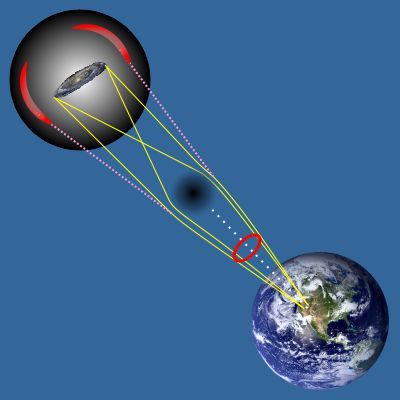

“Hey, Cathleen, if the expansion of the Universe stretches light’s wavelengths, how do you know when you see a color in a star what you’re looking at?”

“Excuse me, Professor, but your office-mate said you’d be here at the coffee shop and I have a homework question.”

“Good heavens, look at the time! It’s my office hours, I should be over there. Oh well, you’re here, Maria, what’s the question?”

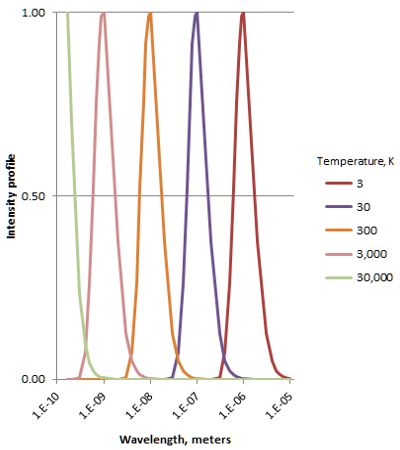

“You showed us this chart and asked us to write an essay on it. I don’t know where to begin.”

“Ah. Hang on, Vinnie, this bears on your question, too. OK, Maria, what can you tell me about the chart?”

“Well, there are five peaked curves, labeled with different temperatures. Can I assume the green curve peaks, too, not continuing straight up?”

“Yes. What else?”

“The horizontal axis, sorry I don’t know the word —”

“abscissa”

“Oh, we have almost the same word in Spanish! Anyhow, the abscisa says it shows wavelengths. It goes from a tenth of a nanometer to maybe 10 micrometers. The chart must have to do with light, because sound waves can’t get that short. The … ordinada…?”

“Ordinate”

“Thank you. The ordinate says ‘Intensity’ so the chart must show light spectra at different temperatures. But there’s only one peak at each temperature.”

“Is that Kirchhoff’s ‘continuous spectrum,’ Cathleen?”

“Right, Vinnie, a smoothly-varying cascade of every wavelength, photons arising from heat-generated motion of charged particles.”

“Ah, ya lo veo — this is blackbody spectra given off by hot objects. You showed us one in class and here we have several.”

“Good, Maria. Now —”

“But all the peaks look exactly the same, Cathleen. The hot objects ought to be brighter. A really hot flame, you can’t even look at it. Something’s phony.”

“Good eye, Vinnie. I divided each curve in the graph by its peak height to put them all on an even footing. That’s why the axis is labeled ‘Intensity profile‘ instead of ‘Intensity.'”

“I’ve got a different issue, Cathleen. Hot objects have more energy to play with. Shouldn’t the hotter peaks spread over a wider wavelength range? These are all the same width.”

“I think I know the answer to that one, Mr Moire. In class la profesora showed us how the blackbody curve’s equation has two factors, like B=W*X. The W factor depends only on wavelength and grows bigger as the wavelength gets smaller. That’s the ‘ultraviolet catastrophe,’ right, ma’am?”

“Mm-hm. Go on, Maria.”

“But the X factor gets small real fast as the wavelength gets small. In fact, it gets small so fast that it overpowers W‘s growth — the W*X product gets small, too. Do you have that movie you showed us on your laptop there, ma’am?”

“Sure. Here it is…”

“OK, the blue line is that W factor. Oh, by the way, the ordinate scale here is logarithmic, so the value at the left end of the blue line is 1027/106 or about 1021 times bigger than it is at the right end even though it looks like a straight line. The green line is that temperature-dependent factor. See how it pulls down the orange lines’ values for cold objects, but practically goes away for very hot objects?”

