“Sy, it’s nice that Einstein agreed with Rayleigh’s wave theory stuff but why’d you even drag him in? I thought the faster‑than‑light thing was settled.”

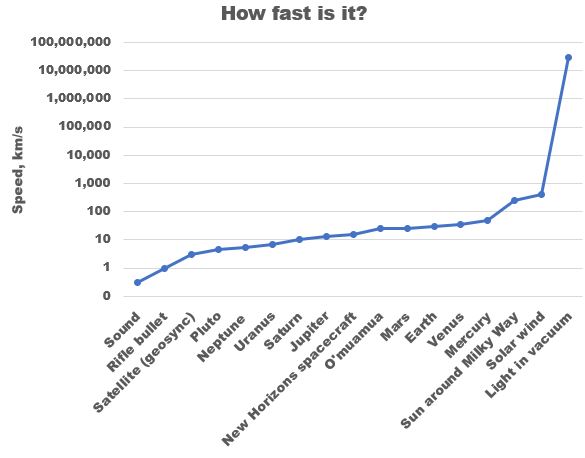

“Vinnie, faster‑than‑light wasn’t even an issue until Einstein came along. Science had known lightspeed was fast but not infinite since Rømer measured it in Newton’s day. ‘Pretty fast,’ they said, but Newtonian mechanics is perfectly happy with any speed you like. Then along came Einstein.”

“Speed cop, was he?”

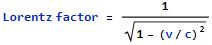

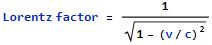

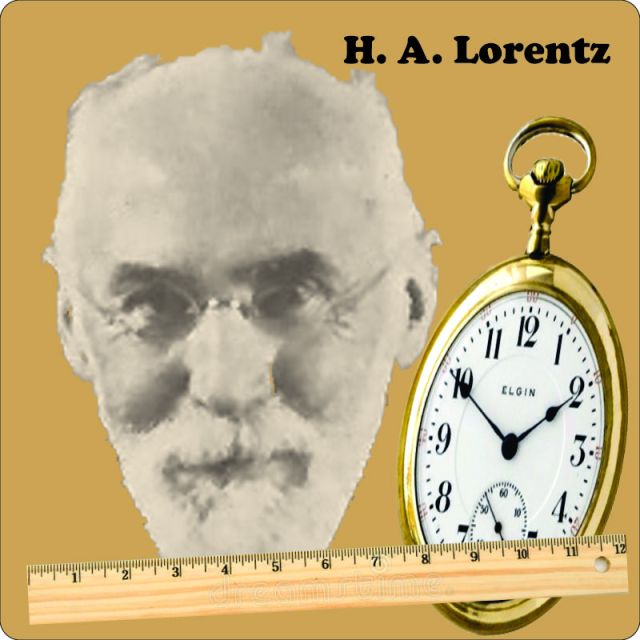

“Funny, Vinnie. No, Einstein showed that the Universe enforces the lightspeed limit. It’s central to how the Universe works. Come to think of it, the crucial equation had been around for two decades, but it took Einstein to recognize its significance.”

“Ah, geez, equations again.”

