The Crazy Theory contest is still going strong in the back room at Al’s coffee shop. I gather from the score board scribbles that Jim’s Mars idea (one mark-up says “2 possible 2 B crazy!“) is way behind Amanda’s “green blood” theory. There’s some milling about, then a guy next to me says, “I got this, hold my coffee,” and steps up to the mic. Big fellow, don’t recognize him but some of the Physics students do — “Hey, it’s Cap’n Mike at the mic. Whatcha got for us this time?”

“I got the absence of a theory, how’s that? It’s about the Four Forces.”

Someone in the crowd yells out, “Charm, Persuasiveness, Chaos and Bloody-mindedness.”

“Nah, Jennie, that’s Terry Pratchett’s Theory of Historical Narrative. We’re doing Physics here. The right answer is Weak and Strong Nuclear Forces, Electromagnetism, and Gravity, with me? Question is, how do they compare?”

Another voice from the crowd. “Depends on distance!”

“Well yeah, but let’s look at cases. Weak Nuclear Force first. It works on the quarks that form massive particles like protons. It’s a really short-range force because it depends on force-carrier particles that have very short lifetimes. If a Weak Force carrier leaves its home particle even at the speed of light which they’re way too heavy to do, it can only fly a small fraction of a proton radius before it expires without affecting anything. So, ineffective anywhere outside a massive particle.”

It’s a raucous crowd. “How about the Strong Force, Mike?”

. <chorus of “HOO-wah!”>

“Semper fi that. OK, the carriers of the Strong Force —”

. <“Naa-VY! Naaa-VY!”>

. <“Hush up, guys, let him finish.”>

“Thanks, Amanda. The Strong Force carriers have no mass so they fly at lightspeed, but the force itself is short range, falls off rapidly beyond the nuclear radius. It keeps each trio of quarks inside their own proton or neutron. And it’s powerful enough to corral positively-charged particles within the nucleus. That means it’s way stronger inside the nucleus than the Electromagnetic force that pushes positive charges away from each other.”

“How about outside the nucleus?”

“Out there it’s much weaker than Electromagnetism’s photons that go flying about —”

. <“Air Force!”>

. <“You guys!”>

“As I was saying… OK, the Electromagnetic Force is like the nuclear forces because it’s carried by particles and quantum mechanics applies. But it’s different from the nuclear forces because of its inverse-square distance dependence. Its range is infinite if you’re willing to wait a while to sense it because light has finite speed. The really different force is the fourth one, Gravity —”

. <“Yo Army! Ground-pounders rock!”>

“I was expecting that. In some ways Gravity’s like Electromagnetism. It travels at the same speed and has the same inverse-square distance law. But at any given distance, Gravity’s a factor of 1038 punier and we’ve never been able to detect a force-carrier for it. Worse, a century of math work hasn’t been able to forge an acceptable connection between the really good Relativity theory we have for Gravity and the really good Standard Model we have for the other three forces. So here’s my Crazy Theory Number One — maybe there is no connection.”

. <sudden dead silence>

“All the theory work I’ve seen — string theory, whatever — assumes that Gravity is somehow subject to quantum-based laws of some sort and our challenge is to tie Gravity’s quanta to the rules that govern the Standard Model. That’s the way we’d like the Universe to work, but is there any firm evidence that Gravity actually is quantized?”

. <more silence>

“Right. So now for my Even Crazier Theories. Maybe there’s a Fifth Force, also non-quantized, even weaker than Gravity, and not bound by the speed of light. Something like that could explain entanglement and solve Einstein’s Bubble problem.”

. <even more silence>

“OK, I’ll get crazier. Many of us have had what I’ll call spooky experiences that known Physics can’t explain. Maybe stupid-good gambling luck or ‘just knowing’ when someone died, stuff like that. Maybe we’re using the Fifth Force in action.”

. <complete pandemonium>

~ Rich Olcott

Note to my readers with connections to the US National Guard, Coast Guard, Merchant Marine and/or Public Health Service — Yeah, I know, but one can only stretch a metaphor so far.

With my finger I draw in the frost on his gelato cabinet. “Imagine this is a brass ball, except I’ve pulled one side of it out to a cone. Someone’s loaded it up with extra electrons so it’s carrying a high negative charge.”

With my finger I draw in the frost on his gelato cabinet. “Imagine this is a brass ball, except I’ve pulled one side of it out to a cone. Someone’s loaded it up with extra electrons so it’s carrying a high negative charge.”

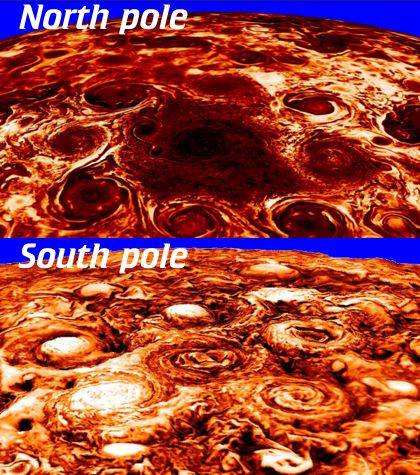

“They’re certainly eye-catching, but I thought Jupiter’s all baby-blue and salmon-colored.”

“They’re certainly eye-catching, but I thought Jupiter’s all baby-blue and salmon-colored.”