“Yeah, that shows it real good, right, Sy? That orange peak moves to the left just like Cathleen’s picture shows. It answers your question, too.”

“It does, Vinnie? How so?”

“‘Cause the peaks get broader as they get higher. It’s like the intensity at the, umm, microwave end hardly changes at all and the whole rest of the curve swings up and out from there.”

“Keep in mind, guys, that we’re talking really large numbers here. Vinnie’s ‘hardly changes at all’ is actually a factor of 40,000 or so. Those pretty peaks in my homework chart are only pretty because the spread-out tails are so small relative to the peaks.”

“Alright, Cathleen, but how does Maria’s question tie in with mine?”

“They both hinge on wavelength. The blackbody equation lets us measure a star’s temperature by looking at its color. Do you have enough to start on that essay, Maria?”

“Yes, ma’am. Gracias.”

“De nada. Now run along and get to work on it.”

~~ Rich Olcott

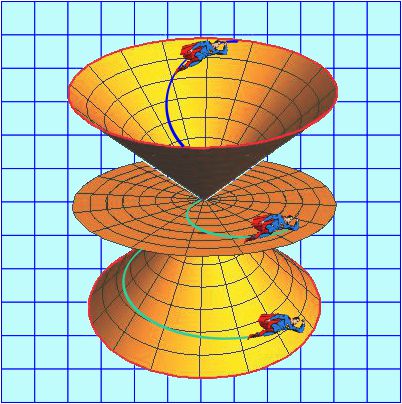

“Whoa, Sy. Do you read the final chapter of a mystery story before you begin the book?”

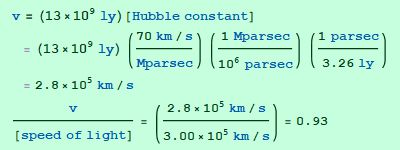

“Whoa, Sy. Do you read the final chapter of a mystery story before you begin the book?” “It is, Sy, and that’s one of the reasons why Hubble’s original number was so far off. He only looked at about 50 close-by galaxies, some of which are moving toward us and some away. You only get a view of the general movement when you look at large numbers of galaxies at long distances. It’s like looking through a window at a snowfall. If you concentrate on individual flakes you often see one flying upward, even though the fall as a whole is downward. Andromeda’s 250,000 mph march towards us is against the general expansion.”

“It is, Sy, and that’s one of the reasons why Hubble’s original number was so far off. He only looked at about 50 close-by galaxies, some of which are moving toward us and some away. You only get a view of the general movement when you look at large numbers of galaxies at long distances. It’s like looking through a window at a snowfall. If you concentrate on individual flakes you often see one flying upward, even though the fall as a whole is downward. Andromeda’s 250,000 mph march towards us is against the general expansion.”

“Infinite?”

“Infinite?”

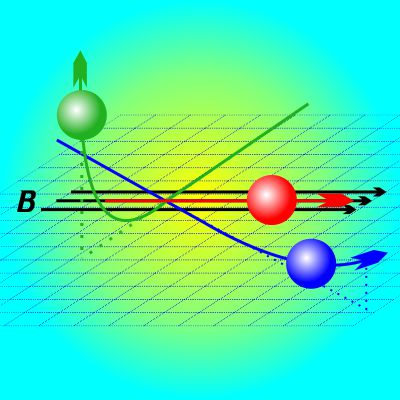

“It told me that the magnetism stuff has to come from what electrons do. And that’s when I came up with this drawing.” <He shoves a paper napkin at me.> “See, the three balls are electrons and they’re all negative-negative pushing against each other only I’m just paying attention to what the red one’s doing to the other two. Got that?”

