A darkish day calls for a fresh scone so I head for Al’s coffee shop. Cathleen’s there with some of her Astronomy students. Al’s at their table instead of his usual place behind the cash register. “So what’s going on with these FRBs?”

She plays it cool. “Which FRBs, Al? Fixed Rate Bonds? Failure Review Boards? Flexible Reed Baskets?”

Jim, next to her, joins in. “Feedback Reverb Buffers? Forged Razor Blades?

Fennel Root Beer?”

I give it a shot. “Freely Rolling Boulders? Flashing Rapiers and Broadswords? Fragile Reality Boundary?”

“C’mon, guys. Fast Radio Bursts. Somebody said they’re the hottest thing in Astronomy.”

Cathleen, ever the teacher, gives in. “Well, they’re right, Al. We’ve only known about them since 2007 and they’re among the most mystifying objects we’ve found out there. Apparently they’re scattered randomly in galaxies all over the sky. They release immense amounts of energy in incredibly short periods of time.”

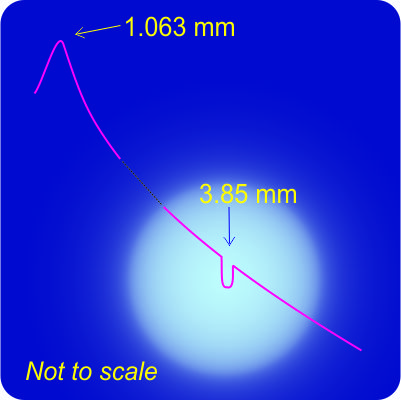

“I’ll say.” Vinnie’s joins the conversation from the next table. “Sy and me, we been talking about using the speed of light to measure stuff. When I read that those radio blasts from somewhere last just a millisecond or so, I thought, ‘Whatever makes that blast happen, the signal to keep it going can’t travel above lightspeed. From one side to the other must be closer than light can travel in a millisecond. That’s only 186 miles. We got asteroids bigger than that!'”

“300 kilometers in metric.” Jim’s back in. “I’ve played with that idea, too. The 70 FRBs reported so far all lasted about a millisecond within a factor of 3 either way — maybe that’s telling us something. The fastest way to get lots of energy is a matter-antimatter annihilation that completely converts mass to energy by E=mc². Antimatter’s awfully rare 13 billion years after the Big Bang, but suppose there’s still a half-kilogram pebble out there a couple galaxies away and it hits a hunk of normal matter. The annihilation destroys a full kilogram; the energy release is 1017 joules. If the event takes one millisecond that’s 1020 watts of power.”

“How’s that stand up against the power we receive in an FRB signal, Jim?”

“That’s the thing, Sy, we don’t have a good handle on distances. We know how much power our antennas picked up, but power reception drops as the square of the source distance and we don’t know how far away these things are. If your distance estimate is off by a factor of 10 your estimate of emitted power is wrong by a factor of 100.”

“Ballpark us.”

<sigh> “For a conservative estimate, say that next-nearest-neighbor galaxy is something like 1021 kilometers away. When the signal finally hits us those watts have been spread over a 1021-kilometer sphere. Its area is something like 1049 square meters so the signal’s power density would be around 10-29 watts per square meter. I know what you’re going to ask, Cathleen. Assuming the radio-telescope observations used a one-gigahertz bandwidth, the 0.3-to-30-Jansky signals they’ve recorded are about a million million times stronger than my pebble can account for. Further-away collisions would give even smaller signals.”

Looking around at her students, “Good self-checking, Jim, but for the sake of argument, guys, what other evidence do we have to rule out Jim’s hypothesis? Greg?”