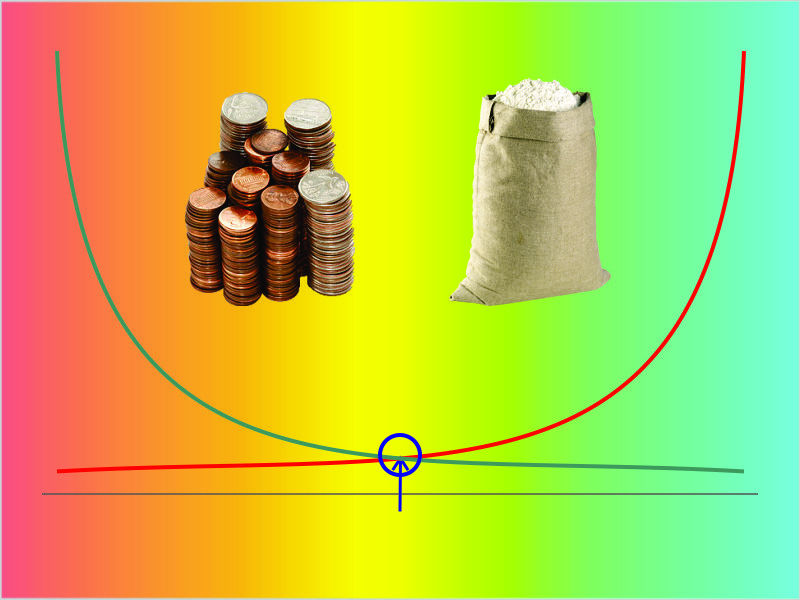

“Just this one and it’s simple. It’s all about comparing v for velocity which is how fast something’s going, to c the speed of light. Nothing mystical about the arithmetic — if you’re going half the speed of light, the factor works out to 1.16. Ninety‑nine percent of c gives you 7.09. Tack on another 9 and you’re up to 22.37 and so on.”

“You got those numbers memorized?”

“Mm-hm, they come in handy sometimes.”

“Handy how? What earthly use is it? Nothing around here goes near that fast.”

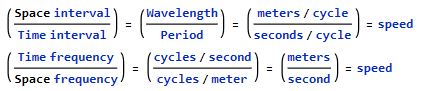

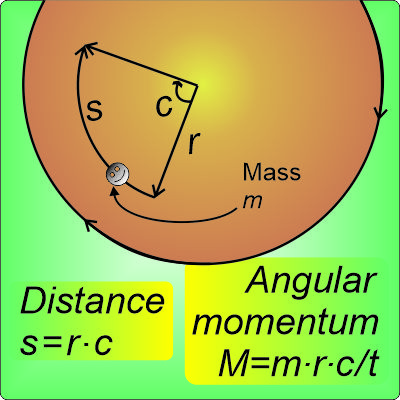

“Do you like your GPS? It’d be useless if the Lorentz factor weren’t included in the calculations. The satellites that send us their sync signals have an orbit about 84 000 kilometers wide. They run that circle once a sidereal day, just shy of 86 400 seconds. That works out to 3 kilometers per second and a Lorentz factor of 1.000 005.”

“Yeah, so? That’s pretty close to 1.0.”

“It’s off by 5 parts per million. Five parts per million of Earth’s 25 000-mile circumference is an eighth of a mile. Would you be happy if your GPS directed you to somewhere a block away from your address?”

“Depends on why I’m going there, but I get your point. So where else does this factor come into play?”

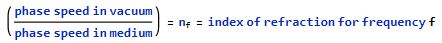

“Practically anywhere that involves a precision measurement of length or duration. It’s at the core of Einstein’s Special Relativity work. He thought about observing a distant moving object. It’s carrying a clock and a ruler pointed along the direction of motion. The observer would see ticks of the clock get further apart by the Lorentz factor, that’s time dilation. Meanwhile, they’d see the ruler shrink by the factor’s inverse, that’s space compression.”

“What’s this ‘distant observer‘ business?”

“It’s less to do with distance than with inertial frames. If you’re riding one inertial frame with a GPS satellite, you and your clock stay nicely synchronized with the satellite’s signals. You’d measure its 1×1‑meter solar array as a perfect square. Suppose I’m riding a spaceship that’s coasting to Mars. I measure everything relative to my own inertial frame which is different from yours. With my telescope I’d measure your satellite’s solar array as a rectangle, not a square. The side perpendicular to the satellite’s orbit would register the expected 1 meter high, but the side pointing along the orbit would be shorter, 1 meter divided by the Lorentz factor for our velocity difference. Also, our clocks would drift apart by that Lorentz factor.”

“Wait, Sy, there’s something funny about that equation.”

“Oh? What’s funny?”

“What if somebody’s speed gets to c? That’d make the bottom part zero. They didn’t let us do that in school.”

“And they shouldn’t — the answer is infinity. Einstein spotted the same issue but to him it was a feature, not a bug. Take mass, for instance. When they meet Einstein’s famous E=mc² equation most people think of the nuclear energy coming from a stationary lump of uranium. Newton’s F=ma defined mass in terms of a body’s inertia — the greater the mass, the more force needed to achieve a certain amount of acceleration. Einstein recognized that his equation’s ‘E‘ should include energy of motion, the ½mv² kind. He had to adjust ‘m‘ to keep F=ma working properly. The adjustment was to replace inertial mass with ‘relativistic mass,’ calculated as inertial mass times the Lorentz factor. It’d take infinite force to accelerate any relativistic mass up to c. That’s why lightspeed’s the speed limit.”

~~ Rich Olcott