“Wait, Sy, you’ve made this explanation way more complicated than it has to be. All I asked about was the horrible whirling I’d gotten myself into. The three angular coordinates part would have done for that, but you dragged in degrees of freedom and deep symmetry and even dropped in that bit about ‘if measurable motion is defined.’ Why bother with all that and how can you have unmeasurable motion?”

“Curiosity caught the cat, didn’t it? Let’s head down to Eddie’s and I’ll treat you to a gelato. Your usual scoop of mint, of course, but I recommend combining it with a scoop of ginger to ease your queasy.”

“You’re a hard man to turn down, Sy. Lead on.”

<walking the hall to the elevators> “Have you ever baked a cake, Anne?”

“Hasn’t everyone? My specialty is Crazy Cake — flour, sugar, oil, vinegar, baking soda and a few other things but no eggs.”

“Sounds interesting. Well, consider the path from fixings to cake. You’ve collected the ingredients. Is it a cake yet?”

“Of course not.”

“Ok, you’ve stirred everything together and poured the batter into the pan. Is it a cake yet?”

“Actually, you sift the dry ingredients into the pan, then add the others separately, but I get your point. No, it’s not cake and it won’t be until it’s baked and I’ve topped it with my secret frosting. Some day, Sy, I’ll bake you one.”

<riding the elevator down to 2> “You’re a hard woman to turn down, Anne. I look forward to it. Anyhow, you see the essential difference between flour’s journey to cakehood and our elevator ride down to Eddie’s.”

“Mmm… OK, it’s the discrete versus continuous thing, isn’t it?”

“You’ve got it. Measuring progress along a discrete degree of freedom can be an iffy proposition.”

“How about just going with the recipe’s step number?”

“I’ll bet you use a spoon instead of a cup to get the right amount of baking soda. Is that a separate step from cup‑measuring the other dry ingredients? Sifting one batch or two? Those’d change the step‑number metric and the step-by-step equivalent of momentum. It’s not a trivial question, because Emmy Noether’s symmetry theorem applies only to continuous coordinates.”

“We’re back to her again? I thought—”

The elevator doors open at the second floor. We walk across to Eddie’s, where the tail‑end of the lunch crowd is dawdling over their pizzas. “Hiya folks. You’re a little late, I already shut my oven down.”

“Hi, Eddie, we’re just here for gelato. What’s your pleasure, Anne?”

“On Sy’s recommendation, Eddie, I’ll try a scoop of ginger along with my scoop of mint. Sy, about that symmetry theorem—”

“The same for me, Eddie.”

“Comin’ up. Just find a table, I’ll bring ’em over.”

We do that and he does that. “Here you go, folks, two gelati both the same, all symmetrical.”

“Eddie, you’ve been eavesdropping again!”

“Who, me? Never! Unless it’s somethin’ interesting. So symmetry ain’t just pretty like snowflakes? It’s got theorems?”

“Absolutely, Eddie. In many ways symmetry appears to be fundamental to how the Universe works. Or we think so, anyway. Here, Anne, have an extra bite of my ginger gelato. For one thing, Eddie, symmetry makes calculations a lot easier. If you know a particular system has the symmetry of a square, for instance, then you can get away with calculating only an eighth of it.”

“You mean a quarter, right, you turn a square four ways.”

“No, eight. It’s done with mirrors. Sy showed me.”

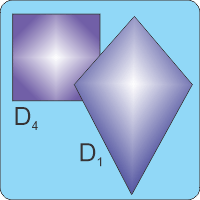

“I’m sure he did, Anne. But Sy, what if it’s not a perfect square? How about if one corner’s pulled out to a kite shape?”

“That’s called a broken symmetry, no surprise. Physicists and engineers handle systems like that with a toolkit of approximations that the mathematicians don’t like. Basically, the idea is to start with some nice neat symmetrical solution then add adjustments, called perturbations, to tweak the solution to something closer to reality. If the kite shape’s not too far away from squareness the adjusted solution can give you some insight onto how the actual thing works.”

“How about if it’s too far?”

“You go looking for a kite‑shaped solution.”

~~ Rich Olcott

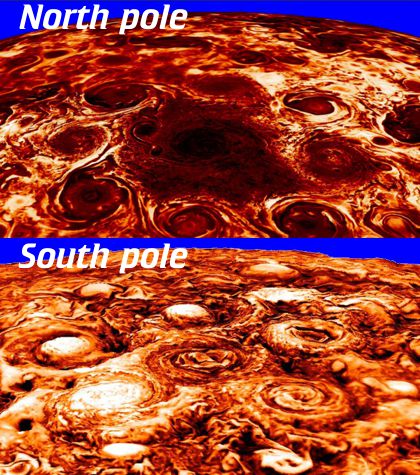

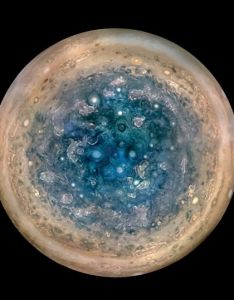

“They’re certainly eye-catching, but I thought Jupiter’s all baby-blue and salmon-colored.”

“They’re certainly eye-catching, but I thought Jupiter’s all baby-blue and salmon-colored.”

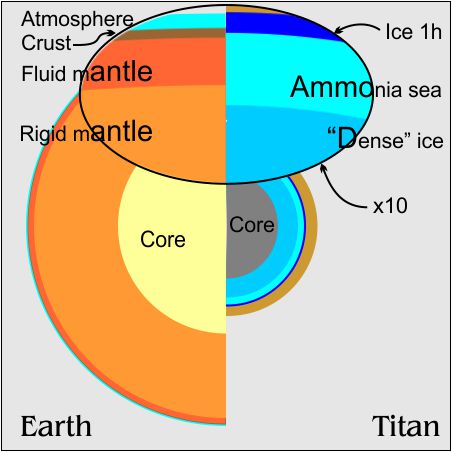

The primary reason we think Titan is so wet is that Titan’s density is about halfway between rock and water. We know there are other light molecules on Titan — ammonia, methane, etc. We don’t know how much of each. Those compounds don’t have water’s complex phase behavior but many can dissolve in it. That’s why that hypothetical “Ammonia sea” is in the top diagram.

The primary reason we think Titan is so wet is that Titan’s density is about halfway between rock and water. We know there are other light molecules on Titan — ammonia, methane, etc. We don’t know how much of each. Those compounds don’t have water’s complex phase behavior but many can dissolve in it. That’s why that hypothetical “Ammonia sea” is in the top diagram.