“All that cloud stuff goes on in Jupiter’s tissue-paper outer layer. What’s the rest of the planet doing, Cathleen?”

“You’re not going to like this, Vinnie, but all we’ve got so far is broad‑brush averages. The Galileo atmosphere probe penetrated less than 0.2% of the way to the center. The good news is that the Juno probe has been sending us oodles of data about Jupiter’s gravity and magnetic fields. That’s great for planet‑wide theorizing, not quite as useful for weather prediction.”

“Can the data explain the Great Red Spot?”

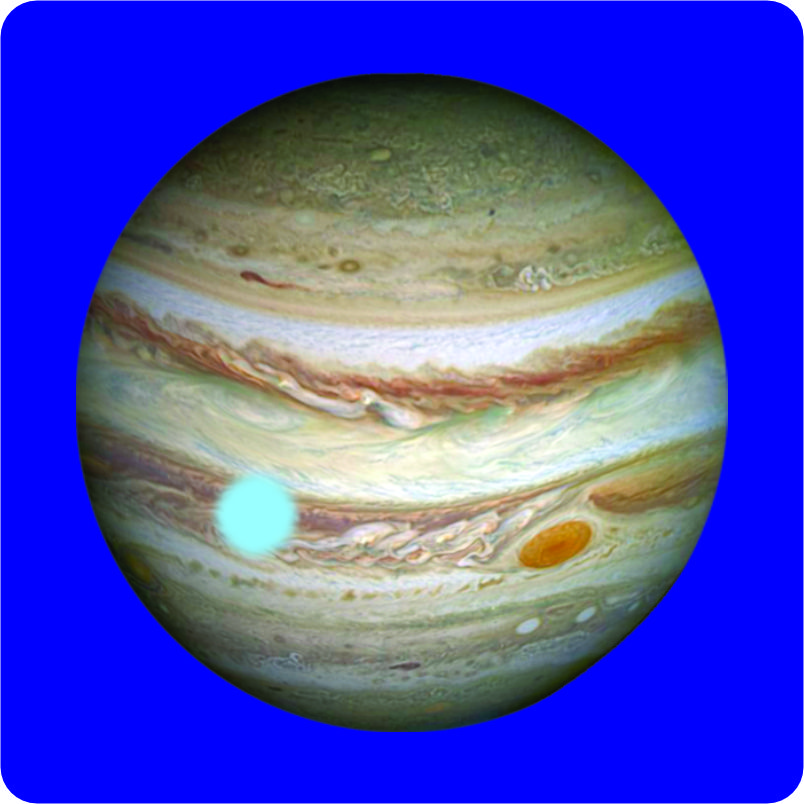

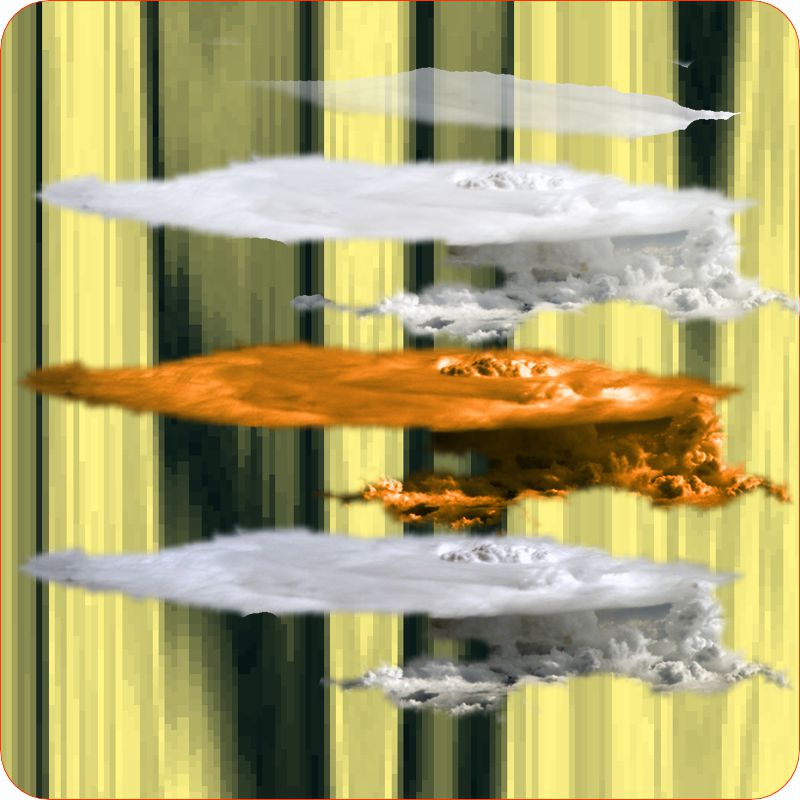

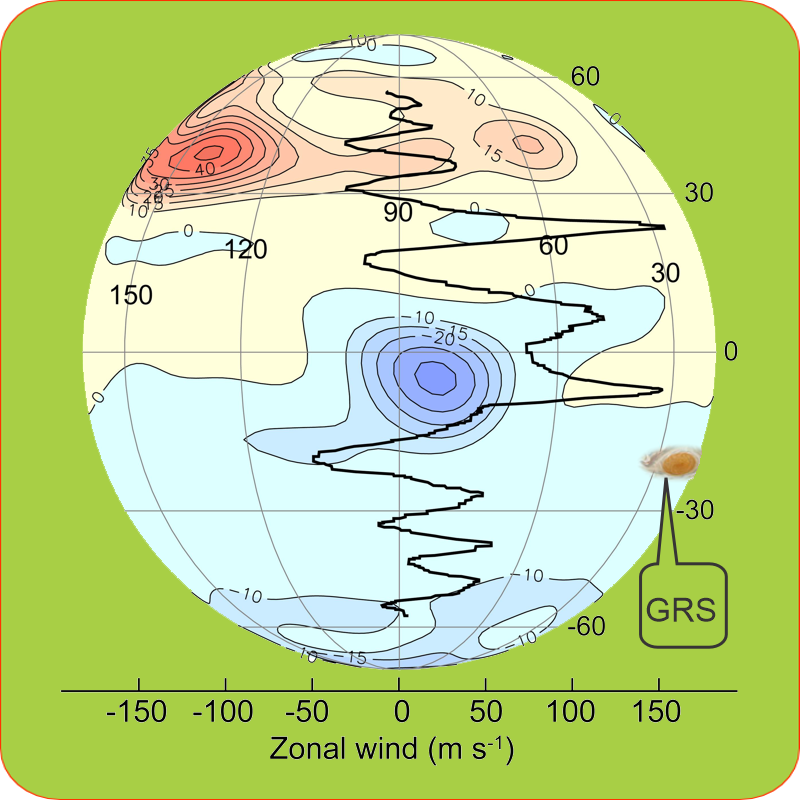

“Well, it ruled out some ideas. Back in the day we thought the Spot was a deep whirlpool opening a view into the interior. Nope. Juno‘s measurements revealed that the Spot is actually a dome rising hundreds of kilometers above the white cloud‑tops. When one window closes, another one opens, I suppose. The fact that the Spot’s a dome says down below there’s an immense energy source lifting the gases above it. We don’t know what it is or why it’s there or how for two centuries it’s mostly held position in a completely fluid environment.”

“Weird. You’d expect something like that at a special location, like at one of the poles, but the Spot isn’t even on the planet’s equator.”

“Right, Sy. Its latitude is 22° south.”

“Hey, that’s the Tropic of Capricorn.”

