“How’re we gonna tell, Mr Moire?”

“Tell what, Jeremy?”

“Those two expanding Universe scenarios. How do we find out whether it’s gonna be the Big Rip or the Big Chill?”

“The Solar System will be recycled long before we’d have firm evidence either way. The weak dark energy we have now is most effective at separating things that are already at a distance. In the Big Rip’s script a brawnier dark energy would show itself first by loosening the gravitational bonds at the largest scale. Galaxies would begin scattering into the voids between the multi‑galactic sheets and filaments we’ve been mapping. Only later would the galaxies themselves release their stars to wander off and dissolve when dark energy gets strong enough to overcome electromagnetism.”

“How soon will we see those things happen?”

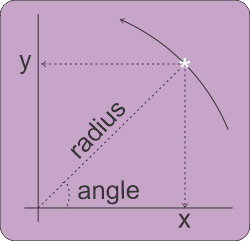

“If they happen. Plan on 188 billion years or so, depending on how fast dark energy strengthens. The Rip itself would take about 2 billion years, start to finish. Remember, our Sun will go nova in only five billion years so even the Rip scenario is far, far future. I prefer the slower Chill story where the Cosmological Constant stays constant or at least the w parameter stays on the positive side of minus‑one. Weak dark energy doesn’t mess with large gravitationally‑bound structures. It simply pushes them apart. One by one galaxies and galaxy clusters will disappear beyond the Hubble horizon until our galaxy is the only one in sight. I take comfort in the fact that our observations so far put w so close to minus‑one that we can’t tell if it’s above or below.”

“Why’s that?”

“The closer (w+1) approaches zero, the longer the timeline before we’re alone. We’ll have more time for our stars to complete their life cycles and give rise to new generations of stars.”

“New generations of stars? Wow. Oh, that’s what you meant when you said our Solar System would be recycled.”

“Mm-hm. Think about it. Back when atoms first coalesced after the Big Bang, they were all either hydrogen or helium with just a smidgeon of lithium for flavor. Where did all the other elements come from? Friedmann’s student George Gamow figured that out, along with lots of other stuff. Fascinating guy, interested in just about everything and good at much of it. Born in Odessa USSR, he and his wife tried twice to defect to the West by kayak. They finally made it in 1933 by leveraging his invitation to Brussels and the Solvay Conference on Physics where Einstein and Bohr had their second big debate. By that time Gamow had produced his ‘liquid drop‘ theory of how heavy atomic nuclei decay by spitting out alpha particles and electrons. He built on that theory to explain how stars serve as breeder reactors.”

“I thought breeder reactors are for turning uranium into plutonium for bombs. Did he have anything to do with that?”

“By the start of the war he was a US citizen as well as a top-flight nuclear theorist but they kept him away from the Manhattan Project. That undoubtedly was because of his Soviet background. During the war years he taught university physics, consulted for the Navy, and thought about how stars work. His atom decay work showed that alpha particles could escape from a nucleus by a process a little like water molecules in a droplet bypassing the droplet’s surface tension. For atoms deep inside the Sun, he suggested that his droplet process could work in reverse. He calculated the temperatures and pressures it would take for gravity to force alpha particles or electrons into different kinds of nuclei. The amazing thing was, his calculations worked.”

“Wait — alpha particles? Where’d they come from if the early stars were just hydrogen and helium?”

“An alpha particle is just a helium atom with the electrons stripped off. Anyway, with Gamow leading the way astrophysicists figured out how much of which elements a given star would create by the time it went nova. Those elements became part of the gas‑dust mix that coalesces to become the next generation of stars. We may have gone through 100 such cycles so far.”

“A hundred generations of stars. Wow.”

~~ Rich Olcott