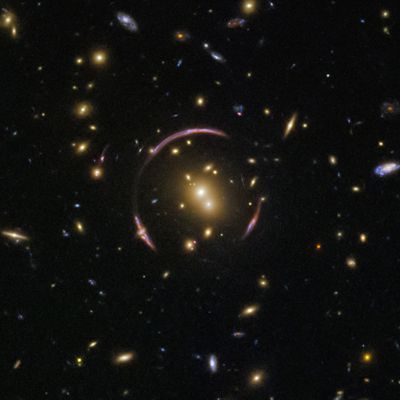

Cathleen and I are at a table in Al’s coffee shop, discussing not much, when Vinnie comes barreling in. “Hey, guys. Glad I found you together. I just saw this ‘Einstein ring’ photo. They say it’s some kind of lensing phenomenon and I’m thinking that a lens floating out in space to do that has to be yuuuge. What’s it made of, and d’ya think aliens put it there to send us a message?”

Astronomer Cathleen rises to the bait. I sit back to watch the fun. “No, Vinnie, I don’t. We’re not that special, the rings aren’t signals, and the lenses aren’t things, at least not in the way you’re thinking.”

“There’s more than one?”

“Hundreds we know of so far and it’s early days because the technology’s still improving.”

“How come so many?”

“It’s because of what makes the phenomenon happen. What do you know about gravity and light rays?”

“Me and Sy talked about that a while ago. Light rays think they travel in straight lines past a heavy object, but if you’re watching the beam from somewhere else you think it bends there.”

I chip in. “Nice summary, good to know you’re storing this stuff away.”

“Hey, Sy, it’s why I ask questions is to catch up. So go on, Cathleen.”

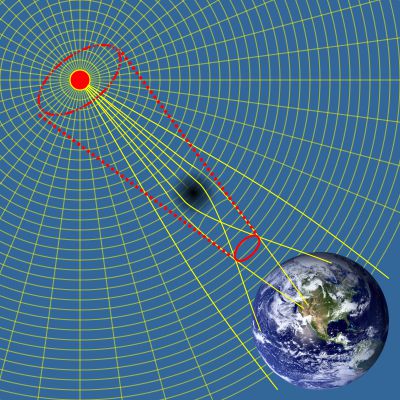

She swings her laptop around to show us a graphic. “So think about a star far, far away. It’s sending out light rays in every direction. We’re here in Earth and catch only the rays emitted in our direction. But suppose there’s a black hole exactly in the way of the direct beam.”

“We couldn’t see the star, I get that.”

“Well, actually we could see some of its light, thanks to the massive black hole’s ray-bending trick. Rays that would have missed us are bent inward towards our telescope. The net effect is similar to having a big magnifying lens out there, focusing the star’s light on us.”

“You said, ‘similar.’ How’s it different?”

“In the pattern of light deflection. Your standard Sherlock magnifying lens bends light most strongly at the edges so all the light is directed towards a point. Gravitational lenses bend light most strongly near the center. Their light pattern is hollow. If we’re exactly in a straight line with the star and the black hole, we see the image ‘focused’ to a ring.”

“That’d be the Einstein ring, right?”

“Yes, he gets credit because he was the one who first set out the equation for how the rays would converge. We don’t see the star, but we do see the ring. His equation says that the angular size of the ring grows as the square root of the deflecting object’s mass. That’s the basis of a widely-used technique for measuring the masses not only of black holes but of galaxies and even larger structures.”

“The magnification makes the star look brighter?”

“Brighter only in the sense that we’re gathering photons from a wider field then if we had only the direct beam. The lens doesn’t make additional photons, probably.”

Suddenly I’m interested. “Probably?”

“Yes, Sy, theoreticians have suggested a couple of possible effects, but to my knowledge there’s no good evidence yet for either of them. You both know about Hawking radiation?”

“Sure.”

“Yup.”

“Well, there’s the possibility that starlight falling on a black hole’s event horizon could enhance virtual particle production. That would generate more photons than one would expect from first principles. On the other hand, we don’t really have a good handle on first principles for black holes.”

“And the other effect?”

“There’s a stack of IFs under this one. IF dark matter exists and if the lens is a concentration of dark matter, then maybe photons passing through dark matter might have some subtle interaction with it that could generate more photons. Like I said, no evidence.”

“Hundreds, you say.”

“Pardon?”

“We’ve found hundreds of these lenses.”

“All it takes is for one object to be more-or-less behind some other object that’s heavy enough to bend light towards us.”

“Seein’ the forest by using the trees, I guess.”

“That’s a good way to put, it, Vinnie.”

~~ Rich Olcott

The thing about Al’s coffee shop is that there’s generally a good discussion going on, usually about current doings in physics or astronomy. This time it’s in the physicist’s corner but they’re not writing equations on the whiteboard Al put up over there to save on paper napkins. I step over there and grab an empty chair.

The thing about Al’s coffee shop is that there’s generally a good discussion going on, usually about current doings in physics or astronomy. This time it’s in the physicist’s corner but they’re not writing equations on the whiteboard Al put up over there to save on paper napkins. I step over there and grab an empty chair.

Jennie’s turn — “Didn’t the chemists define away a whole lot of entropy when they said that pure elements have zero entropy at absolute zero temperature?”

Jennie’s turn — “Didn’t the chemists define away a whole lot of entropy when they said that pure elements have zero entropy at absolute zero temperature?”

“That’s not quite what I said, Jennie. Old Reliable’s software and and I worked up a hollow-shell model and to my surprise it’s consistent with one of Stephen Hawking’s results. That’s a long way from saying that’s what a black hole is.”

“That’s not quite what I said, Jennie. Old Reliable’s software and and I worked up a hollow-shell model and to my surprise it’s consistent with one of Stephen Hawking’s results. That’s a long way from saying that’s what a black hole is.” My notes say D is the black hole’s diameter and d is another object’s distance from its center. One second in the falling object’s frame would look like f seconds to us. But one mile would look like 1/f miles. The event horizon is where d equals the half-diameter and f goes infinite. The formula only works where the object stays outside the horizon.”

My notes say D is the black hole’s diameter and d is another object’s distance from its center. One second in the falling object’s frame would look like f seconds to us. But one mile would look like 1/f miles. The event horizon is where d equals the half-diameter and f goes infinite. The formula only works where the object stays outside the horizon.” “Wow, Old Reliable looks up stuff and takes care of unit conversions automatically?”

“Wow, Old Reliable looks up stuff and takes care of unit conversions automatically?”

“Wait, Mr Moire, we said that the event horizon’s just a mathematical construct,

“Wait, Mr Moire, we said that the event horizon’s just a mathematical construct,