A new face in the scone line at Al’s coffee shop. “Morning. I’m Sy Moire, free-lance physicist and Al’s steadiest customer. And you’re…?”

“Robert Tobanu, newest Computer Science post-doc on Dr Hanneken’s team. He needed some help improving the performance of their program suite.”

“Can’t he just buy a faster computer?”

“He could if there is a faster computer, if his grant could afford its price tag, and if it’s faster in the way he needs to solve our problems. My job is to squeeze the most out of what we’ve got on the floor.”

“I didn’t realize that different kinds of problem need different kinds of computer. I just see ratings in terms of mega-somethings per second and that’s it.”

“Horse racing.”

“Beg pardon?”

“Horse speed-ratings come from which horse wins the race. Do you bet on the one with the strongest muscles? The one with the fastest out-of-the-box time? The best endurance? How about Odin’s fabulous eight-legged horse?”

“Any of the above, I suppose, except for the eight-legged one. What’s this got to do with computers?”

“Actually, eight-legged Sleipnir is the most interesting example. But my point is, just saying ‘This is a 38-mph horse‘ leaves a lot of variables up for discussion. It doesn’t tell you how much better the horse would do with a more-skilled jockey. It doesn’t say how much worse the horse would do pulling a racing sulky or a fully-loaded Conestoga. And then there’s the dash-versus-marathon aspect.”

“I’m thinking about Odin’s horse — power from doubled-up legs would be a big positive in a pulling contest, but you’d think they’d just get in the jockey’s way during a quarter-mile dash.”

“Absolutely. All of that’s why I think computer speed ratings belong in marketing brochures, not in engineering papers. ‘MIPS‘ is supposed to mean ‘Millions of Instructions Per Second‘ but it’s actually closer to ‘Misleading Indication of Processor Speed.'”

“How do they get those ratings in the first place? Surely no-one sat there and actually counted instructions as the thing was running.”

“Of course not. Well, mostly not. Everything’s in comparison to an ancient base-case system that everyone agreed to rate at 1.0 MIPS. There’s a collection of benchmark programs you’re supposed to run under ‘standard‘ conditions. A system that runs that benchmark in one-tenth the base-case time is rated at 10 MIPS and so on.”

“I heard voice-quotes around ‘standard.’ Conditions aren’t standard?”

“No more than racing conditions are ever standard. Sunny or wet weather, short-track, long-track, steeplechase, turf, dirt, plastic, full-card or two-horse pair-up — for every condition there are horses well-suited to it and many that aren’t. Same thing for benchmarks and computer systems.”

“That many different kinds of computers? I thought ‘CPU‘ was it.”

“Hardly. With horses it’s ‘muscle, bone and sinew.’ With computers it’s ‘processor, storage and network.’ In many cases network makes or breaks the numbers.”

“Network? Yeah, I got a lot faster internet response when I switched from phone-line to cable, but that didn’t make any difference to things like sorting or computation that run just within my system.”

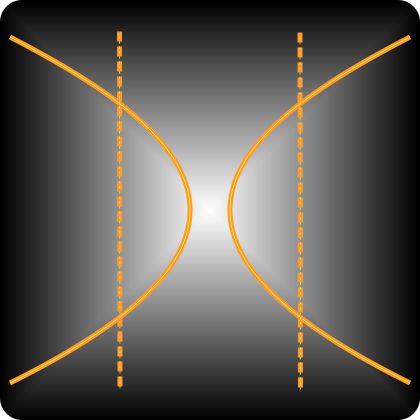

“Sure, the external network impacts your upload and download performance, but I’m talking about the internal network that transports data between your memories and your processors. If transport’s not fast enough you’re wasting cycles. Four decades ago when the Cray-1’s 12.5-nanosecond cycle time was the fastest thing afloat, the company bragged that it had no wire more than a meter long, Guess why.”

“Does speed-of-light play into it?”

“Well hit. Lightspeed in vacuum is 0.3 meters per nanosecond. Along a copper wire it’s about 2/3 of that, so a signal takes about 5 nanoseconds each way to traverse a meter-long wire. Meanwhile, the machine’s working away at 12.5 nanoseconds per cycle. If it’s lucky and there’s no delay at the other end, the processor burns a whole cycle between making a memory request and getting the bits it asked for. Designers have invented all sorts of tricks to get those channels as short as possible.”

“OK, I get that the internal network’s important. Now, about that eight-legged horse…”

~~ Rich Olcott

- Thanks to Richard Meeks for asking an instigating question.