“What’s all the hubbub in the back room, Al? I’m a little early for my afternoon coffee break and your shop’s usually pretty quiet about now.”

“It’s Cathleen’s Astronomy class, Sy. The department double-booked their seminar room so she asked to use my space until it’s straightened out.”

“Think I’ll eavesdrop.” I slide in just as she’s getting started.

“OK, folks, settle. Last class I challenged you with a question. Venus and Mars both have atmospheres that are dominated by carbon dioxide with a little bit of nitrogen. Earth is right in between them. How come its atmosphere is so different? I gave each of you a piece of that to research. Jeremy, you had the null question. Should we expect Earth’s atmosphere to be about the same as the other two?”

JAXA / ISAS / DARTS / Damia Bouic

“I think so, ma’am, on the basis of the protosolar nebula hypothesis. The –“

“Wait a minute, Jeremy. Sy, I saw you sneak in. Jeremy, explain that term to him.”

“Yes’m. Uh, a nebula is a cloud of gas and dust out in space. It could be what got shot out of an exploding star or it could be just a twist in a stream of stuff drifting through the Galaxy. If the twist kinks up, gravity pulls the material on either side of the kink towards the middle and you get a rotating disk. Most of what’s in the disk falls towards its center. The accumulated mass at the center lights up to be a star. Meanwhile, what’s left in the disk keeps most of the original angular momentum but it doesn’t whirl smoothly. There’s going to be local vortices and they attract more stuff and grow up to be planets. That’s what we think happens, anyway.”

“Good summary. So what does that mean for Mars, Venus and the Earth?”

“Their orbits are pretty close together, relative to the disk’s radius, so they ought to have encountered about the same mixture of heavy particles and light ones while they were getting up to size. The light ones would be gas atoms, mostly hydrogen and helium. Half the other atoms are oxygen and they’d react to produce oxides — water, carbon monoxide, grains of silica and iron oxide. And oxygen and nitrogen molecules, of course.”

“Of course. Was gravity the only actor in play there?”

“No-o-o, once the star lit up its photons and solar wind would have pushed against gravity.”

“So three actors. Would photons and solar wind have the same effect? Anybody?”

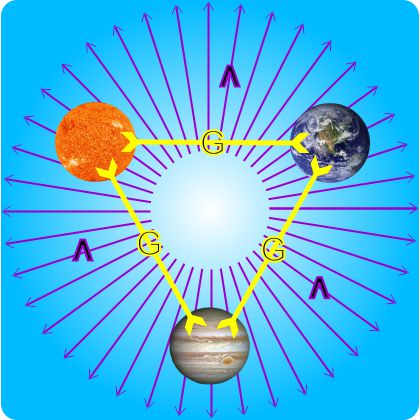

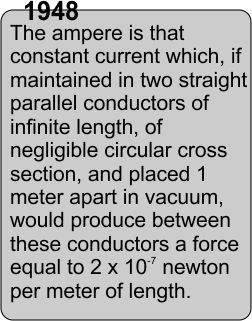

Silence, until astrophysicist-in-training Newt Barnes speaks up. “No, they’d have different effects. The solar wind is heavy artillery — electrons, protons, alpha particles. They’ll transfer momentum to anything they hit, but they’re more likely to hit a large particle like a dust grain than a small one like an atom. On average, the big particles would be pushed away more.”

“And the photons?”

“A photon is selective — it can only transfer momentum to an atom or molecule that can absorb exactly the photon’s energy. But each kind of atom has its own set of emission and absorption energies. Most light emitted by transitions within hydrogen atoms won’t be absorbed by anything but another hydrogen atom. Same thing for helium. The Sun’s virtually all hydrogen and helium. The photons they emit would move just those disk atoms and leave the heavier stuff in place.”

“That’s only part of the photon story.”

“Oh? Oh, yeah. The Sun’s continuous spectrum. The Sun is hot. Heat jiggles whole ions. Those moving charges produce electromagnetic waves just like charge moving within an atom, but heat-generated waves can have any wavelength and interact with anything. They can bake dust particles and decompose compounds that contain volatile atoms. Then those atoms get swept away in the general rush.”

“Which has the greater effect, solar wind or photons?”

“Hard to say without doing the numbers, but I’d bet on the photons. The metal-and-silicate terrestrial planets are close to the Sun, but the mostly-hydrogen giants are further out.”

“All that said, Jeremy, what’s your conclusion?”

“It sure looks like Earth’s atmosphere should be intermediate between Mars and Venus. How come it’s not?”

~~ Rich Olcott