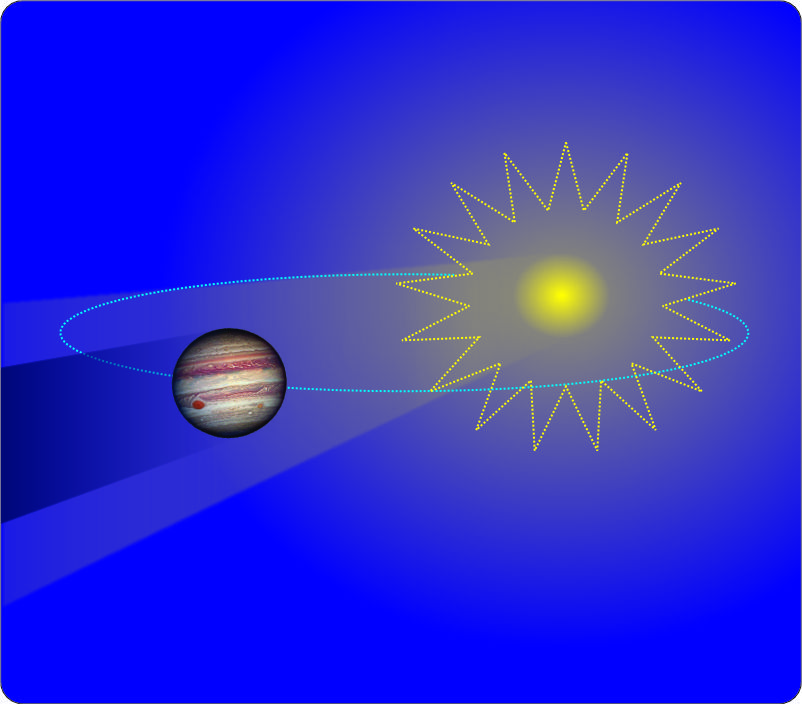

“Almost, Vinnie, but not relevant. Earth’s two Tropics are at 23½° north and south. If the Earth’s rotational axis were perpendicular to its solar orbit, the Sun’s highest position would always be directly over the Equator. But Earth’s axis is tilted at 23½° to our orbital plane. To see the noon Sun at the zenith you’d have to be 23½° north of the Equator in June, 23½° south of the Equator in December. Jupiter’s rotational axis is tilted, too, but by only 3°. That rules out significant seasonality on Jupiter, but it also says that on Jupiter there’s nothing special about 22° except that it’s where the Spot hangs out.”

“How about longitude?”

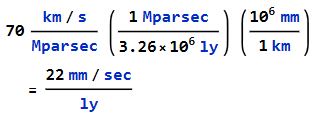

“Longitude on Jupiter is an embarrassing topic. Zero longitude on Earth, our Prime Meridian, runs through Greenwich Observatory in London, right? I don’t want to get into the history behind that. On a completely gaseous planet like Jupiter, there’s no stable physical object to tag with a zero. Jupiter’s cloud‑tops rotate faster near its equator than at its poles. Neither rotation syncs with Jupiter’s magnetic field which is like Earth’s except it’s much more intense and it points in the opposite direction. Oh, and it’s offset from the center of the planet and it’s lumpy. For lack of a better alternative, astronomers arbitrarily thumbtacked Jupiter’s Prime Meridian to its magnetic field. They selected the magnetic longitudinal line that pointed directly towards Earth at a particular moment in 1965. Given a good clock and the field’s rate of rotation you can calculate where that line will be at any other time.”

“Sounds like that ephemeris strategy Sy told me about in our elevator adventure. Why’s that embarrassing?”

“Well, back in 1965 the tool of choice for studying Jupiter’s rotating magnetic field was radio spectroscopy. Technology wasn’t as good as we have now and they … didn’t get a completely accurate rate of rotation. We’re stuck with a standard coordinate system where the Prime Meridian slips about 3° every year relative to the magnetic field. Even the Great Red Spot slips a little.”

“Cathleen, I’ve read that Juno uncovered a region of particularly intense magnetic activity they’re calling Jupiter’s Great Blue Spot. Does it have any connection to the Red Spot?”

“Probably not, Sy, the Red Spot’s 15° south and 60° east of the Blue. But with Jupiter who knows?”

“Got any other interesting averages?”

“Extreme wind speeds. There’s a jet stream between each pair of Jupiter’s stripes, eastbound on the poleward side of a white zone, westbound in the other side. Look at the zig‑zag graph on this chart. 75 meters/second is 167 miles per hour is a Category 5 hurricane here on Earth. At latitudes near Jupiter’s equator average winds are double that.”

~~ Rich Olcott