Eddie’s diner serves tasty pizza, but his music playlist’s tasty, too — heavy with small-group vocals. We’re talking atomic structure but suddenly Vinnie surprises me. “Whoa, she’s got a hot voice!”

“Who?”

“That girl who’s singing.”

“Which one? That’s a quartet.”

“The alto.”

“How can you pick one voice out of that close-harmony performance?”

“By listening! She’s the only one singing those notes.”

“You’re hearing a chaotic sound wave yet you can pick out just one sound.”

“Yeah, just her special notes.”

“Interesting thing is, atoms do that, too. Think about, say, a uranium atom, 92 electrons attracted by the nucleus, repelled by every other electron, all dashing about in the nuclear field and getting in each other’s way. Think that’d be a nice, orderly picture?”

“Sure not. It’d be, like you say, chaotic.”

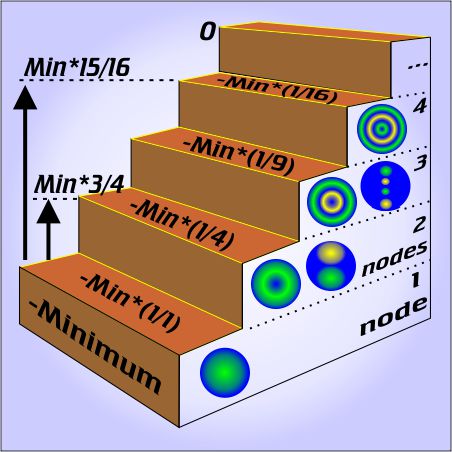

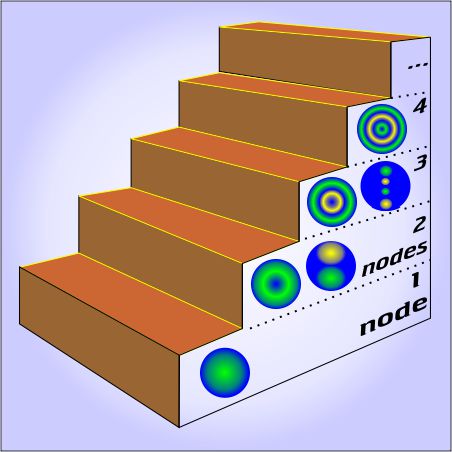

“But just like we can describe a messy sound wave as a combination of frequencies, we can describe that atom’s electron structure as a combination of basic patterns.” I pull Old Reliable from its holster and bring up an image. “Here’s something I built for a presentation. It’s a little busy so I’ll walk you through it.”

“Busy, uh-huh.”

“Start with those blue circles. They look familiar?”

“Right, they’re Laplace’s spherical patterns. You got them sorted by how many blue spaces they got.”

“Yup. Blue represents a node, a 2-D region where the value touches or crosses zero. There are patterns with three or more nodes, but I ran out of space and patience to draw them. Laplace showed there’s an infinite number of candidate patterns as you add more and more nodes. You can describe any physically reasonable distribution around the central point as some combination of his patterns.”

“Why’d you draw them on stair-steps?”

“Because each step (we call it a shell) is at a different potential energy level. Suppose, for instance, that there’s charge in that one-node pattern. Moving it away from the nucleus puts a node there. That’ll cost some energy and shift charge to the two-node shell. To exclude it from there and also from another node, say a larger spherical surface, would take even more energy, and so on.”

“How is that potential energy?”

“We’re comparing shell energy to the energy of an electron that’s far away. It’s like gravitational potential energy, maybe the energy a space rock converts to kinetic energy as it falls to Earth. Call the far-away energy zero. The numbers get more and more negative as the rock or the charge get closer to the center of attraction.”

“Ah, so that’s why you’ve got minus signs in the picture.”

“Exactly. See zero at the top of the stairs? With a hydrogen atom, for instance, an electron would give up 13.6 electron-volts of energy to get close to the nucleus in that 1-node pattern. Conversely, it’d take 13.6 eV to rip that charge completely away.”

