<transcript of smartphone dictation by Sy Moire, hard‑boiled physicist>

Day 173 of self‑isolation….

Perfect weather for a brisk solitary walk, taking the park route….

There’s the geese. No sign of Mr Feder, just as well….

Still thinking about Ms Baird and her plan for generating electric power from a black hole named Lonesome….

Can just hear Vinnie if I ever told him about this which I can’t….

“Hey, Sy, nothin’ gets out of a black hole except gravity, but she’s using Lonesome‘s magnetic field to generate electricity which is electromagnetic. How’s that happen?”

Good question….

Hhmph, that’s one angry squirrel….

Ah, a couple of crows pecking the ground under its tree. Maybe they’re too close to its acorn stash….

We know a black hole’s only measurable properties are its mass, charge and spin….

And maybe its temperature, thanks to Stephen Hawking….

Its charge is static — hah! cute pun — wouldn’t support continuous electrical generation….

The Event Horizon hides everything inside — we can’t tell if charge moves around in there or even if it’s matter or anti‑matter or something else….

The no‑hair theorem says there’s no landmarks or anything sticking out of the Event Horizon so how do we know the thing’s even spinning?

Ah, we know a black hole’s external structures — the jets, the Ergosphere belt and the accretion disk — rotate because we see red- and blue-shifted radiation from them….

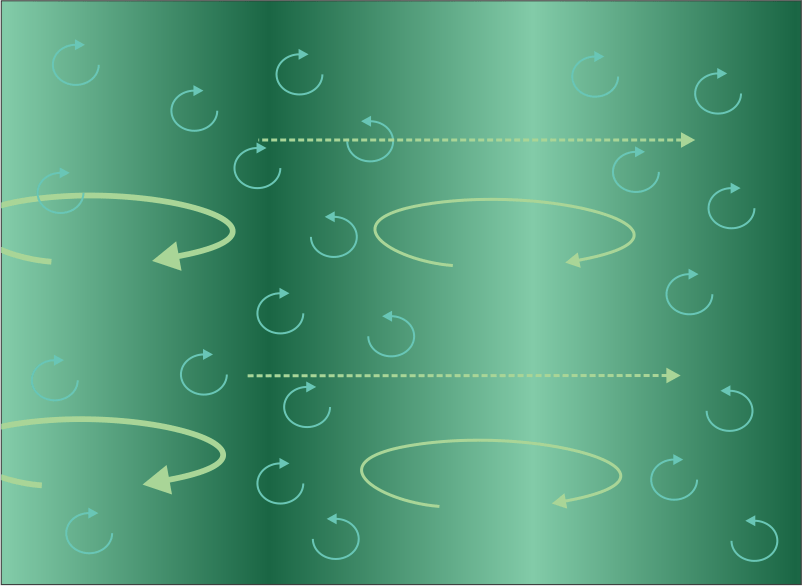

The Ergosphere rotates in lockstep with Lonesome‘s contents because of gravitational frame-dragging….

Probably the disk and the jets do, too, but that’s only a strong maybe….

But why should the Ergosphere’s rotation generate a magnetic field?

How about Newt Barnes’ double‑wheel idea — a belt of charged light‑weight particles inside a belt of opposite‑charged heavy particles all embedded in the Ergosphere and orbiting at the black hole’s spin rate….

Could such a thing exist? Can simple particle collisions really split the charges apart like that?….

OK, fun problem for strolling mental arithmetic. Astronomical “dust” particles are about the size of smoke particles and those are about a micrometer across which is 10‑6 meter so the volume’s about (10‑6)3=10‑18 cubic meter and the density’s sorta close to water at 1 gram per cubic centimeter or a thousand kilograms per cubic meter so the particle mass is about 10‑18×103=10‑15 kilogram. If a that‑size particle collided with something and released just enough kinetic energy to knock off an electron, how fast was it going?

Ionization energy for a hydrogen atom is 13 electronvolts, so let’s go for a collision energy of at least 10 eV. Good old kinetic energy formula is E=½mv² but that’s got to be in joules if we want a speed in meters per second so 10 eV is, lemme think, about 2×10‑18 joules/particle. So v² is 2×2×10‑18/10‑15 which is 4×10‑3 or 40×10‑4, square root of 40 is about 6, so v is about 6×10‑2 or 0.06 meters per second. How’s that compare with typical speeds near Lonesome?

Ms Baird said that Lonesome‘s mass is 1.5 Solar masses and it’s isolated from external gravity and electromagnetic fields. So anything near it is in orbit and we can use the circular orbit formula v²=GM/r….

Dang, don’t remember values for G or M. Have to cheat and look up the Sun’s GM product on Old Reliable….

Ah-hah, 1.3×1020 meters³/second so Lonesome‘s is also near 1020….

A solar‑mass black hole’s half‑diameter is about 3 kilometers so Lonesome‘s would be about 5×103 meters. Say we’re orbiting at twice that so r‘s around 104 meters. Put it together we get v2=1020/104=1016 so v=108 meters/sec….

Everything’s going a billion times faster than 10 eV….

So yeah, no problem getting charged dust particles out there next to Lonesome….

Just look at the color in that tree…

Weird when you think about it. The really good color is summertime chlorophyll green when the trees are soaking up sunlight and turning CO2 into oxygen for us but people get excited about dying leaves that are red or yellow…

Well, now. Lonesome‘s Event Horizon is the no-going-back point on the way to its central singularity which we call infinity because its physics are beyond anything we know. I’ve just closed out another decade of my life, another Event Horizon on my own one‑way path to a singularity…

Hey! Mr Feder! Come ask me a question to get me out of this mood.

Author’s note — Yes, ambient radiation in Lonesome‘s immediate vicinity probably would account for far more ionization than physical impact, but this was a nice exercise in estimation and playing with exponents and applied physical principles.

~~ Rich Olcott