<chirp, chirp> “Moire here.”

“Hi, Sy, it’s Susan.”

“Well, hello. Good to hear from you. What’s up?”

“I’m out here on my back porch, fooling around on my laptop. It’s too nice to work in the lab today.”

“I agree with you. I’m outside, too, enjoying the Springtime. What’s your fooling around?”

“I found a discovery date list for all the chemical elements. Guess which element was the first that humanity worked with in pure form?”

“Mmm, I’d say carbon, in charcoal.”

“Nope, it’s copper.”

“Copper?”

“Mm-hm. Or maybe gold. They both occur as the raw metal but copper’s more common. There was a Copper Age before the Bronze age. The dates are fuzzy because they depend on what the archaeologists find after site scavengers have been there. I’m sending you the first few rows from the list.

| Cumulative Count | Element (Symbol) | Atomic number | Estimated years ago |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Copper (Cu) | 29 | 10000 |

| 2 | Lead (Pb) | 82 | 6000 |

| 3 | Carbon (C) | 6 | 5750 |

| 4 | Silver (Ag) | 47 | 5000 |

| 5 | Tin (Sn) | 50 | 5000 |

| 6 | Antimony (Sb) | 51 | 5000 |

| 7 | Gold (Au) | 79 | 4500 |

| 8 | Iron (Fe) | 26 | 4000 |

| 9 | Mercury (Hg) | 80 | 3500 |

| 10 | Sulfur (S) | 16 | 2500 |

“You can win most of them from the right ore with relatively simple processing. It makes sense they’re the ones we got to first.”

“Susan, I’m surprised it took a thousand years to realize you can get sulfur from cinnabar ore at the same time you’re cooking the mercury out of it. I wouldn’t want to be downwind from that process or most of the rest.”

