<chirp, chirp> “Moire here.”

“Hi, Sy. Vinnie. Hey, I’ve been reading through some of your old stuff—”

“That bored, eh?”

“You know it. Anyhow, something just don’t jibe, ya know?”

“I’m not surprised but I don’t know. Tell me about it.”

“OK, let’s start with your Einstein’s Bubble piece. You got this electron goes up‑and‑down in some other galaxy and sends out a photon and it hits my eye and an atom in there absorbs it and I see the speck of light, right?”

“That’s about the size of it. What’s the problem?”

“I ain’t done yet. OK, the photon can’t give away any energy on the way here ’cause it’s quantum and quantum energy comes in packages. And when it hits my eye I get the whole package, right?”

“Yes, and?”

“And so there’s no energy loss and that means 100% efficient and I thought thermodynamics says you can’t do that.”

“Ah, good point. You’ve just described one version of Loschmidt’s Paradox. A lot of ink has gone into the conflict between quantum mechanics and relativity theory, but Herr Johann Loschmidt found a fundamental conflict between Newtonian mechanics, which is fundamental, and thermodynamics, which is also fundamental. He wasn’t talking photons, of course — it’d be another quarter-century before Planck and Einstein came up with that notion — but his challenge stood on your central issue.”

“Goody for me, so what’s the central issue?”

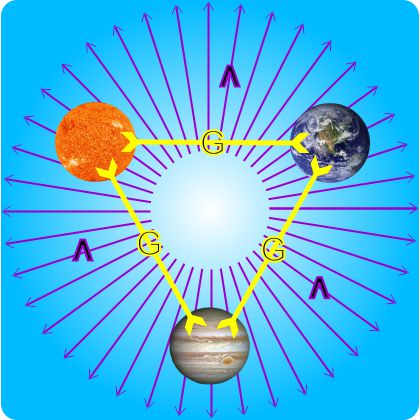

“Whether or not things can run in reverse. A pendulum that swings from A to B also swings from B to A. Planets go around our Sun counterclockwise, but Newton’s math would be just as accurate if they went clockwise. In all his equations and everything derived from them, you can replace +t with ‑t to make run time backwards and everything looks dandy. That even carries over to quantum mechanics — an excited atom relaxes by emitting a photon that eventually excites another atom, but then the second atom can play the same game by tossing a photon back the other way. That works because photons don’t dissipate their energy.”

“I get your point, Newton-style physics likes things that can back up. So what’s Loschmidt’s beef?”

“Ever see a fire unburn? Down at the microscopic level where atoms and photons live, processes run backwards all the time. Melting and freezing and chemical equilibria depend upon that. Things are different up at the macroscopic level, though — once heat energy gets out or randomness creeps in, processes can’t undo by themselves as Newton would like. That’s why Loschmidt stood the Laws of Thermodynamics up against Newton’s Laws. The paradox isn’t Newton’s fault — the very idea of energy was just being invented in his time and of course atoms and molecules and randomness were still centuries away.”

“Micro, macro, who cares about the difference?”

“The difference is that the micro level is usually a lot simpler than the macro level. We can often use measured or calculated micro‑level properties to predict macro‑level properties. Boltzmann started a whole branch of Physics, Statistical Mechanics, devoted to carrying out that strategy. For instance, if we know enough about what happens when two gas molecules collide we can predict the speed of sound through the gas. Our solid‑state devices depend on macro‑level electric and optical phenomena that depend on micro‑level electron‑atom interactions.”

“Statistical?”

“As in, ‘we don’t know exactly how it’ll go but we can figure the odds…‘ Suppose we’re looking at air molecules and the micro process is a molecule moving. It could go left, right, up, down, towards or away from you like the six sides of a die. Once it’s gone left, what are the odds it’ll reverse course?”

“About 16%, like rolling a die to get a one.”

“You know your odds. Now roll that die again. What’s the odds of snake‑eyes?”

“16% of 16%, that’s like 3 outa 100.”

“There’s a kajillion molecules in the room. Roll the die a kajillion times. What are the odds all the air goes to one wall?”

“So close to zero it ain’t gonna happen.”

“And Boltzmann’s Statistical Mechanics explained why not.”

“Knowing about one molecule predicts a kajillion. Pretty good.”

Photo by Rich Niewiroski Jr. / CC BY 2.5

~~ Rich Olcott