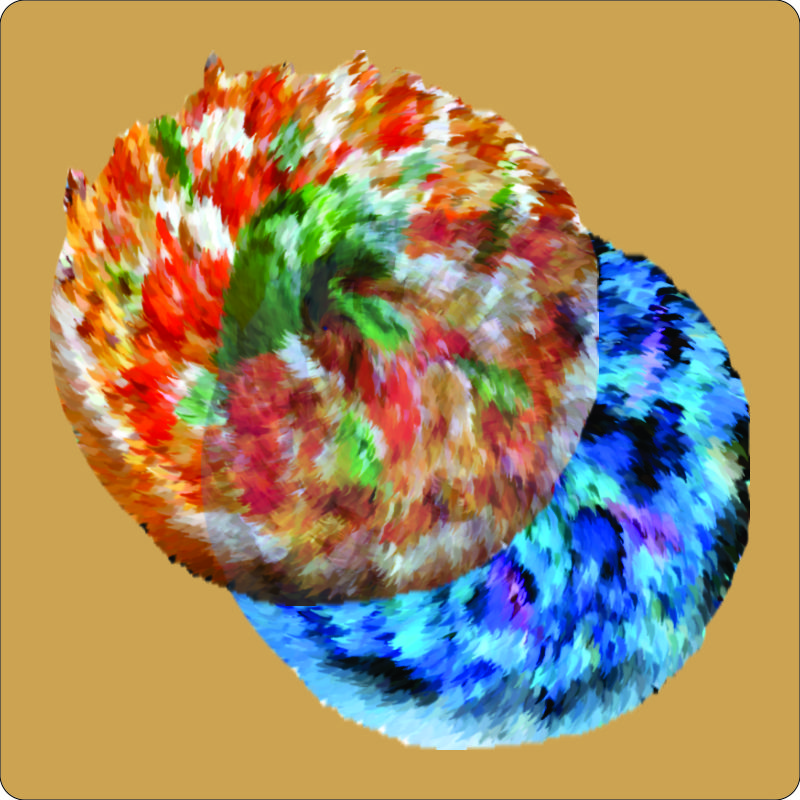

“I see where you’re going. If time’s tilted toward the singularity inside a black hole, than so is cause‑and‑effect. Nothing in there can cause something to happen outside. Hey, bring up that OVR graphics app on Old Reliable, I’ll draw you a picture.”

“Sure.”

“See, way out in space here this circle’s a frame where time, that’s the red line, is perpendicular to the space dimensions, that’s the black line, but it’s way out in space so there’s no gravity and the black line ain’t pointing anywhere in particular. Red line goes from cause in the middle to effect out beyond somewhere. Then inside the black hole here’s a second frame. Its black line is pointing to where the mass is and time is tilted that way too and nothing’s getting away from there.”

“Great. Now add one more frame right on the border of your black hole. Make the black line still point toward the singularity but make the red line tangent to the circle.”

“Like this?”

“Perfect. Now why’d we put it there?”

“You’re saying that somewhere between cause-effect going wherever and cause-effect only going deeper into the black hole there’s a sweet spot where it doesn’t do either?”

“Exactly, and that somewhere is the Event Horizon. Suppose we’re in a mothership and you’re in our shuttlecraft in normal space. You fire off a skyrocket. Both spacecraft see sparks going in every direction. If you dive below an Event Horizon and fire another skyrocket, in your frame you’d see a normal starburst display. If we could check that from the mothership frame, we’d see all the sparks headed inward but we can’t because they’re all headed inward. All the sparkly effects take place closer in.”

“How about lighting a firework on the Horizon?”

“Good luck with that. Mathematically at least, the boundary is infinitely thin.”

“So bottom line, light’s trapped inside the black hole because time doesn’t let the photons have an effect further outward than they started. Do I have that right?”

“For sure. In fact, you can even think of the hole as an infinite number of concentric shells, each carrying a causality sign reading ‘Abandon hope, all ye who enter here‘. So what’s that say about information?”

“Hah, we’re finally there. Got it. Information can generate effects. If time can trap cause‑effect, then it can trap information, too.”

~~ Rich Olcott