“TANSTAAFL!” Vinnie’s still unhappy with spacecraft that aren’t rocket-powered. “There Ain’t No Such Thing As A Free Lunch!”

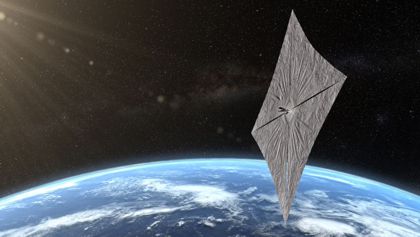

“Ah, good, you’ve read Heinlein. So what’s your problem with Lightsail 2?”

“It can’t work, Sy. Mostly it can’t work. Sails operate fine where there’s air and wind, but there’s none of that in space, just solar wind which if I remember right is just barely not a vacuum.”

Astronomer-in-training Jim speaks up. “You’re right about that, Vinnie. The solar wind’s fast, on the order of a million miles per hour, but it’s only about 10-14 atmospheres. That thin, it’s probably not a significant power source for your sailcraft, Al.”

“I keep telling you folks, it’s not wind-powered, it’s light-powered. There’s oodles of sunlight photons out there!”

“Sure, Al, but photons got zero mass. No mass, no momentum, right?”

Electric (E) field is red

Magnetic (B) field is blue

(Image by Loo Kang Wee and Fu-Kwun Hwang from Wikimedia Commons)

My cue to enter. “Not right, Vinnie. Experimental demonstrations going back more than a century show light exerting pressure. That implies non-zero momentum. On the theory side … you remember when we talked about light waves and the right-hand rule?”

“That was a long time ago, Sy. Remind me.”

“… Ah, I still have the diagram on Old Reliable. See here? The light wave is coming out of the screen and its electric field moves electrons vertically. Meanwhile, the magnetic field perpendicular to the electric field twists moving charges to scoot them along a helical path. So there’s your momentum, in the interaction between the two fields. The wave’s combined action delivers force to whatever it hits, giving it momentum in the wave’s direction of travel. No photons in this picture.”

Astrophysicist-in-training Newt Barnes dives in. “When you think photons and electrons, Vinnie, think Einstein. His Nobel prize was for his explanation of the photoelectric effect. Think about some really high-speed particle flying through space. I’m watching it from Earth and you’re watching it from a spaceship moving along with it so we’ve each got our own frame of reference.”

“Frames, awright! Sy and me, we’ve talked about them a lot. When you say ‘high-speed’ you’re talking near light-speed, right?”

“Of course, because that’s when relativity gets significant. If we each measure the particle’s speed, do we get the same answer?”

“Nope, because you on Earth would see me and the particle moving through compressed space and dilated time so the speed I’d measure would be more than the speed you’d measure.”

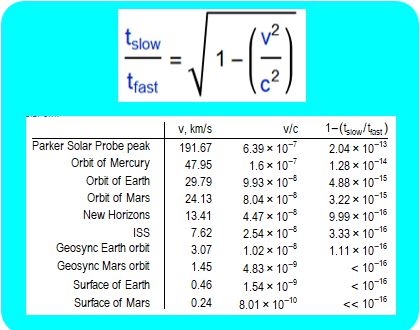

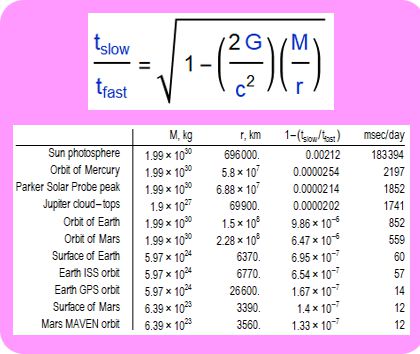

“Mm-hm. And using ENewton=mv² you’d assign it a larger energy than I would. We need a relativistic version of Newton’s formula. Einstein said that rest mass is what it is, independent of the observer’s frame, and we should calculate energy from EEinstein²=(pc)²+(mc²)², where p is the momentum. If the momentum is zero because the velocity is zero, we get the familiar EEinstein=mc² equation.”

“I see where you’re going, Newt. If you got no mass OR energy then you got nothing at all. But if something’s got zero mass but non-zero energy like a photon does, then it’s got to have momentum from p=EEinstein/c.”

“You got it, Vinnie. So either way you look at it, wave or particle, light carries momentum and can power Lightsail 2.”

“Question is, can sunlight give it enough momentum to get anywhere?”

“Now you’re getting quantitative. Sy, start up Old Reliable again.”

“OK, Newt, now what?”

“How much power can Lightsail 2 harvest from the Sun? That’ll be the solar constant in joules per second per square meter, times the sail’s area, 32 square meters, times a 90% efficiency factor.”

“Got it — 39.2 kilojoules per second.”

“That’s the supply, now for the demand. Lightsail 2 masses 5 kilograms and starts at 720 kilometers up. Ask Old Reliable to use the standard circular orbit equations to see how long it would take to harvest enough energy to raise the craft to another orbit 200 kilometers higher.”

“Combining potential and kinetic energies, I get 3.85 megajoules between orbits. That’s only 98 seconds-worth. I’m ignoring atmospheric drag and such, but net-net, Lightsail 2‘s got joules to burn.”

“Case closed, Vinnie.”

