“Anne?”

“Mm?”

“Remember when you said that other reality, the one without the letter ‘C,’ felt more probable than this one?”

“Mm-mm.”

“What tipped you off?”

“Now you’re asking?”

“I’m a physicist, physicists think about stuff. Besides, we’ve finished the pizza.”

<sigh> “This conversation has gotten pretty improbable, if you ask me. Oh, well. Umm, I guess it’s two things. The more-probable realities feel denser somehow, and more jangly. What got you on this track?”

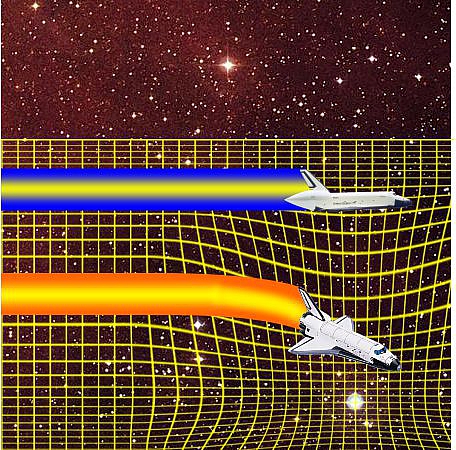

“Conservation of energy. Einstein’s E=mc² says your mass embodies a considerable amount of energy, but when you jump out of this reality there’s no flash of light or heat, just that fizzing sound. When you come back, no sudden chill or things falling down on us, just the same fizzing. Your mass-energy that has to go to or come from somewhere. I can’t think where or how.”

“I certainly don’t know, I just do it. Do you have any physicist guesses?”

“Questions first.”

“If you must.”

“It’s what I do. What do you perceive during a jump? Maybe something like falling, or heat or cold?”

“There’s not much ‘during.’ It’s not like I go through a tunnel, it’s more like just turning around. What I see goes out of focus briefly. Mostly it’s the fizzy sound and I itch.”

“Itch. Hmm… The same itch every jump?”

“That’s interesting. No, it’s not. I itch more if I jump to a more-probable reality.”

“Very interesting. I’ll bet you don’t get that itch if you’re doing a pure time-hop.”

“You’re right! OK, you’re onto something, give.”

“You’ve met one of my pet elephants.”

“Wha….??”

“A deep question that physics has been nibbling around for almost two centuries. Like the seven blind men and the elephant. Except the physicists aren’t blind and the elephant’s pretty abstract. Ready for a story?”

“Pour me another and I will be.”

“Here you go. OK, it goes back to steam engines. People were interested in getting as much work as possible out of each lump of coal they burned. It took a couple of decades to develop good quantitative concepts of energy and work so they could grade coal in terms of energy per unit weight, but they got there. Once they could quantify energy, they discovered that each material they measured — wood, metals, water, gases — had a consistent heat capacity. It always took the same amount of energy to raise its temperature across a given range. For a kilogram of water at 25°C, for instance, it takes one kilocalorie to raise its temperature to 26°C. Lead and air take less.”

“So where’s the elephant come in?”

“I’m getting there. We started out talking about steam engines, remember? They work by letting steam under pressure push a piston through a cylinder. While that’s happening, the steam cools down before it’s puffed out as that classic old-time Puffing Billy ‘CHUFF.’ Early engine designers thought the energy pushing the piston just came from trading off pressure for volume. But a guy named Carnot essentially invented thermodynamics when he pointed out that the cooling-down was also important. The temperature drop meant that heat energy stored in the steam must be contributing to the piston’s motion because there was no place else for it to go.”

“I want to hear about the elephant.”

“Almost there. The question was, how to calculate the heat energy.”

“Why not just multiply the temperature change by the heat capacity?”

“That’d work if the heat capacity were temperature-independent, which it isn’t. What we do is sum up the capacity at each intervening temperature. Call the sum ‘elephant’ though it’s better known as Entropy. Pressure, Volume, Temperature and Entropy define the state of a gas. Using those state functions all you need to know is the working fluid’s initial and final state and you can calculate your engine. Engineers and chemists do process design and experimental analysis using tables of reported state function values for different substances at different temperatures.”

“Do they know why heat capacity changes?”

“That took a long time to work out, which is part of why entropy’s an elephant. And you’ve just encountered the elephant’s trunk.”

“There’s more elephant?”

“And more of this. Want a refill?”

~~ Rich Olcott

“A few. The most important for this discussion is energy and time.”

“A few. The most important for this discussion is energy and time.”

“OK,

“OK,