<chirp, chirp> “Moire, here, there’ll be a late-night surcharge for this call.”

“Hiya, Sy, it’s me, Vinnie. Got a minute? I wanna run something past you.”

“Sure, if it’s interesting enough to keep me awake.”

“It’s that Physics-money hobby horse you’ve been riding. I think I’ve got another angle on it for you.”

“Really? Shoot.”

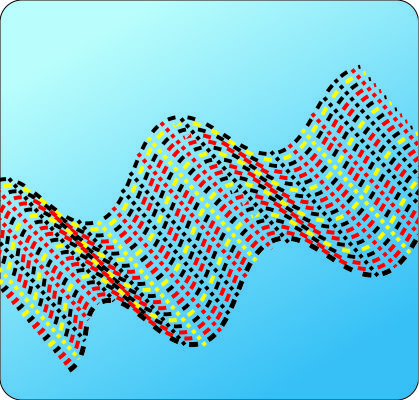

“OK, a while ago you and me and Richard Feder talked about waves and how light waves and sound waves are different because light waves make things go up-and-down while the waves go forward but sound waves go back-and-forth.”

“Transverse waves versus compression waves, uh-huh.”

“Yeah and when you look close at a sound wave what you see is individual molecules don’t travel. What happens is like in a pool game where one ball bumps another ball and it stops but the bumped ball moves forward and the first ball maybe even moves back a little.”

“The compression momentum carries forward even though the particles don’t, right.”

“And that means that sound waves only travel as fast as the air molecules can move back and forth which is a lot slower than light waves which move by shaking the electric field. I got that, but why doesn’t sound move a lot faster in something like iron where the atoms don’t have to move?”

“Oh, it does, something like 200 times faster than in air. There’s a couple of factors in play. It all goes back to Newton —”

“Geez, he had a hand in everything Physics, didn’t he?”

“Except for electromagnetism and nuclear stuff. The available technology was just too primitive to let him experiment in those areas. Anyway, Newton discovered a formula connecting the speed of sound in a medium to its density. Like his Law of Gravity, it worked but he didn’t know why it worked. Also like gravity, we’ve got a better idea now.”

“What’s the better idea?”

“The key notions weren’t even invented until decades after Newton’s Principia was published. The magic words are the particulate nature of matter and intermolecular stiffness.”

“Hah?”

“One at a time. Newton was a particle guy to an extent. He believed that light is made of particles, but he didn’t take the next step to thinking of all matter as being made of particles. But it is, and the particles interact with each other. Think of it as stickiness. How effective the stickiness is depends on the temperature and which molecules you’re talking about. Gas molecules have so much kinetic energy relative to their sticky that they mostly just bounce off each other. In liquids and solids the molecules stay close enough together that the stickiness acts like springs. The springs may be more or less stiff depending on which molecules or ions or atoms are involved.”

“I see where you’re going. Stuff with stiffer springs doesn’t move as much as looser stuff at the same temperature; sound goes faster through a solid than through a liquid or gas. That’s what Newton figured out, huh?”

“No, he just measured and said, basically, ‘here’s the formula.‘ Just like with gravity, he didn’t suggest why the numbers were what they were. <yawn> So, you called with an idea about sound and money physics.”

“Right. Got off the track there, but this was helpful. What got me started was some newscaster saying how the Paycheck Protection Program is dumping money into the economy during the pandemic. My first thought was, ‘Haw, that’s gotta be a splash!‘ Then I imagined this pulse of money sloshing back and forth like a wave and that led me to sound waves and then I kept going. No dollar bill moves around that much, but when people spend them that’s like the compression wave moving out.”

“Interesting idea, Vinnie. From a Physics perspective, the question is, ‘How fast does the wave move?’ It’s another temperature‑versus‑stickiness thing.”

“Yeah, I figure money velocity measures the economy like temperature measures molecule motion. Money velocity goes up with inflation. If the velocity’s high people spend their money because why not.”

“Yup. From the government’s perspective the whole purpose of economic stimulation is getting the cash flowing again. Their problem is locating the money velocity kickover point.”

~~ Rich Olcott