“Gee, Mr Moire, if Einstein and Friedmann are right, some day the Universe will expand exponentially and everything dies. Even Dr Mack says that’s a downer.”

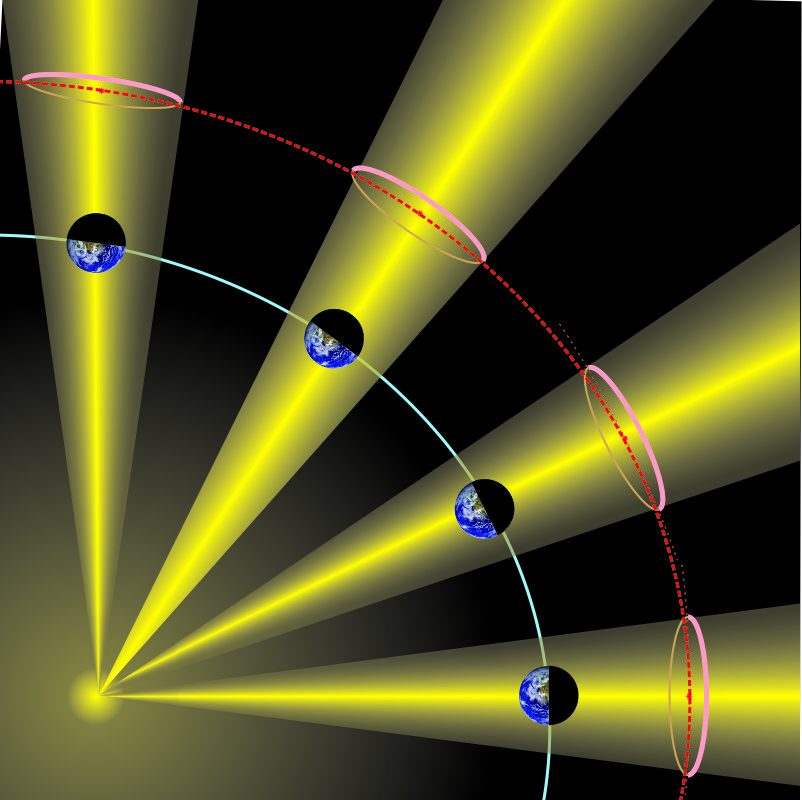

“First, it’s not ‘some day,’ it’s already. We’ve got evidence that exponential expansion became the dominant process five billion years ago. The interesting questions are about what happens during the expansion and what the timeline will be. That’s all controlled by a single weird parameter so naturally the parameter’s conventional symbol is w. Each major component of the Universe has its own value of w and they combine to predict the future course of the Universe.”

“Weird sounds like fun. What is it, another difference like the Cosmological Constant minus that mass‑pressure stuff?”

“Good guess, but it’s not a difference, It’s a ratio, between different flavors of energy.”

“Kinetic and potential, I’ll bet.”

“That split seems to be a common theme in Physics, doesn’t it? In this case, you’re almost right if we stretch things. One of the energy flavors is mass, including both normal and dark matter. If you take the long view, every atom of normal matter will sooner or later break down so you can think of it as a packet of potential energy, pent up and waiting for release. Dark matter, who knows? Anyway, w‘s denominator is mass per unit volume. The numerator’s a little trickier. As you guessed, we need something related to kinetic energy and we slide into that sideways.”

“How so?”

“Well, most of the normal matter is very dilute hydrogen which we can treat like a perfect gas. That’s something we’ve got a good theory for. Per unit volume, gas particle kinetic energy is proportional to pressure and that’s what we use for w‘s numerator. Averaged over the volume of space the pressure‑to‑mass ratio w for matter moving at ordinary speeds is effectively zero.”

“Does dark matter follow the same formula?”

“We pretend it does.”

“How about photons? They don’t have mass so that ratio would be infinity.”

“True, but they do carry momentum and it turns out w is simply ⅓ for photons and neutrinos and anything else traveling at relativistic speeds. Then there’s the Cosmological Constant’s w, which is minus‑one. Since the Big Bang we’ve gone from radiation‑dominated to matter‑dominated to Constant‑dominated; the effective w has shifted from somewhat positive to zero and into negative territory. Thanks to the surviving photons and matter, though, we’re still at least slightly above –1.0.”

“What difference does that make?”

“Minus‑one is the boundary between fates for the Universe. More positive than that, gravity and electromagnetism are guaranteed to be stronger than dark energy. Expansion will move gravity‑bound objects farther away from each other, but the galaxies and each galaxy cluster will stay together. The supply of hydrogen that fuels new stars will peter out. Eventually all the stars will gutter out and disappear into the cold dark as they wait for their constituent atoms to decay. The whole process will take something like 1010¹⁰ years.”

“That’s dark, alright, but at least it’ll take a long time. What happens of w is more negative than minus‑one?”

“The Big Rip. If w is more negative than the threshold, dark energy will grow stronger with time. We don’t know of anything that would limit the growth. First dark energy overpowers gravity and allows the galaxies and stars to disperse. Then it overrides the electromagnetism that holds molecules and rocks together. Eventually even the weak and strong nuclear forces will be defeated — no more atoms. Depending on how extreme w is, figure something like 200 billion years, give or take an eon.”

“Wow. But wait, we’ve covered radiation and mass and the Constant and none of them have a w below the threshold. What can have a more negative w?”

“A hypothesis. If there is anything, pretty much all we have is a name, ‘phantom energy,’ which is even more tentative than ‘dark energy.’ People are working to evaluate w with data. Results so far are so close to –1.0 that we can’t tell if it’s above or below the threshold or just teetering on the brink.”

“Two hundred billion years or way more. No worries, hey?”

~~ Rich Olcott

Jeremy Yazzie @jeremyaz

Jeremy Yazzie @jeremyaz Sy Moire @symoire

Sy Moire @symoire Hi, Sy, can you believe this weather? Temps last week were twice today’s high.

Hi, Sy, can you believe this weather? Temps last week were twice today’s high.