~~ Rich Olcott

“Gravitational waves are relativity effects and neutrinos are quantum mechanical. Physicists have been struggling for a century to bridge those two domains. Evidence from a three-messenger event could provide the final clues.”

“Gravitational waves are relativity effects and neutrinos are quantum mechanical. Physicists have been struggling for a century to bridge those two domains. Evidence from a three-messenger event could provide the final clues.”

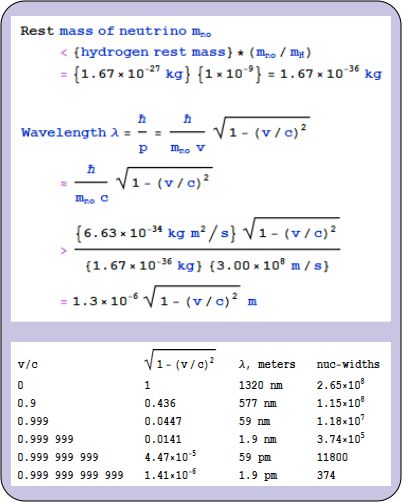

“Half an eV? That’s all? So how come the Big Guy’s got gazillions of eV’s?”

“Half an eV? That’s all? So how come the Big Guy’s got gazillions of eV’s?” “That infinity sign at the bottom means ‘as big as you want.’ So to answer your first question, there isn’t a maximum neutrino energy. To make a more energetic neutrino, just goose it to go even closer to the speed of light.”

“That infinity sign at the bottom means ‘as big as you want.’ So to answer your first question, there isn’t a maximum neutrino energy. To make a more energetic neutrino, just goose it to go even closer to the speed of light.”

“Hello, Jennie. Haven’t seen you for a while.”

“Hello, Jennie. Haven’t seen you for a while.” Momentum is velocity times mass. These guys fly so close to lightspeed that for a long time scientists thought that neutrinos are massless like photons. They’re not, so I used several different v/c ratios to see what the relativistic correction does. Slow neutrinos are huge, by atom standards. Even the fastest ones are hundreds of times wider than a nucleus.”

Momentum is velocity times mass. These guys fly so close to lightspeed that for a long time scientists thought that neutrinos are massless like photons. They’re not, so I used several different v/c ratios to see what the relativistic correction does. Slow neutrinos are huge, by atom standards. Even the fastest ones are hundreds of times wider than a nucleus.”

Cathleen saves me from answering. “Not quite. The study Sy’s chasing is actually a cute variation on red-shift measurements. That ‘PSR‘ designation means the neutron star is a pulsar. Those things emit electromagnetic radiation pulses with astounding precision, generally regular within a few dozen nanoseconds. If we receive slowed-down pulses then the object’s going away; sped-up and it’s approaching, just like with red-shifting. The researchers derived orbital parameters for all three bodies from the between-pulse durations. The heavy dwarf is 200 times further out than the light one, for instance. Not an easy experiment, but it yielded an important result.”

Cathleen saves me from answering. “Not quite. The study Sy’s chasing is actually a cute variation on red-shift measurements. That ‘PSR‘ designation means the neutron star is a pulsar. Those things emit electromagnetic radiation pulses with astounding precision, generally regular within a few dozen nanoseconds. If we receive slowed-down pulses then the object’s going away; sped-up and it’s approaching, just like with red-shifting. The researchers derived orbital parameters for all three bodies from the between-pulse durations. The heavy dwarf is 200 times further out than the light one, for instance. Not an easy experiment, but it yielded an important result.”

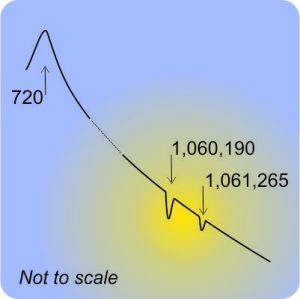

“So you’re telling me, Cathleen, that you can tell how hot a star is by

“So you’re telling me, Cathleen, that you can tell how hot a star is by  Cathleen turns to her laptop and starts tapping keys. “Let’s do an example. Suppose we’re looking at a star’s broadband spectrogram. The blackbody curve peaks at 720 picometers. There’s an absorption doublet with just the right relative intensity profile in the near infra-red at 1,060,190 and 1,061,265 picometers. They’re 1,075 picometers apart. In the lab, the sodium doublet’s split by 597 picometers. If the star’s absorption peaks are indeed the sodium doublet then the spectrum has been stretched by a factor of 1075/597=1.80. Working backward, in the star’s frame its blackbody peak must be at 720/1.80=400 picometers, which corresponds to a temperature of about 6,500 K.”

Cathleen turns to her laptop and starts tapping keys. “Let’s do an example. Suppose we’re looking at a star’s broadband spectrogram. The blackbody curve peaks at 720 picometers. There’s an absorption doublet with just the right relative intensity profile in the near infra-red at 1,060,190 and 1,061,265 picometers. They’re 1,075 picometers apart. In the lab, the sodium doublet’s split by 597 picometers. If the star’s absorption peaks are indeed the sodium doublet then the spectrum has been stretched by a factor of 1075/597=1.80. Working backward, in the star’s frame its blackbody peak must be at 720/1.80=400 picometers, which corresponds to a temperature of about 6,500 K.”