<chirp chirp> “Moire here.”

“Hi, Sy, it’s Susan Kim. I read your humidifier piece and I’ve got your answer for you.”

“Answer? I didn’t know I’d asked a question.”

“Sure you did. You worked out that your humidifier mostly keeps your office at 45% relative humidity by moisturizing incoming air that’s a lot drier than that. As a chemist I like how you brought in moles to check your numbers. Anyway, you wondered how to figure the incoming airflow. I’ve got your answer. It’s a scaling problem.”

“Mineral scaling? No, I don’t think so. The unit’s mostly white plastic so I wouldn’t see any scaling, but it seems to be working fine. I’ve been using de-ionized water and following the instructions to rinse the tank with vinegar every week or so.”

“Nope, not that kind of scale, Sy. You’ve got a good estimate from a small sample and you wondered how to scale it up, is all.”

“Sample? How’d I take a sample?”

“You gave us the numbers. Your office is 1200 cubic feet, right, and it took 88 milliliters of water to raise the relative humidity to where you wanted it, right, and the humidifier used a 1000 milliliters of water to keep it there for a day, right? Well, then. If one roomful of air requires 88 milliliters, then a thousand milliliters would humidify (1000/88)=11.4 room changes per day.”

“Is that a good number?”

“I knew you’d ask. According to the ventilation guidelines I looked up, ‘Buildings occupied by people typically need between 5 and 10 cubic feet per minute per person of fresh air ventilation.‘ You’re getting 11.4 roomfuls per day, times your office volume of 1200 cubic feet, divided by 1440 minutes per day. That comes to 9.5 cubic feet per minute. On the button if you’re alone, a little bit shy if you’ve got a client or somebody in there. I’d say your building’s architect did a pretty good job.”

“I like the place, except for when the elevators act up. All that figuring must have you thirsty. Meet me at Al’s and I’ll buy you a mocha latte.”

“Sounds like a plan.”

“Hi, folks. Saw you coming so I drew your usuals, mocha latte for Susan, black mud for Sy. Did I guess right?”

“Al, you make mocha lattes better than anybody.”

“Thanks, Susan, I do my best. Go on, take a table.”

“Susan, I was thinking while I walked over here. My cousin Crystal doesn’t like to wear those N95 virus masks because she says they make her short of breath. Her theory is that they trap her exhaled CO2 and those molecules get in the way of the O2 molecules she wants to breathe in. What does chemistry say to that theory?”

“Hmm. Well, we can make some estimates. N95 filtration is designed to block 95% of all particles larger than 300 nanometers. A couple thousand CO2 molecules could march abreast through a mesh opening that size no problem. An O2 molecule is about the same size. Both kinds are so small they never contact the mesh material so there’s essentially zero likelihood of differential effect.”

“So exhaled CO2 isn’t preferentially concentrated. Good. How about the crowd‑out idea?”

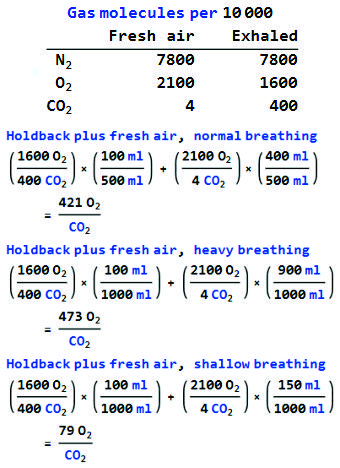

“Give me a second. <tapping on phone> Not supported by the numbers, Sy. There’s one CO2 for every 525 O2‘s in fresh air. Exhaled air is poorer in O2, richer in CO2, but even there oxygen has a 4‑to‑1 dominance.”

“But if the mask traps exhaled air…”

“Right. The key number is the retention ratio, what fraction of an exhaled breath the mask holds back. A typical exhale runs about 500 milliliters, could be half that if you’ve got lung trouble, twice or more if you’re working hard. This mask looks about 300 milliliters just sitting on the table, but there’s probably only 100 milliliters of space when I’m wearing it. It’s just arithmetic to get the O2/CO2 ratio for each breathing mode, see?”

“Looks good.”

“Even a shallow breather still gets 79 times more O2 than CO2. Blocking just doesn’t happen.”

“I’ll tell Crys.”

~ Rich Olcott