Change-me Charlie’s not giving up easily. “You said that NASA picture did three things, but you only told us two of them — that dark matter’s a thing and that it’s separate from normal matter. What’s the third thing? What exactly is in that picture? Does it tell us what dark matter is?”

Physicist-in-training Newt’s ready for him. “Not much of a clue about what dark matter is, but a good clue about how it behaves. As to what’s in the picture, we need some background information first.”

“Go ahead, it’s not dinner-time yet.”

“First, this isn’t two stars colliding. It’s not even two galaxies. It’s two clusters of galaxies, about 40 all together. The big one on the left probably has the mass of a couple quintillion Suns, the small one about 10% of that.”

“That’s a lot of stars.”

“Oh, most of it’s definitely not stars. Maybe only 1-2%. Those stars and the galaxies they form are embedded in ginormous clouds of proton-electron plasma that make up 5-20% of the mass. The rest is that dark matter you don’t like.”

“Quadrillions of stars are gonna make a super-super-nova when they collide!”

“Well, no. That doesn’t even happen when two galaxies collide. The average distance between neighboring stars in a galaxy is 200-300 times the diameter of a star so it’s unlikely that any two of them will come even close. Next level up, the average distance between galaxies in a cluster is about 60 galaxy diameters or more, depending. The galaxies will mostly just slide past each other. The real colliders are the spread-out stuff — the plasma clouds and of course the dark matter, whatever that is.”

Astronomer-in-training Jim cuts in. “Anyway, the collision has already happened. The light from this configuration took 3.7 billion years to reach us. The collision itself was longer ago than that because the bullet’s already passed through the big guy. From that scale-bar in the bottom corner I’d say the centers are about 2 parsecs apart. If I recall right, their relative velocity is about 3000 kilometers per second so…” <poking at his smartphone> “…the peak intersection was about 700 million years earlier than that. Call it 4.3 billion years ago.”

“So what’s with the cotton candy?”

Newt looks puzzled. “Cotton… oh, the pink pixels. They’re markers for where NASA’s Chandra telescope saw X-rays coming from.”

“What can make X-rays so far from star radiation that could set them going?”

“The electrons do it themselves. An electron emits radiation every time it collides with another charged particle and changes direction. When two plasma clouds interpenetrate you get twice as many particles per unit volume and four times the collision rate so the radiation intensity quadruples. There’s always some X-radiation in the plasma because the temperature in there is about 8400 K and particle collisions are really violent. The Chandra signal pink shows the excess over background.”

“The blue in the Jim’s picture is supposed to be what, extra gravity?”

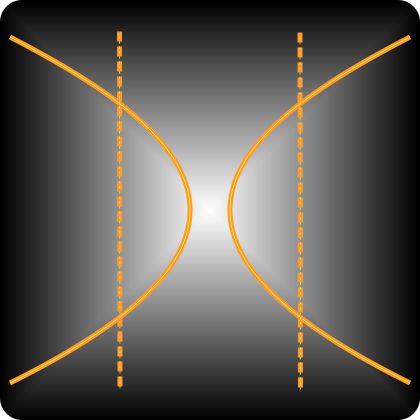

“Basically, yeah. It’s not easy to see from the figure, but there are systematic distortions in the images of the background galaxies in the blue areas. Disks and ellipsoids appear to be bent, depending on where they sit relative to the clusters’ centers of mass. The researchers used Einstein’s equations and lots of computer time to work back from the distortions to the lensing mass distributions.”

“So what we’ve got is a mostly-not-from-stars gravity lump to the left, another one to the right, and a big cloud in the middle with high-density hot bits on its two sides. Something in the middle blew up and spread gas around mostly in the direction of those two clusters. What’s that tell us?”

“Sorry, that’s not what happened. If there’d been a central explosion the excess to the right would be arc-shaped, not a cone like you see. No, this really is the record of one galaxy cluster bursting through another one. Particle-particle friction within the plasma clouds held them back while the embedded galaxies and dark matter moved on.”

“OK, the galaxies aren’t close-set enough for them to slow each other down, but wouldn’t friction in the dark matter hold things back, too?”

“Now that’s an interesting question…”

~~ Rich Olcott

~~ Rich Olcott

~~ Rich Olcott

“Thanks, Sy. Look, we’ve got three intervals where everything syncs up. See the new satellite peaks half-way in between? There’s more hidden pattern where things look chaotic in the rest of the space.”

“Thanks, Sy. Look, we’ve got three intervals where everything syncs up. See the new satellite peaks half-way in between? There’s more hidden pattern where things look chaotic in the rest of the space.”