“It told me that the magnetism stuff has to come from what electrons do. And that’s when I came up with this drawing.” <He shoves a paper napkin at me.> “See, the three balls are electrons and they’re all negative-negative pushing against each other only I’m just paying attention to what the red one’s doing to the other two. Got that?” “Well, that was the puzzle. Here’s a drawing I copied from some book. The magnetic field is those B arrows and there’s three electrons moving in the same flat space in different directions. The red one’s moving along the field and stays that way. The blue one’s moving slanty across the field and gets pushed upwards. The green one’s going at right angles to B and gets bent way up. I’m looking and looking — how come the field forces them to move

“Well, that was the puzzle. Here’s a drawing I copied from some book. The magnetic field is those B arrows and there’s three electrons moving in the same flat space in different directions. The red one’s moving along the field and stays that way. The blue one’s moving slanty across the field and gets pushed upwards. The green one’s going at right angles to B and gets bent way up. I’m looking and looking — how come the field forces them to move

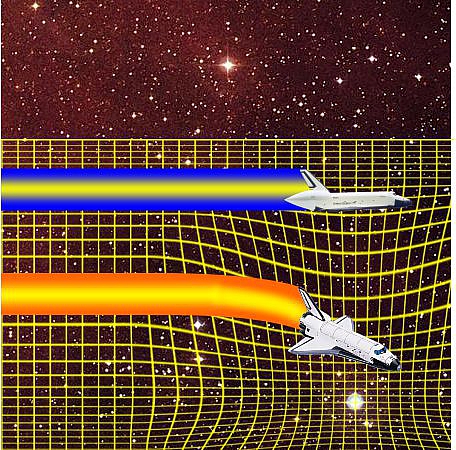

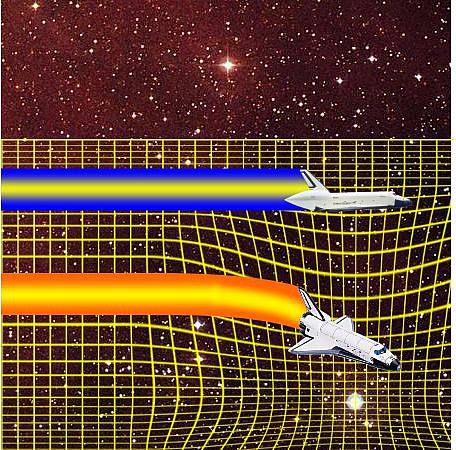

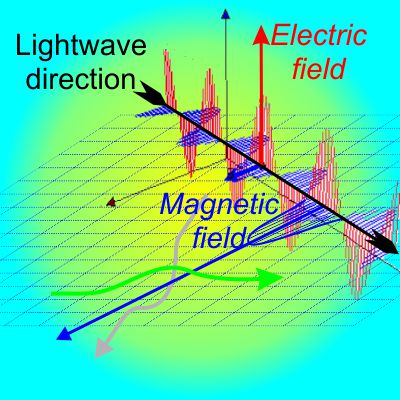

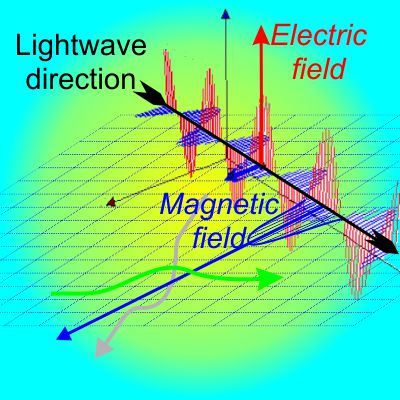

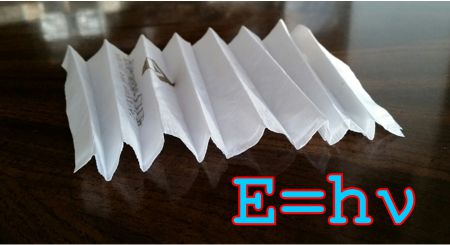

I smoothed out one of Vinnie’s crumpled napkins. As I folded it into pleats and scooted it along the table I said, “Doesn’t mess up the wave so much as change the way we think about it. We’re used to graphing out a spatial wave as an up-and-down pattern like this that moves through time, right?”

I smoothed out one of Vinnie’s crumpled napkins. As I folded it into pleats and scooted it along the table I said, “Doesn’t mess up the wave so much as change the way we think about it. We’re used to graphing out a spatial wave as an up-and-down pattern like this that moves through time, right?”