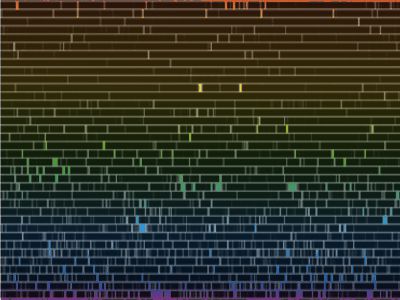

“So you’re telling me, Cathleen, that you can tell how hot a star is by

“So you’re telling me, Cathleen, that you can tell how hot a star is by  Cathleen turns to her laptop and starts tapping keys. “Let’s do an example. Suppose we’re looking at a star’s broadband spectrogram. The blackbody curve peaks at 720 picometers. There’s an absorption doublet with just the right relative intensity profile in the near infra-red at 1,060,190 and 1,061,265 picometers. They’re 1,075 picometers apart. In the lab, the sodium doublet’s split by 597 picometers. If the star’s absorption peaks are indeed the sodium doublet then the spectrum has been stretched by a factor of 1075/597=1.80. Working backward, in the star’s frame its blackbody peak must be at 720/1.80=400 picometers, which corresponds to a temperature of about 6,500 K.”

Cathleen turns to her laptop and starts tapping keys. “Let’s do an example. Suppose we’re looking at a star’s broadband spectrogram. The blackbody curve peaks at 720 picometers. There’s an absorption doublet with just the right relative intensity profile in the near infra-red at 1,060,190 and 1,061,265 picometers. They’re 1,075 picometers apart. In the lab, the sodium doublet’s split by 597 picometers. If the star’s absorption peaks are indeed the sodium doublet then the spectrum has been stretched by a factor of 1075/597=1.80. Working backward, in the star’s frame its blackbody peak must be at 720/1.80=400 picometers, which corresponds to a temperature of about 6,500 K.”

“You’re right, Sy. It’s not a particularly pretty picture, but it shows that nice strong sodium doublet in the yellow and the broad iron and hydrogen lines down in the green and blue. I’ll admit it, Vinnie, this is a faked image I made to show my students what the solar atmosphere would look like if you could turn off the photosphere’s continuous blast of light. The point is that the atoms emit exactly the same sets of colors that they absorb.”

“You’re right, Sy. It’s not a particularly pretty picture, but it shows that nice strong sodium doublet in the yellow and the broad iron and hydrogen lines down in the green and blue. I’ll admit it, Vinnie, this is a faked image I made to show my students what the solar atmosphere would look like if you could turn off the photosphere’s continuous blast of light. The point is that the atoms emit exactly the same sets of colors that they absorb.”

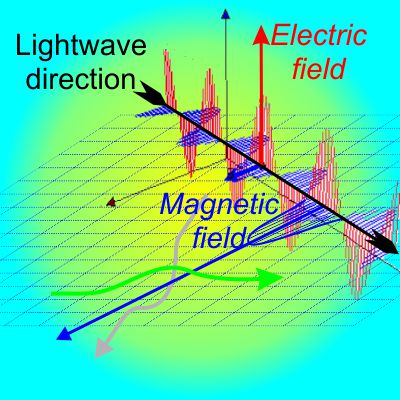

“It told me that the magnetism stuff has to come from what electrons do. And that’s when I came up with this drawing.” <He shoves a paper napkin at me.> “See, the three balls are electrons and they’re all negative-negative pushing against each other only I’m just paying attention to what the red one’s doing to the other two. Got that?”

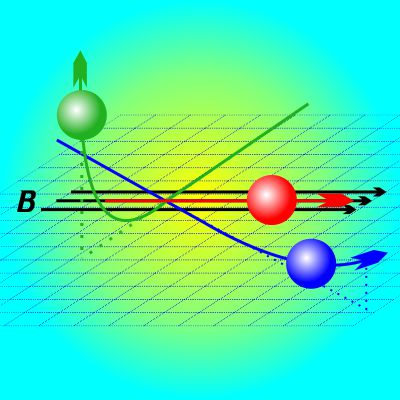

“It told me that the magnetism stuff has to come from what electrons do. And that’s when I came up with this drawing.” <He shoves a paper napkin at me.> “See, the three balls are electrons and they’re all negative-negative pushing against each other only I’m just paying attention to what the red one’s doing to the other two. Got that?” “Well, that was the puzzle. Here’s a drawing I copied from some book. The magnetic field is those B arrows and there’s three electrons moving in the same flat space in different directions. The red one’s moving along the field and stays that way. The blue one’s moving slanty across the field and gets pushed upwards. The green one’s going at right angles to B and gets bent way up. I’m looking and looking — how come the field forces them to move

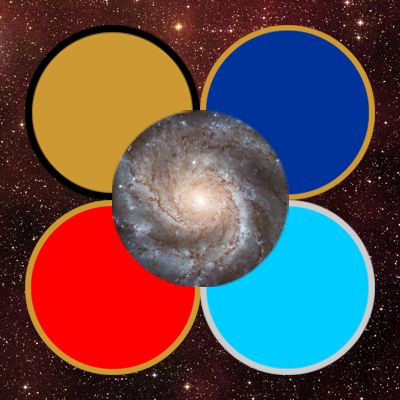

“Well, that was the puzzle. Here’s a drawing I copied from some book. The magnetic field is those B arrows and there’s three electrons moving in the same flat space in different directions. The red one’s moving along the field and stays that way. The blue one’s moving slanty across the field and gets pushed upwards. The green one’s going at right angles to B and gets bent way up. I’m looking and looking — how come the field forces them to move