(the coffee-shop saga continues) “Wait on, Sy, a black hole is a hollow sphere?”

I hadn’t noticed her arrival but there was Jennie, standing by Vinnie’s table and eyeing Jeremy who was sill eyeing Anne in her white satin. “That’s not quite what I said, Jennie. Old Reliable’s software and and I worked up a hollow-shell model and to my surprise it’s consistent with one of Stephen Hawking’s results. That’s a long way from saying that’s what a black hole is.”

“That’s not quite what I said, Jennie. Old Reliable’s software and and I worked up a hollow-shell model and to my surprise it’s consistent with one of Stephen Hawking’s results. That’s a long way from saying that’s what a black hole is.”

“But you said some physicists say that. Have they aught to stand on?”

“Sort of. It’s a perfect case of ‘depends on where you’re standing.'”

Vinnie looked up. “It’s frames again, ain’t it?”

“With black holes it’s always frames, Vinnie. Hey, Jeremy, is a black hole something you could stand on?”

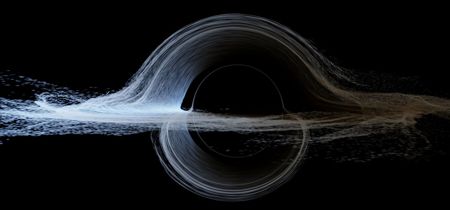

“Nosir, we said the hole’s event horizon is like Earth’s orbit, just a mathematical marker. Except for the gravity and the three Perils Jennie and you and me talked about, I’d slide right through without feeling anything weird, right?”

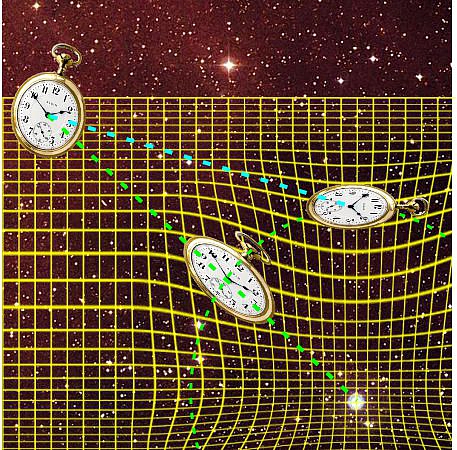

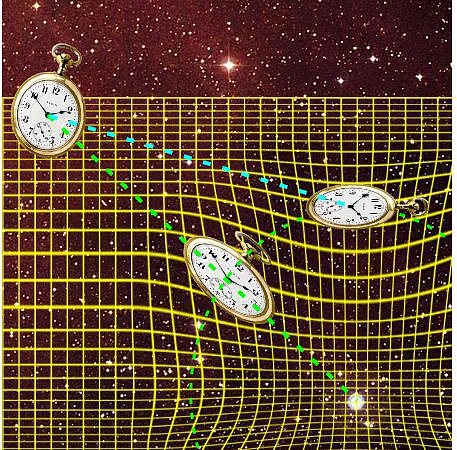

“Good memory and just so. In your frame of reference there’s nothing special about that surface — you wouldn’t experience scale changes in space or time when you encounter it. In other frames, though, it’s special. Suppose we’re standing a thousand miles away from a solar-size black hole and Jeremy throws a clock and a yardstick into it. What would we see?”

“This is where those space compression and time dilation effects happen, innit?”

“You bet, Jennie. Do you remember the formula?”

“I wrote it in my daybook … Ah, here it is — My notes say D is the black hole’s diameter and d is another object’s distance from its center. One second in the falling object’s frame would look like f seconds to us. But one mile would look like 1/f miles. The event horizon is where d equals the half-diameter and f goes infinite. The formula only works where the object stays outside the horizon.”

My notes say D is the black hole’s diameter and d is another object’s distance from its center. One second in the falling object’s frame would look like f seconds to us. But one mile would look like 1/f miles. The event horizon is where d equals the half-diameter and f goes infinite. The formula only works where the object stays outside the horizon.”

“And as your clock approaches the horizon, Jeremy…?”

“You’ll see my clock go slower and slower until it sto —. Oh. Oh! That’s why those physicists think all the infalling mass is at the horizon, the stuff falls towards it forever and never makes it through.”

“Exactly.”

“Hey, waitaminute! If all that mass never gets inside, how’d the black hole get started in the first place?”

“That’s why it’s only some physicists, Vinnie. The rest don’t think we understand the formation process well enough to make guesses in public.”

“Wait, that formula’s crazy, Sy. If something ever does get to where d is less than D/2, then what’s inside the square root becomes negative. A clock would show imaginary time and a yardstick would go imaginary, too. What’s that about?”

“Good eye, Anne, but no worries, the derivation of that formula explicitly assumes a weak gravitational field. That’s not what we’ve got inside or even close to the event horizon.”

“Mmm, OK, but I want to get back to the entropy elephant. Does black hole entropy have any connection to the other kinds?”