“If the 13.6 is what you’re calling ‘Minimum’, why not just write ‘–13.6’ in there?”

“It’s a different number for different atoms and even ions. Astronomers see all kinds of ions with every amount of charge so they have to keep things general in their calculations.”

“What are those fractions about? Wait, don’t tell me, I can figure this. Each divisor is the square of its node count. Are those the 1/n² numbers from whosit’s formula?”

“Rydberg’s. You’re on the right track, keep going.”

“If the minimum is 13.6 eV, the diagram says that the two-node shell is … 3.4 eV down from the top and … 10.2 eV up from the bottom. And from what we said about the hydrogen spectrum, I’ll bet that 10.2 eV jump is the first line in that, was it the Ly series, the one in the ultra-violet?”

“Bravo, Vinnie! The Lyman series it is. Excellent memory for detail there.”

“I noticed something else. You carefully didn’t say we moved an electron between shells.”

“That’s an important point. At the atomic size scale we can’t treat the electron as a particle moving around. Lightwaves act to turn off one shell and excite another one, like your singer exciting a different note.”

“Yes, she does.”

~~ Rich Olcott

- Thanks to the Molnars for a delightful meal, and to their dinner party guests the Jumps for instigating this post.

“Wait, Mr Moire, we said that the event horizon’s just a mathematical construct,

“Wait, Mr Moire, we said that the event horizon’s just a mathematical construct,

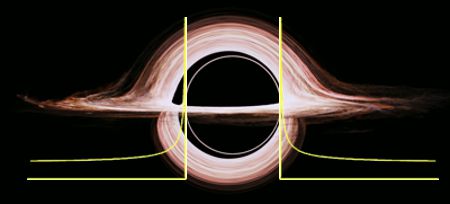

, where D is the object’s diameter and d is your distance from it. Suppose the Sun suddenly collapsed without losing any mass to become a Schwarzchild object. The object’s diameter would be a bit less than 4 miles. Earth is 93 million miles from the Sun so the compression factor here would be [poking numbers into my smartphone] 1.000_000_04. Nothing you’d notice. It’d be 1.000_000_10 at Mercury. You wouldn’t see even 1% compression until you got as close as 378 miles, 10% only inside of 43 miles. Fifty percent of the effect shows up in the last 13 miles. The edge of a black hole is sharper than this pizza knife.”

, where D is the object’s diameter and d is your distance from it. Suppose the Sun suddenly collapsed without losing any mass to become a Schwarzchild object. The object’s diameter would be a bit less than 4 miles. Earth is 93 million miles from the Sun so the compression factor here would be [poking numbers into my smartphone] 1.000_000_04. Nothing you’d notice. It’d be 1.000_000_10 at Mercury. You wouldn’t see even 1% compression until you got as close as 378 miles, 10% only inside of 43 miles. Fifty percent of the effect shows up in the last 13 miles. The edge of a black hole is sharper than this pizza knife.”

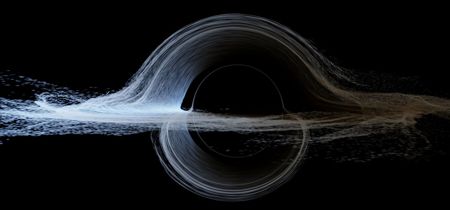

. A is proportional to spin. When A is small (not much spin) or the distance is large those A/d² terms essentially vanish relative to the others and the scaling looks just like the simple almost-a-point Schwarzchild case. When A is large or the distance is small the A/d² terms dominate top and bottom, the factor equals 1 and there’s dragging but no compression. In the middle, things get interesting and that’s where Dr Thorne played.”

. A is proportional to spin. When A is small (not much spin) or the distance is large those A/d² terms essentially vanish relative to the others and the scaling looks just like the simple almost-a-point Schwarzchild case. When A is large or the distance is small the A/d² terms dominate top and bottom, the factor equals 1 and there’s dragging but no compression. In the middle, things get interesting and that’s where Dr Thorne played.”