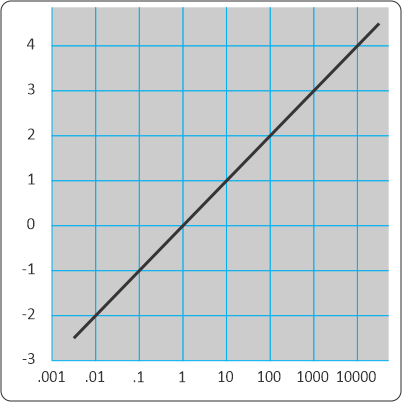

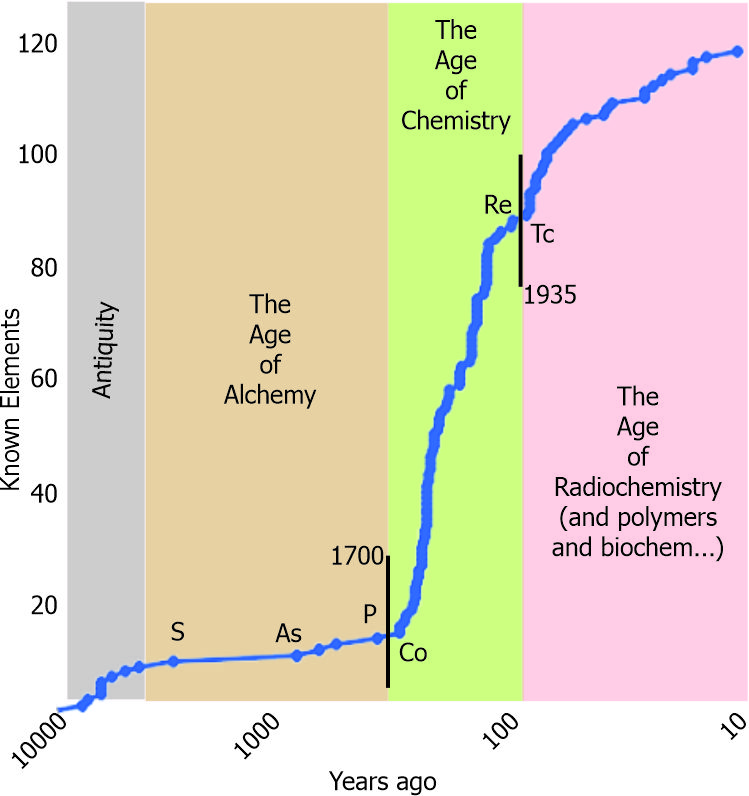

“Sure not. I’ll bet there just wasn’t much interest in sulfur until the alchemists started playing with it. Anyhow, I dumped the element data into a spreadsheet and got some fun facts when I graphed it. Look at this. Eight thousand years for 10 elements through sulfur, then 1800 years of nothing. Arsenic doesn’t show up until the Thirteenth Century when I guess royalty started using it to poison each other. And phosphorus — have you read Neal Stephenson’s Baroque Cycle trilogy?”

“Yes, and I know the episode you’re thinking of, where the hero routed a gang at night by coating himself with glowing phosphorus and bursting out of a cave pretending to be a demon. Stephenson put a lot of words into describing how factories obtained mercury and phosphorus back then.”

“Stephenson puts a lot of words into most everything nerdy. That’s why I enjoy reading him. Oh-ho, now I know how you knew about cinnabar being the source for mercury.”

“Hey, Susan, I don’t only do Physics, but yeah, that was from another Baroque Cycle episode. … Looking at your graph here — things certainly took off at the start of the Eighteenth Century.”

“Yes, indeed. Seventy-four elements, everything that’s not radioactive plus a couple that are. I get a chuckle from cobalt being the first element in that wave after phosphorus. You know the story?”

“What story is that?”

“Seventeenth Century miners kept digging up nasty rocks that emitted poisonous gas when smelted along with the desirable copper and nickel ores. They called the bad stuff kobald Oren, German for ‘goblin ores.’ When a Swedish chemist finally purified the material he simply re-spelled the adjective and called the metal cobalt. I love the linkage with Stephenson’s fictional phosphorus-covered demon.”

“Cute. Why the break between rhenium and technitium?”

“That second wave after 1935 is all radioactives. Funny how the timing paralleled Seaborg’s research career even though he never got involved with technitium, the first artificially-produced element. Imagine being the discoverer of ten different elements.”

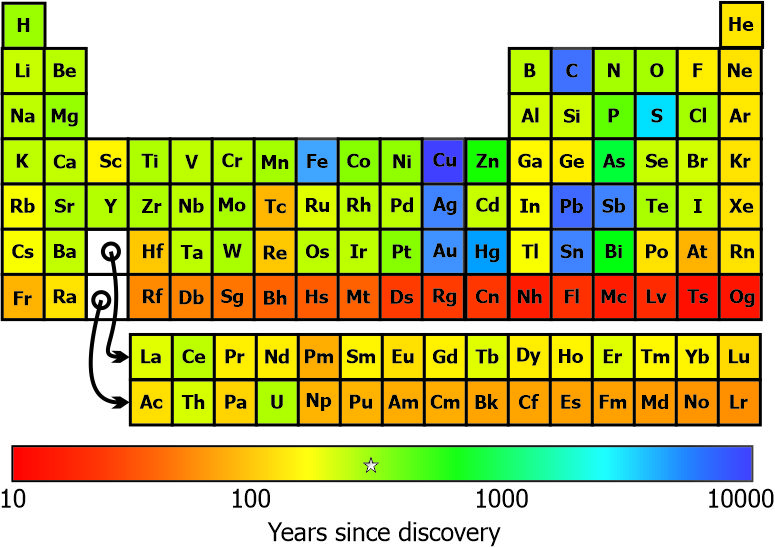

“Seaborg practically invented that funny bottom row of the Periodic Table, didn’t he?”

“Oh, yes. Not only did he discover or co-discover more than half of those elements, he was the one who proposed setting off the entire group as Actinides, in parallel with the Lanthanides above them. Oh, that reminds me, I meant to show you the other display I built. You’ve probably never seen one like this.”

“Whoa, you’ve colored each element block by how long we’ve known about it. That’s not the kind of thing you can do with crayons.”

“No, I had to do some programming to get the right tints.”

“What’s the little star for in the middle of the scale?”

“That’s when Mendeleev first proposed the Table, smack in the logarithmic center of my timeline. Don’t you love it?”

~~ Rich Olcott