Teena’s next dash is for the slide, the high one, of course. “Ha-ha, Uncle Sy, beat you here. Look at me climbing up and getting potential energy!”

“You certainly did and you certainly are.”

“Now I’m sliding down all kinetic energy, wheee!” <thump, followed by thoughtful pause> “Uncle Sy, I’m all mixed up. You said momentum and energy are like cousins and we can’t create or destroy either one but I just started momentum coming down and then it stopped and where did my kinetic energy go? Did I break Mr Newton’s rule?”

“My goodness, those are good questions. They had physicists stumped for hundreds of years. You didn’t break Mr Newton’s Conservation of Momentum rule, you just did something his rule doesn’t cover. I did say there are important exceptions, remember.”

“Yeah, but you didn’t say what they are.”

“And you want to know, eh? Mmm, one exception is that the objects have to be big enough to see. Really tiny things follow quantum rules that have something like momentum but it’s different. Uhh, another exception is the objects can’t be moving too fast, like near the speed of light. But for us the most important exception is that the rule only applies when all the energy to make things move comes from objects that are already moving.”

“Like my marbles banging into each other on the floor?”

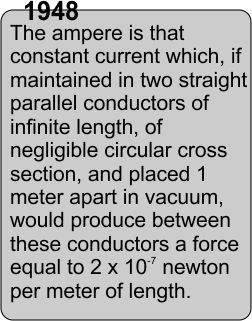

“An excellent example. Mr Newton was starting a new way of doing science. He had to work with very simple systems and and so his rules were very simple. One Sun and one planet, or one or two marbles rolling on a flat floor. His rules were all about forces and momentum, which is a combination of mass and speed. He said the only way to change something’s momentum was to push it with a force. Suppose when you push on a marble it goes a foot in one second and has a certain momentum. If you push it twice as hard it goes two feet in one second and has twice the momentum.”

“What if I’ve got a bigger marble?”

“If you have a marble that’s twice as heavy and you give it the one-foot-per-second speed, it has twice the momentum. Once there’s a certain amount of momentum in one of Mr Newton’s simple systems, that’s that.”

“Oh, that’s why I’ve got to snap my steelie harder than the glass marbles ’cause it’s heavier. Oh!Oh!And when it hits a glass one, that goes faster than the steelie did ’cause it’s lighter but it gets the momentum that the steelie had.”

“Perfect. You Mommie will be so proud of you for that thinking.”

“Yay! So how are momentum and energy cousins?”

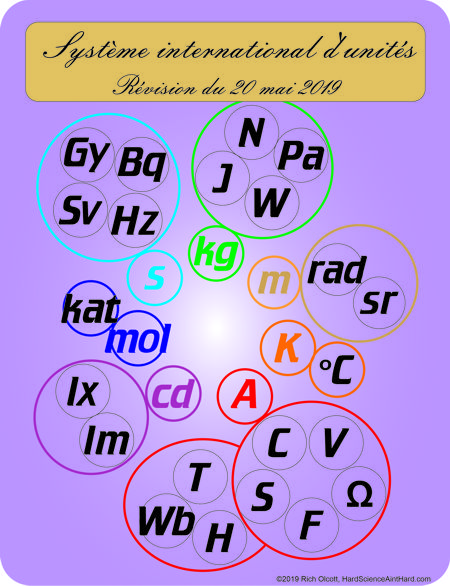

“Cous… Oh. What I said was they’re related. Both momentum and kinetic energy depend on both mass and speed, but in different ways. If you double something’s speed you give it twice the momentum but four times the amount of kinetic energy. The thing is, there’s only a few kinds of momentum but there are lots of kinds of energy. Mr Newton’s Conservation of Momentum rule is limited to only certain situations but the Conservation of Energy rule works everywhere.”

“Energy is bigger than momentum?”

“That’s one way of putting it. Let’s say the idea of energy is bigger. You can get electrical energy from generators or batteries, chemical energy from your muscles, gravitational energy from, um, gravity –“

“Atomic energy from atoms, wind energy from the wind, solar energy from the Sun –“

“Cloud energy from clouds –“

“Wait, what?”

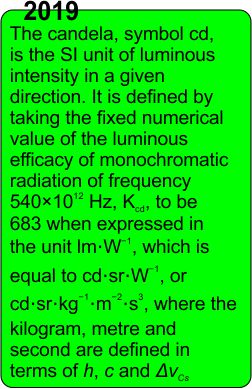

“Just kidding. The point is that energy comes in many varieties and they can be converted into one another and the total amount of energy never changes.”

“Then what happened to my kinetic energy coming down the slide? I didn’t give energy to anything else to make it start moving.”

“Didn’t you notice the seat of your pants getting hotter while you were slowing down? Heat is energy, too — atoms and molecules just bouncing around in place. In fact, one of the really good rules is that sooner or later, every kind of energy turns into heat.”

“Big me moving little atoms around?”

“Lots and lots of them.”

~~ Rich Olcott