“Any other broad-brush Jupiter averages, Cathleen?”

“How about chemistry, Vinnie? Big picture, 84% of Jupiter’s atoms are hydrogen, 16% are helium.”

“Doesn’t leave much room for asteroids and such that fall in.”

“Less than a percent for all other elements. Helium doesn’t do chemistry, so from a distant chemist’s perspective Jupiter and Saturn both look like a dilute hydrogen‑helium solution of every other element. But the solvent’s not a typical laboratory liquid.”

“Hard to think of a gas as a solvent.”

“True, Sy, but chemistry gets strange under high temperatures and pressures.”

“Hey, I always figured Jupiter to be cold ’cause it’s farther from the Sun than us.”

“Good logic, Vinnie, but Jupiter generates its own heat. That’s one reason its weather is different from ours. Earth gets more than 99% of its energy budget from sunlight, especially in the infrared. There’s year‑long solar heating at low latitudes but only half‑years of that near the Poles. The imbalance is behind the temperature disparities that drive our prevailing weather patterns.”

“Jupiter’s not like that?”

“Nope. It gets 30 times less energy from the Sun than Earth does and actually gives off more heat than it receives. Its poles and equator are at virtually the same chilly temperature. There’s a small amount of heat flow from equator to poles, but most of Jupiter’s heat migrates spherically from a 24,000 K fever near its core to its outer layers.”

“What could generate all that heat?”

“Probably several contributors. The dominant one is gravitational potential energy from everything falling inward and banging into everything else. Random rock or atom collisions generate heat. Entropy rules.”

“Sounds reasonable. What’s another?”

“Radioactives. Half of Earth’s internal heating comes from gravity, same mechanism as Jupiter though on a smaller scale. The rest comes from unstable isotopes like uranium, thorium and potassium‑40. Also aluminum‑26, back in the early years, but that’s all gone now. Jupiter undoubtedly ate from the same dinner table. Those fissionable atoms split and release heat whenever they feel like it whether or not they’re collected in one place like in a reactor or bomb. Whatever the origin, Jupiter ferries that heat to the surface and dumps it as infrared radiation.”

“Yeah or else it’d explode or something.”

“Mm-hm. The question is, what are the heat‑carrying channels? They must thread their way through the planet’s structure.”

“It’s just a big ball of gas, how can it have structure?”

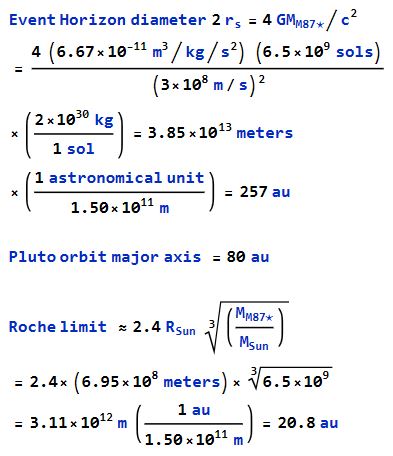

“I can help with that, Vinnie. Remember a few years back I wrote about high‑pressure chemistry? Hydrogen gets weird at a million bars‑‑‑”

“Anyone’d get weird after that many bars, Sy.” <heh, heh>

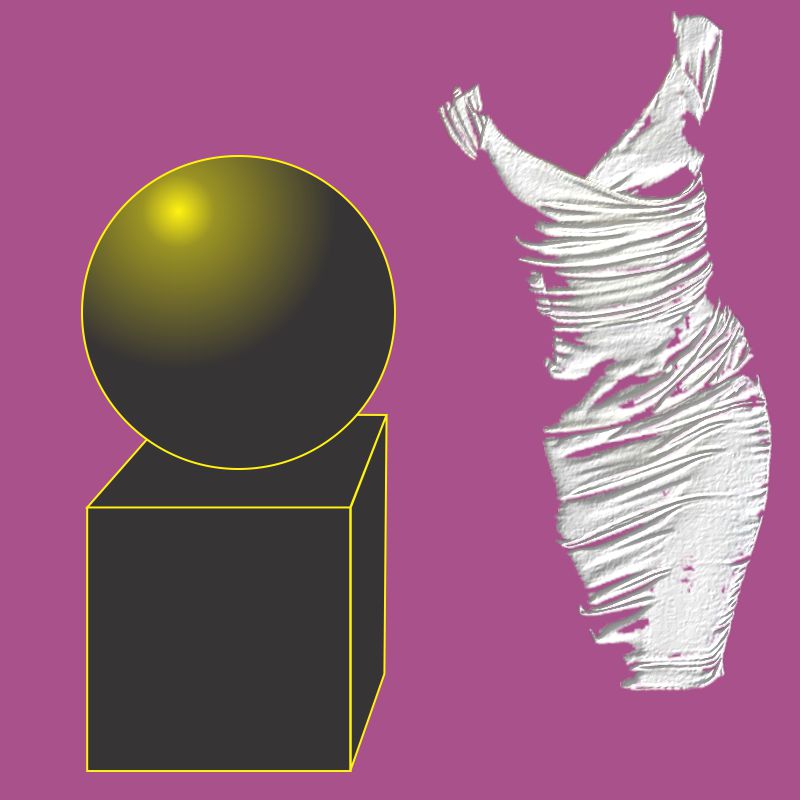

“Ha ha, Vinnie. A bar is pressure equal to one Earth atmosphere. Pressures deep inside Jupiter get into hundreds of megabars. Hydrogen molecules down there are crammed so close together that their electron clouds merge and you have a collection of protons floating in a sea of electron charge. They call it metallic hydrogen, but it’s fluid like mercury, not crystalline. Cathleen, when you refer to Jupiter’s structure you’re thinking layers?”

“That’s right, Sy, but the layers may or may not be arranged like Earth’s crust, mantle, core scheme. A lot of the Juno data is consistent with that — a shell of the atmosphere we see, surrounding a thick layer of increasingly compressed hydrogen‑helium over a core of heavy stuff suspended in metallic hydrogen. About 20% down we think the helium is squeezed out and falls like rain, only to evaporate again at a lower level. The core’s metallic hydrogen may even be solid despite thousand‑degree temperatures — we just don’t know how hydrogen behaves in that regime.”

“What other kind of layering can there be?”

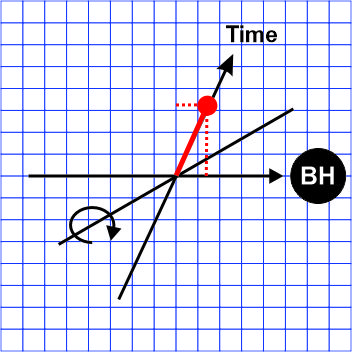

“Experiments have demonstrated that under the right conditions a rapidly spinning fluid can self-organize into a series of concentric rotating cylinders. Maybe Jupiter and the other gas planets follow that model and the stripes show where the cylinders intersect with gravity’s spherical imperative. Coaxial cylinders would account for the equator and poles rotating at different rates. Juno data indicates that Jupiter’s equatorial zone has more ammonia than the rest of its atmosphere. Maybe between‑cylinder winds trap the ammonia and prevent it from mixing with the next deeper cylinder.”

~ Rich Olcott