“Strutural, mostly. The numbers certainly don’t play well together. Here’s an example I ran up recently on Old Reliable. Say we’ve got a black hole twice the mass of the Sun, and it’s at the Hawking temperature for its mass, 12 billionths of a Kelvin. Just for grins, let’s say it’s made of solid hydrogen. Old Reliable calculated two entropies for that thing, one based on classical thermodynamics and the other based on the Bekenstein-Hawking formulation.” “Wow, Old Reliable looks up stuff and takes care of unit conversions automatically?”

“Wow, Old Reliable looks up stuff and takes care of unit conversions automatically?”

“Slick, eh, Jeremy? That calculation up top for Schem is classical chemical thermodynamics. A pure sample of any element at absolute zero temperature is defined to have zero entropy. Chemical entropy is cumulative heat capacity as the sample warms up. The Hawking temperature is so close to zero I could treat heat capacity as a constant.

“In the middle section I calculated the object’s surface area in square Planck-lengths lP², and in the bottom section I used Hawking’s formula to convert area to B-H entropy, SBH. They disagree by a factor of 1033.”

A moment of shocked silence, and then…

~~ Rich Olcott

, where D is the object’s diameter and d is your distance from it. Suppose the Sun suddenly collapsed without losing any mass to become a Schwarzchild object. The object’s diameter would be a bit less than 4 miles. Earth is 93 million miles from the Sun so the compression factor here would be [poking numbers into my smartphone] 1.000_000_04. Nothing you’d notice. It’d be 1.000_000_10 at Mercury. You wouldn’t see even 1% compression until you got as close as 378 miles, 10% only inside of 43 miles. Fifty percent of the effect shows up in the last 13 miles. The edge of a black hole is sharper than this pizza knife.”

, where D is the object’s diameter and d is your distance from it. Suppose the Sun suddenly collapsed without losing any mass to become a Schwarzchild object. The object’s diameter would be a bit less than 4 miles. Earth is 93 million miles from the Sun so the compression factor here would be [poking numbers into my smartphone] 1.000_000_04. Nothing you’d notice. It’d be 1.000_000_10 at Mercury. You wouldn’t see even 1% compression until you got as close as 378 miles, 10% only inside of 43 miles. Fifty percent of the effect shows up in the last 13 miles. The edge of a black hole is sharper than this pizza knife.”

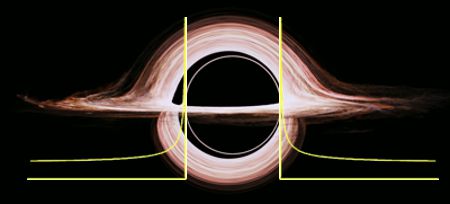

. A is proportional to spin. When A is small (not much spin) or the distance is large those A/d² terms essentially vanish relative to the others and the scaling looks just like the simple almost-a-point Schwarzchild case. When A is large or the distance is small the A/d² terms dominate top and bottom, the factor equals 1 and there’s dragging but no compression. In the middle, things get interesting and that’s where Dr Thorne played.”

. A is proportional to spin. When A is small (not much spin) or the distance is large those A/d² terms essentially vanish relative to the others and the scaling looks just like the simple almost-a-point Schwarzchild case. When A is large or the distance is small the A/d² terms dominate top and bottom, the factor equals 1 and there’s dragging but no compression. In the middle, things get interesting and that’s where Dr Thorne played.”

“OK,

“OK,

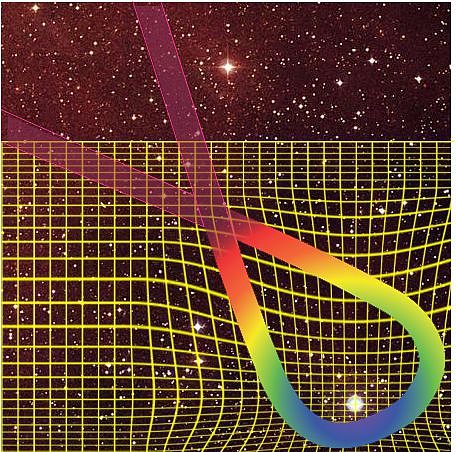

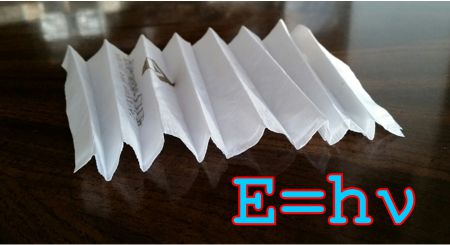

I smoothed out one of Vinnie’s crumpled napkins. As I folded it into pleats and scooted it along the table I said, “Doesn’t mess up the wave so much as change the way we think about it. We’re used to graphing out a spatial wave as an up-and-down pattern like this that moves through time, right?”

I smoothed out one of Vinnie’s crumpled napkins. As I folded it into pleats and scooted it along the table I said, “Doesn’t mess up the wave so much as change the way we think about it. We’re used to graphing out a spatial wave as an up-and-down pattern like this that moves through time, right?”