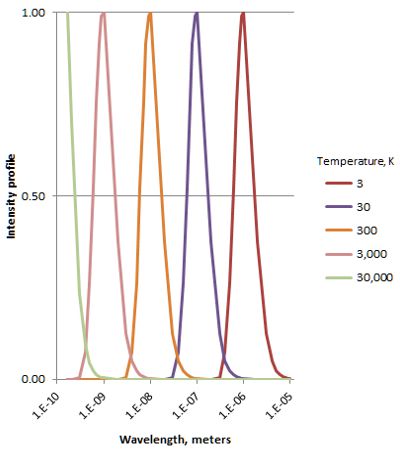

“Mmm… spectra? A collision like Jim described ought to shine all across the spectrum, from radio on up through gamma rays. But we don’t seem to get any of that.”

“Terry, if the object’s very far away wouldn’t its shorter wavelengths be red-shifted by the Hubble Flow?”

“Sure, but the furthest-away one we’ve tagged so far is nearer than z=0.2. Wavelengths have been stretched by 20% or less. Blue light would shift down to green or yellow at most.”

“Fran?”

“We ought to get even bigger flashes from antimatter rocks and asteroids. But all the signals have about the same strength within a factor of 100.”

“I got an evidence.”

“Yes, Vinnie?”

“That collision wouldn’t’a had a chance to get started. First contact, blooie! the gases and radiation and stuff push the rest of the pieces apart and kill the yield. That’s one of the problems the A-bomb guys had to solve.”

Al’s been eaves-dropping, of course. “Hey, guys. Fresh Raisin Bread, on the house.”

~~ Rich Olcott

“Hello, Jennie. Haven’t seen you for a while.”

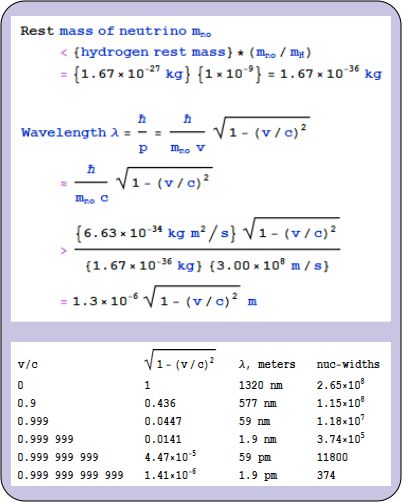

“Hello, Jennie. Haven’t seen you for a while.” Momentum is velocity times mass. These guys fly so close to lightspeed that for a long time scientists thought that neutrinos are massless like photons. They’re not, so I used several different v/c ratios to see what the relativistic correction does. Slow neutrinos are huge, by atom standards. Even the fastest ones are hundreds of times wider than a nucleus.”

Momentum is velocity times mass. These guys fly so close to lightspeed that for a long time scientists thought that neutrinos are massless like photons. They’re not, so I used several different v/c ratios to see what the relativistic correction does. Slow neutrinos are huge, by atom standards. Even the fastest ones are hundreds of times wider than a nucleus.”

Cathleen saves me from answering. “Not quite. The study Sy’s chasing is actually a cute variation on red-shift measurements. That ‘PSR‘ designation means the neutron star is a pulsar. Those things emit electromagnetic radiation pulses with astounding precision, generally regular within a few dozen nanoseconds. If we receive slowed-down pulses then the object’s going away; sped-up and it’s approaching, just like with red-shifting. The researchers derived orbital parameters for all three bodies from the between-pulse durations. The heavy dwarf is 200 times further out than the light one, for instance. Not an easy experiment, but it yielded an important result.”

Cathleen saves me from answering. “Not quite. The study Sy’s chasing is actually a cute variation on red-shift measurements. That ‘PSR‘ designation means the neutron star is a pulsar. Those things emit electromagnetic radiation pulses with astounding precision, generally regular within a few dozen nanoseconds. If we receive slowed-down pulses then the object’s going away; sped-up and it’s approaching, just like with red-shifting. The researchers derived orbital parameters for all three bodies from the between-pulse durations. The heavy dwarf is 200 times further out than the light one, for instance. Not an easy experiment, but it yielded an important result.”