<chirp, chirp> “Moire here.”

“Hiya, Sy, it’s me again.”

“Hi, Eddie. I thought you were done with your deliveries tonight. That was a good stromboli, by the way, just the right amount of zing and sauce.”

“Thanks. Yeah, I’m done for the day, but I was thinking while I drove home. We said that the Feds and the banks together can tinker with the money supply so there’s no Conservation of Money like we got Conservation of Energy. But then we said that it matters to keep money in local businesses instead of letting it drain away somewhere else. That says there’s only so much to go around like the amount doesn’t change. So which is it?”

“Good point. You’ve touched on another contrasting parallel between Physics and Economics. In Physics we mostly understand how atoms work and we’ve got a pretty good handle on the forces that control objects big enough to see. J Willard Gibbs, probably the foremost physicist of the late 1800s, devised Statistical Mechanics to bridge the gap between the two levels. The idea is to start with the atoms or molecules. They’re quantum objects, of course, so we can’t have much precise information at that level. What we can get, though, is averages and spreads on one object’s properties — speed, internal energy levels, things like that. Imagine we have an ensemble of those guys, mostly identical but each with their own personal set of properties. Gibbs showed us how to apply low-level averages and spreads across the whole ensemble to calculate upper-level properties like magnetic strength and heat capacity.”

“Ensemble. Fancy word.”

“Not my word, blame Gibbs. He invented the field so we go with his terminology. Atoms weren’t quite a respectable topic of conversation at the time so he kept things general and talked about ‘macroscopic properties‘ which we can measure directly and ‘microscopic properties‘ which were mysterious at the time. Think of three flasks holding samples of some kind of gas, OK?”

“No problem.”

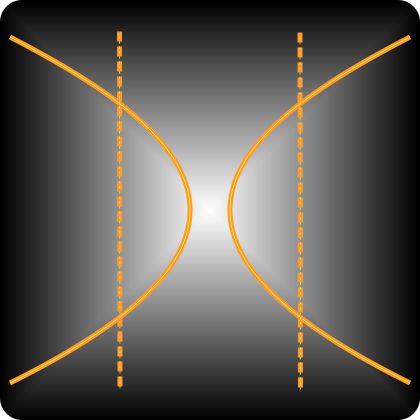

“The first flask is stoppered, no gas can get in or out but energy can pass through the flask’s wall. Gibbs would call the confined collection of molecules a ‘canonical ensemble‘. Because the wall transmits energy we can use an external thermometer to measure the ensemble’s temperature. Other than that, all we know about the contents is the number of particles and the volume the particles can access.”

“Canonical?”

“In Gibbs’ usage it means that he’s pared things down to an abstract essence. It doesn’t matter whether what’s inside is atoms or fruitflies, his logic still holds. Now for flask number two. It’s heavily insulated so whatever energy it had inside originally, that’s what it’s got now. We can’t measure the temperature in this one. Gibbs would consider the particles in there to be a ‘microcanonical ensemble,’ with the ‘micro’ indicating the energy restriction.”

“Where there’s a microcanonical there’s gotta be a macrocanonical.”

“You’d think, but Gibbs used the term ‘grand canonical ensemble‘ instead. That’s flask number three, which has neither insulation nor stopper. Both energy and matter are free to enter or leave the ensemble. Gibbs’ notion of canonical ensembles and the math that grows out of them have been used in every kind of analysis from solid state physics to cybersecurity.”

“OK, I think I see where you’re going here. Money acts sorta like energy so you’re gonna lay out three kinds of economy restriction.”

“You’re way ahead of me and the economists, Eddie. They’ve only got two levels, though they do use reasonable names for them — microeconomics and macroeconomics. For them the micro level is about individuals, businesses, the markets they play in and how they spend their incomes. Supply-demand thinking gets used a lot.”

“That figures. What about macro?”

“Macro level is about regions and countries and the world. Supply‑demand plays here, too, except the macroeconomists worry about how demand for money itself affects its value compared to everything else.”

“They got bridges like Gibbs built?”

“Nope. Atoms are simple, people are complicated. The economists are still arguing about the basics. Anyway, the economists’ micro level assumes local money stays local and has a stable value.”

“Keeping my business stable is good.”

~~ Rich Olcott