<shout from outside my office door> “Stromboli Express. Get ’em while they’re hot!”

“The door’s open, Eddie, and you’re right on schedule.”

“I aim to please, Sy. Which ain’t easy while I’m wearing this virus mask.”

“On you it looks good, Eddie. Just leave the order on the credenza. How’s my account?”

“Still good from that last twenty. I gotta say, I appreciate you keeping your tab on the plus side. You, Vinnie, all you singles, your orders are keeping me in business despite that corporate PizzaDoodle shop that opened up.”

“Doing my part to keep the money local, Eddie. Besides, you do good pizza.”

“What difference does keeping the money local make? Anything to do with money being energy?”

“Whoa, where did that come from?”

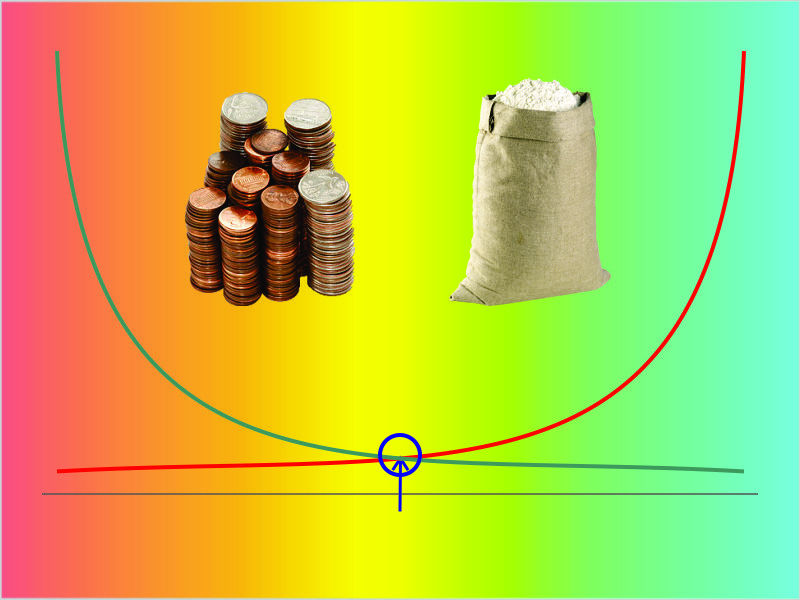

“You told me, Sy. When prices get higher than a perfect supply‑demand market would set them, it’s from inefficiency like what happens to machine energy that gets turned into heat by friction.”

“Ah, you stretched my metaphor a little too far. Money behaves like energy in some ways but not in others. For one thing, Conservation of Energy applies universally, we think, but Conservation of Money not so much.”

“The dollars in my wallet don’t multiply, that’s for sure.”

“Individuals aren’t allowed to fiddle the money supply — that’s called counterfeiting. But the 1930s Great Depression taught us that purposefully creating and destroying money is part of the government’s job. Banks can vary the money supply, too, sort of.”

“Yeah, I’ve seen videos of the Mint’s printing presses and them grinding up ratty old used bills.”

“That’s the least of what they do these days. Depending on which way you define ‘money’, only about a fifth of the money supply is cash currency.”

“There’s definitions of money?”

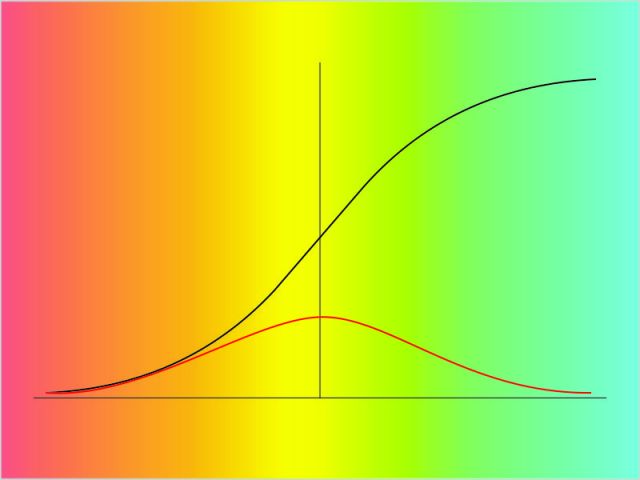

“Mm-hm. That’s one of the keys to the part the banks play. One definition is just the currency, like you’d think. The economists pay attention to a broader definition. When you deposit tonight’s receipts in the bank, the cash doesn’t just sit in a vault. For that matter, your credit card and debit card take can’t sit in a vault. What does the bank do? It keeps a certain percentage of its deposited dollars as a reserve in case you want to pull dollars out to pay Joey for his sausage or something. The rest of those dollars can be loaned out. The loaned dollars generally get deposited for a while before they’re spent and a fraction of those deposits can be loaned out … you see where this is going.”

“Whoa, so I put on a hundred and that turns into maybe four, five hundred or more by when the dust settles. I see what you mean about banks creating money even if it’s not real money.”

“Oh, it’s real money — officially blessed marks in a ledger or more likely, bits in computers instead of paper and coins, but it counts. Anyhow, the second definition of ‘money’ combines currency and deposits from all those loans.”

“So what’s to prevent the bank from loaning out all their money and riding this pony over and over again? That’s what I’d want to do, pull in interest on like, infinite loans.”

“That’s where the government steps in. Depositors need to be sure they can make withdrawals. The Feds don’t tell banks, ‘You can only loan out a certain number of dollars.‘ What they do say is, “Your reserves have to total up to at least x fraction of your deposits.’ The Feds are free to change the value of x up or down depending on whether they want to shrink or expand the money supply.”

“Closing down or opening up the spigot and Conservation of Money ain’t a thing, gotcha. But what does that have to do with you guys keeping money local?”

“Think back to that $20 bill that went from you to Vinnie to Al to me to you. What would have happened if Al had decided to invest in some weird coffee beans instead of buying those magazines from me?”

“The dollars would fly away from our local bank and they wouldn’t be there for an x fraction loan for my business. Gotcha.”

~~ Rich Olcott